Art World

Yoshitomo Nara Drunkenly Doodled on the Walls of This New York Dive Bar. Ten Years Later, the Mural May Now Be Worth Millions

Nara recently became one of the most expensive artists alive. Denizens of Niagara don't see to care.

Nara recently became one of the most expensive artists alive. Denizens of Niagara don't see to care.

Nate Freeman

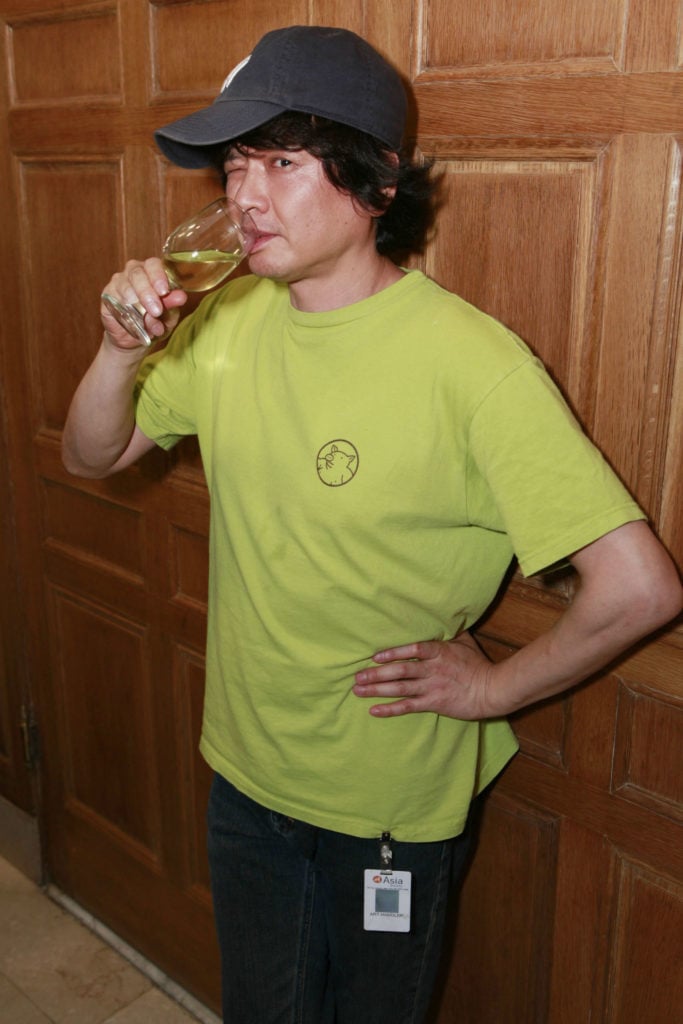

A decade ago, the artist Yoshitomo Nara finished installing a gallery show and got a few drinks at the East Village bar Niagara, a punk scene mainstay on Avenue A that stands out even in a neighborhood full of similar dives. After a while, flush with inspiration, Nara began to draw directly on the walls, conjuring up a bevy of his signature figures: angsty boys and girls, lonely and besotted with rock ‘n roll, banging out tunes on drums and guitars. When he was done, he signed and dated the work, and left.

And then, while waiting for the subway home, he scribbled some graffiti and promptly got arrested by some cops standing nearby. He was taken to the nearest precinct, spent the night in the clink, and made it out just in time to make it to his opening at Marianne Boesky Gallery.

“It’s an incredible story,” said Tim Blum, who has represented Nara since the 1990s. “Nara’s not normally the guy who’s out getting arrested, so that’s a classic New York story of a certain time.” Both he and his partner, Jeff Poe, were in town for that opening in 2009, though now Blum can’t remember if he bailed Nara out or just gave someone the cash.

The bar, on the corner of Avenue A and E. 7th Street. Photo: Nate Freeman.

While the police scrubbed the artist’s scribblings from the walls of the subway, back at the bar the owners did the opposite and installed a plastic screen to protect the works that they had been gifted. A smart choice. This Sunday, Nara’s Knife Behind Back (2000), a large painting of the same frowning little girl present on the walls, sold for nearly $25 million in at Sotheby’s in Hong Kong. Among living artists, only Jeff Koons, David Hockney, Gerhard Richter, and Jasper Johns, have sold works for more higher figures.

