On View

‘I Would Imagine Some Little Child Like Me’: The Eternal Youth of Yoshitomo Nara

His newest exhibition, on view at the Guggenheim Bilbao, is the most significant survey of the artist in Europe to date.

Some people never quite grow up. When I interview Yoshitomo Nara ahead of his mid-career survey at the Guggenheim Bilbao, the 64-year-old artist is dressed like the quintessential Avril-Lavigne-inspired skater boy: hair tousled beneath a black baseball cap, skull-and-crossbones T-shirt, and baggy jeans. This air of youthfulness is in keeping with his art practice. Yoshitomo is perhaps best known for his depictions of children, who invariably feature in his paintings, drawings, sculptures, and installations in cartoonish yet eerie depictions.

An early work like Make the Road, Follow the Road (1990), for example, which is the first work visitors to the Bilbao exhibition encounter, depicts a girl brandishing a knife and flame at a cat who smiles while standing in a puddle of blood. The words “Nothing ever happens, nothing happens at all,” taken from a song by the band Del Amitri, are inscribed in a trail of scarlet smoke. When read in conjunction with the painting’s title, this speaks to the responsibility of carving out one’s own life, and the destructiveness born of boredom.

Yoshitomo Nara, Make the Road, Follow the Road (1990). Collection Aomori Museum of Art

© Yoshitomo Nara, courtesy Yoshitomo Nara Foundation.

Yoshitomo grew up in the Aomori Prefecture of Japan, a quiet, rural, apple-growing region in the northern part of the country’s main island of Honshu. The artist believes that “my predilection for child figures stems from memories of my own childhood.” Other motifs such as red-roofed houses, puddles, and blue boats, which recur throughout his oeuvre also stem from long-held recollections. While Yoshitomo didn’t have access to the cultural vibrancy of Japan’s big cities, and rarely visited art museums or galleries, he tells me: “While [my life] may have objectively looked like loneliness, I was very happy with all of my surroundings—I will always really appreciate this environment because it’s original to me.”

It’s perhaps no coincidence that Yoshitomo has integrated so many references to pop culture and music into his work, given that this was how he connected with the world beyond his countryside idyll. When he was still a child, Yoshitomo constructed a radio that connected with the radio waves of the United States Air Force, which was based in Japan at that time of the Vietnam War. Yoshitomo listened to folk songs by Bob Dylan, and was also later strongly influenced by both the punk and new wave movements.

“When I was in my room, surrounded by apple fields in the 1960s, the wave of music could send me far away,” he said. “I would imagine some little child like me in South America, listening to the same music in a small village.”

Placed in the center of one room in the Guggenheim Bilbao, the installation My Drawing Room (2008), a tiny house-like structure that recreates Yoshitomo’s studio space, emits a playlist of songs that the artist began listening to when he was young, reflecting his enduring love of music. Visitors can even listen to this on Spotify in their own time.

Yoshitomo Nara, My Drawing Room (2008). Collection of the Artist © Yoshitomo Nara, Courtesy Yoshitomo Nara Foundation.

After graduating from Aichi Prefectural University of the Arts in 1987, a year later the young artist moved to Germany to study at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf under the professorship of the German Neo-Expressionist A. R. Penck, a course that took six years. Incorporating looser brushstrokes and more vibrant colors into his paintings was Yoshitomo’s way of responding to Penck’s comment that he was “so free in drawing, but very formal in painting: why don’t you paint like you draw?” Yoshitomo looks at me emphatically when saying: “I learned freedom from Penck.”

Nara was subsequently picked up by Galerie d’Eendt in Amsterdam, receiving his first solo show there in 1990. Just five years later, his exhibition “Pacific Babies” was mounted at Blum and Poe’s Santa Monica gallery in 1995, after which his commercial and institutional profile steadily grew. The exhibition at Guggenheim Bilbao is the most significant survey dedicated to the artist in Europe to date. It will later travel to Baden-Baden’s Frieder Burda Museum and the Hayward Gallery in London.

The exhibition is curated broadly chronologically, though not strictly, with pairings from different decades also punctuating the show. The paintings from the late 1980s and early 1990s are galvanizing in their use of rough layered brushstrokes and thick outlines, drawn with relaxed swiftness. Take Give You the Flower (1990), for example, in which two figures float in a messy white-and-pink surround. A mermaid angel sweats profusely while offering a flower to a smiling girl who flaunts a knife. At once saccharine, tense, and surreal, the bold dynamism of Yoshitomo’s imagination in such works peters out as the show progresses, with significantly later paintings such as Midnight Tears (2023) marred with sentimentalism. A wide-eyed child spills heavy tears over pale skin, their dark hair comprising patches of color that—as the wall texts insist—demonstrate Yoshitomo’s knowledge of the European masters, deconstructing color with “energized pointillism.”