The Nara market has entered an echelon where prices for even his drawings and prints are about to go into hyperdrive—and that little dive bar called Niagara very well may have millions of dollars of Nara on its walls, advisers told me. Blum says the work is certainly a Nara, and the artist signed and dated the wall next to the work. An art adviser who is very involved in Nara’s secondary market said that the works, when taken together, could be worth as much as $5 million.

Another said the prices might not be quite so high. Still, the prospect was tantalizing enough that he quipped, “Maybe we should just buy the bar.”

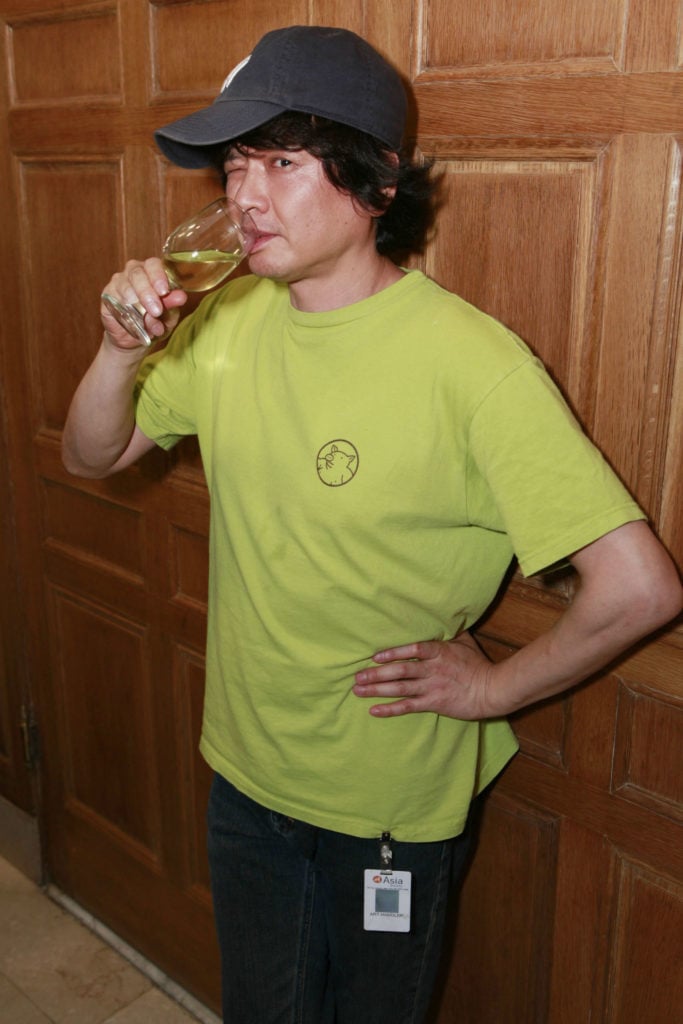

A detail of the mural. Photo: Nate Freeman.