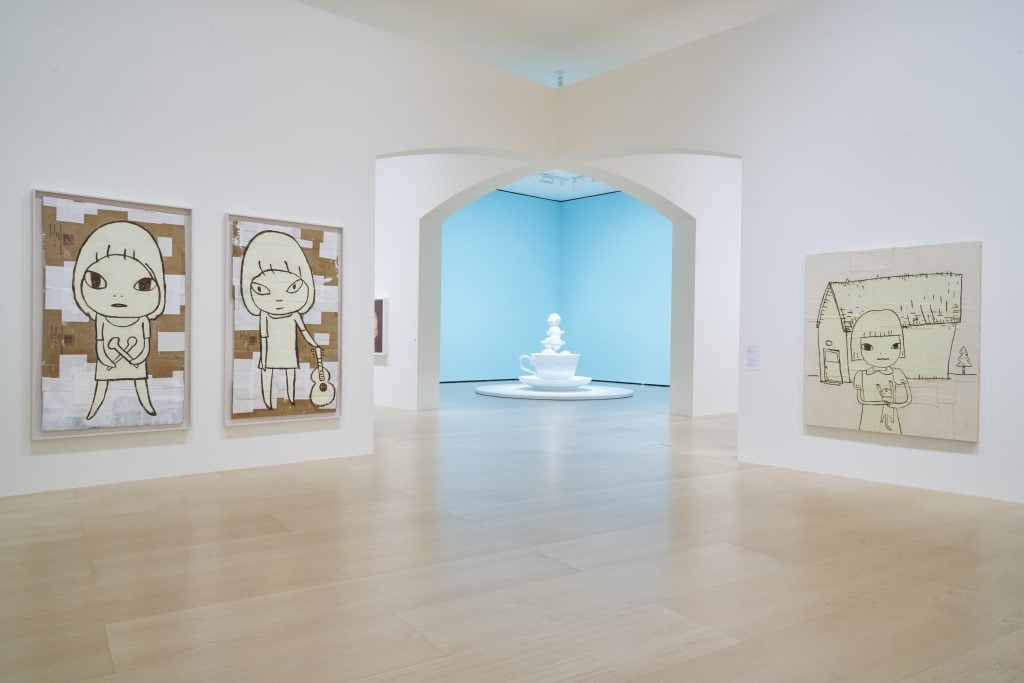

Installation view of “Yositomo Nara” at Guggenheim Bilbao. Courtesy of Guggenheim Bilbao.

In fact, I would argue that drawing has continued to be Yoshitomo’s modus operandi, demonstrating immediacy, verve, and spirit. As such, the curatorial decision to hang numerous works on cardboard and paper without wall labels is an error, decreasing the importance of these pieces and incorrectly rendering them subsidiary in Yoshitomo’s oeuvre.

One of the exhibition’s standout drawings is a cruciform piece of card onto which a sloppy ground of white is sketched; thick black marker pen is used to draw a girl with a blank expression, pointing a gun alongside block text that reads, “I am Right wing, I am Left wing!” It captures the furor of this moment, in which populism and nationalism are on the rise amid divisive politics. Yoshitomo tells me, “Japan is an isolated country, but Korea and China are getting stronger. Japanese people have so many fears about becoming weak, that’s why they are becoming more like right-wing.”

A shrewd survey exhibition of Yoshitomo’s drawings from 1988–2023 was mounted by Pace Gallery at their Geneva outpost last year—not that Yoshitomo’s market needs any bolstering. In October 2019, the artist set the auction record for the most expensive work by a Japanese pop artist, with Knife Behind Back (2000) selling at Sotheby’s in Hong Kong for HK$195,696,000 (£20,229,095), while on May 26, 2022, Wish World Peace (2014) exceeded its lowest presale estimate of £8.9 million by realizing £9.8 million at Christie’s 20th/21st Century Art Evening Sale in Hong Kong.

Yoshitomo Nara’s record-setting work Knife Behind Back (2000). Courtesy Sotheby’s Hong Kong.

Many of the loans for the Guggenheim Bilbao exhibition came from private collectors, as well as institutions in Japan and Korea, and a number were enabled via Pace Gallery and Blum Gallery. When it comes to the sale of his work, Yoshitomo is notably quiet and has become notorious for sidestepping questions about the market. When I press him on why this is, he replies, “After a while, there were people who bought my work for investment purposes… When I first understood what the mechanism of the art world is—not the artist world, but the art market—I just didn’t really want to be there anymore… The act of painting itself hasn’t really changed, but I started to be suspicious about the galleries, the collectors.”

As opposed to his market success, Yoshitomo says he is truly motivated by the same sense of connection that inspired him as a child when listening to the radio. He imagines his friend’s children being enthused by the work. Having returned to live in the north of Japan in 2000, the artist is drawn to anonymity, and “wants to see people who don’t really know who I am.”

Yoshitomo stresses that he was his most fulfilled in the early 1990s when he was a student. And while his propensity towards sentimentalism creeps in again towards the end of our conversation, I can’t help but soften at Yoshitomo’s concluding words regarding that chapter of his life: he says, “I gained something that I couldn’t buy with the money: experience. I found a treasure in myself, and I never want to lose that.”