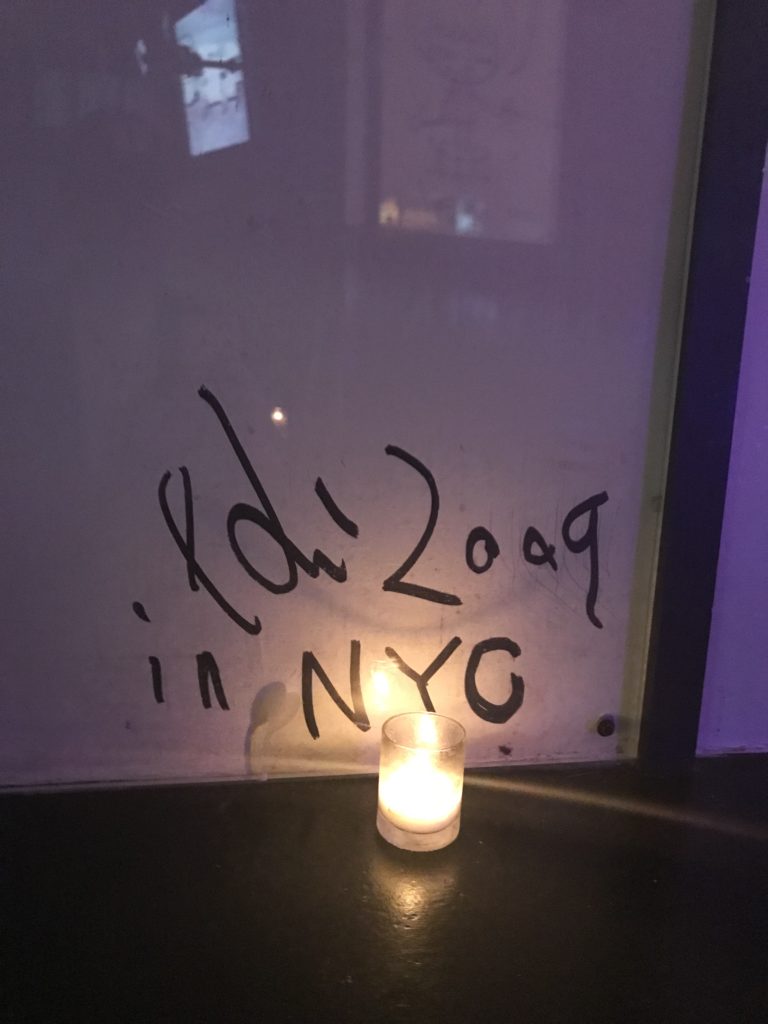

Reviewing how the non-painting Naras have fared in recent years, a multi-million total figure does in fact seem possible. In 2018, a 9-inch-by-9-inch Nara marker-on-paper work, which also depicts his famous cartoon figures, sold for $72,386 over a $27,600 estimate—and that’s for a work smaller than a standard piece of printer paper. At Niagara, the mural is three feet high and eight feet long, with at least five instantly recognizable Nara figures running across its length. There are also three standalone works against the back of the bar, near the bathrooms, and they each feature a large figure as well.

On the mural there’s a punk girl drumming and shouting the Joey Ramone iconic “Hey ho, let’s go!” chant, next to a bass player with a hat that says “staying cool” and a girl with a short haircut banging on a snare. Then, in the three works along the bathrooms, there’s a lead singer yelling “Hey NYC are you happy?” into a microphone, one signature Nara kid pointing to the ladies room, and another kid pointing to the boys.

The work is pure, iconic Nara. Not only does it contain all of his most famous motifs—the little rebel girls, punk rock, text bubbles—but the fact that it’s on a public structure connects him to his heroes Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, who used to make works on buildings in the same neighborhood.

Yoshitomo Nara Knife Behind Back (2000), which sold for $24.9 million this weekend in Hong Kong. Photo courtesy Sotheby’s.

Any price would also reflect Nara’s newly cemented market position after the $24.9 million auction result, as well as the fact that he is about to be the subject of a large-scale retrospective at LACMA (rumored to be moving to the Yuz Museum). When asked about the work at Niagara, Blum declined to speculate what the prices on the secondary market would be, and noted that the work wasn’t technically in any Nara catalogues that have come out. Despite those lacks, the longtime dealer insisted that it was a legitimate work of art, if one executed in a very unusual way, and should be treated as such.

Two Nara works by the bathrooms. Photo: Nate Freeman.

“For me personally, it’s a work of art by Nara. If it’s made by Nara, it’s a Nara,” Blum said. “Objectively, we all know the story. It happened, it’s real, it’s legitimate.”

When asked if—hypothetically—whether it could be sold, Blum said, “I don’t see that there would be anything to get in the way of that.”

Blum noted that it could be offered a la a Banksy (“not that I’m comparing Nara to Banksy”), wherein the owners of a building remove the now-valuable bricks and offer them to the highest bidder. In January, a steelworker in South Wales sold one such small Banksy for a “six figure sum.” A different sort of precedent comes from within the bar and restaurant world: In 2009, the owner of Berlin’s fabulous art boite Paris Bar sold a Martin Kippenberger painting that the artist had made as a tribute to the space and that had hung on its walls for $3 million at Christie’s, to settle a debt.

A work in the back of the bar. Photo: Nate Freeman.

Blum did make it clear that the artist wouldn’t exactly be thrilled to see the beloved dive bar sell the work, though.

“He is loath to get involved in authenticating things for the sake of monetization,” Blum said. “It was an ephemeral gesture that was something in the spirit of a good time, and so when people try to authenticate with a goal to monetize, he blanches. He certainly was there and he certainly created it, but he’s hesitant to embrace it if it’s for money.”

(Calls to the owner of Niagara’s parent company, Tozzer Ltd., went unanswered, and no one responded to an email sent to the address listed on the bar’s website.)

Personally, I’d be devastated to see the bar sell the work to the highest bidder. I live around the corner, and pass by often to hang with Nara’s cute-angry punk kids. When I stopped for a beer one recent Sunday evening, a few hours after the record had been set in Hong Kong, the popcorn machine bubbled with snapping kernels and Paul McCartney and the Clash were blaring. Niagara meets what I consider to be the test of a good bar: roughly half the seats taken, at any given time.

None of the customers were paying particular notice to the artworks on the back wall that night. When I told the bartender that the artist who made them had sold a work for $25 million this weekend, she said, “Is that so!” and went back to pouring a drink. When she returned, she added that she loves the work, and that regulars have embraced the drawings as part of Niagara lore, but that no one ever really thinks about them in terms of value.

Nara himself shares that kind of nonchalance, Blum said. Even though his prices have skyrocketed in recent years, he’s stayed down to earth and remains the same person he was when Blum and his partner first met him, when his works were selling for just a few hundred dollars.

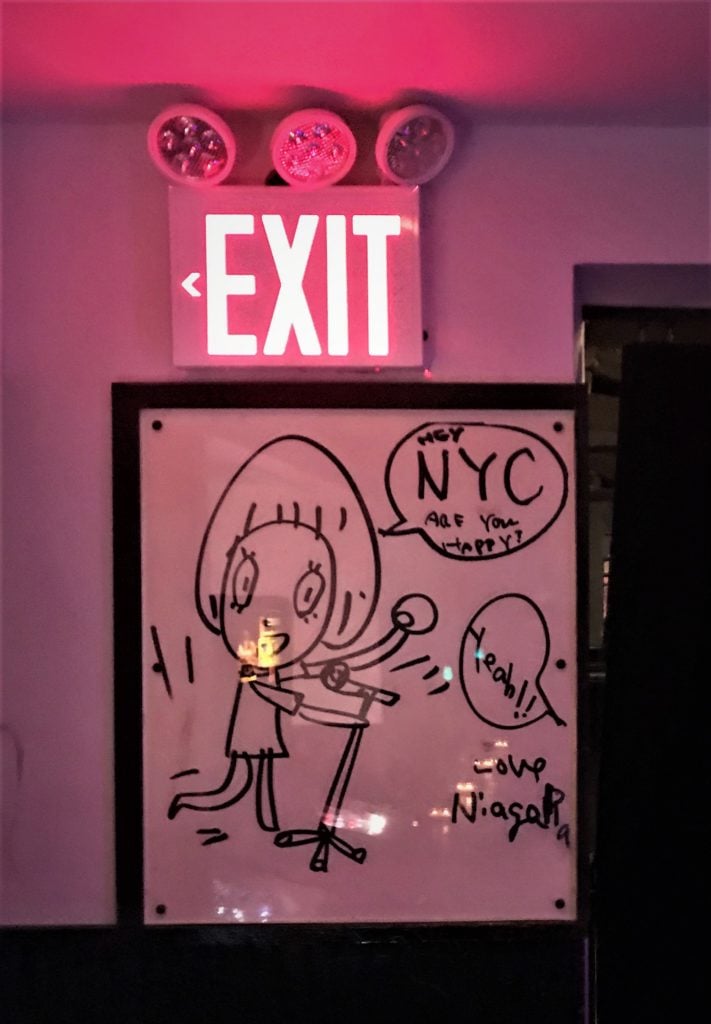

Nara’s signature. Photo: Nate Freeman.

Blum & Poe first sold the now-record-breaking eight-figure Knife Behind Back out of the gallery’s old Santa Monica space, way back in 2001. “I remember the picture so well… I remember the painting hanging on the wall, man, in the white room,” Blum said. “It wasn’t really a no-brainer, easy thing to sell, though we did sell it. It was 20 grand.”

(Given the recent $24.5 million record, that means that the price of the work has increased more than 85,000 percent since it first sold on the primary market.)

Despite being one of the five most expensive artists alive, Nara still has the same taste in dive bars. When he had a solo show with his New York gallery, Pace, in 2017, he insisted on having the “dinner” at Niagara. I was there. It went late.

“Nara’s a fucking great artist and he’s a great guy and he’s grounded and he never sold out,” Blum said. “He follows his own damn rhythm and doesn’t give a fuck. He doesn’t let this shit rattle him.”