Artists

‘Scale Is About Visibility’: Zanele Muholi on Queering Bronze Sculpture

The visual activist reflects on the impact of their practice as they open shows at Southern Guild and Tate Modern.

The visual activist reflects on the impact of their practice as they open shows at Southern Guild and Tate Modern.

Holly Black

Artist Zanele Muholi favors the term “visual activist.” It is an apt term, given they have made it their life’s work to build an archive of imagery that undoes the historical erasure of Black LGBTQIA communities, giving voice and agency to individuals who have often been silenced or had their very existence denied.

“Speaking as a person who deals with issues of queerness, of transness, of ‘the other’ politic, I have not seen many images or sculptures done by our community, which deal with subject matter that makes sense to us,” they explained over the phone. For example, in the series Faces and Phases (2006-ongoing) Muholi creates a record of Black lesbian and trans individuals through self-assured portraits in which participants actively locks eyes with the viewer. In Being (2006-ongoing) the artist captures moments of intimacy between couples and unpicks the notion of queerness being ‘un-African’.

When we spoke, Muholi was on the verge of opening their new show at Southern Guild. The gallery has a founding location in Cape Town and has recently opened a new space in L.A.’s Melrose Hill, where their self-titled show runs until August 31. On the other side of the Atlantic, London’s Tate Modern has remounted a major survey of their work that was cut short by the pandemic (running June 6 to January 26, 2025) and has just reached the end of a subsequent European tour.

On view across these venues are Muholi’s intimate and undeniably beautiful photographs, which are political by their very nature because they demand respect and acknowledgment within institutional frameworks that were not designed to support them.

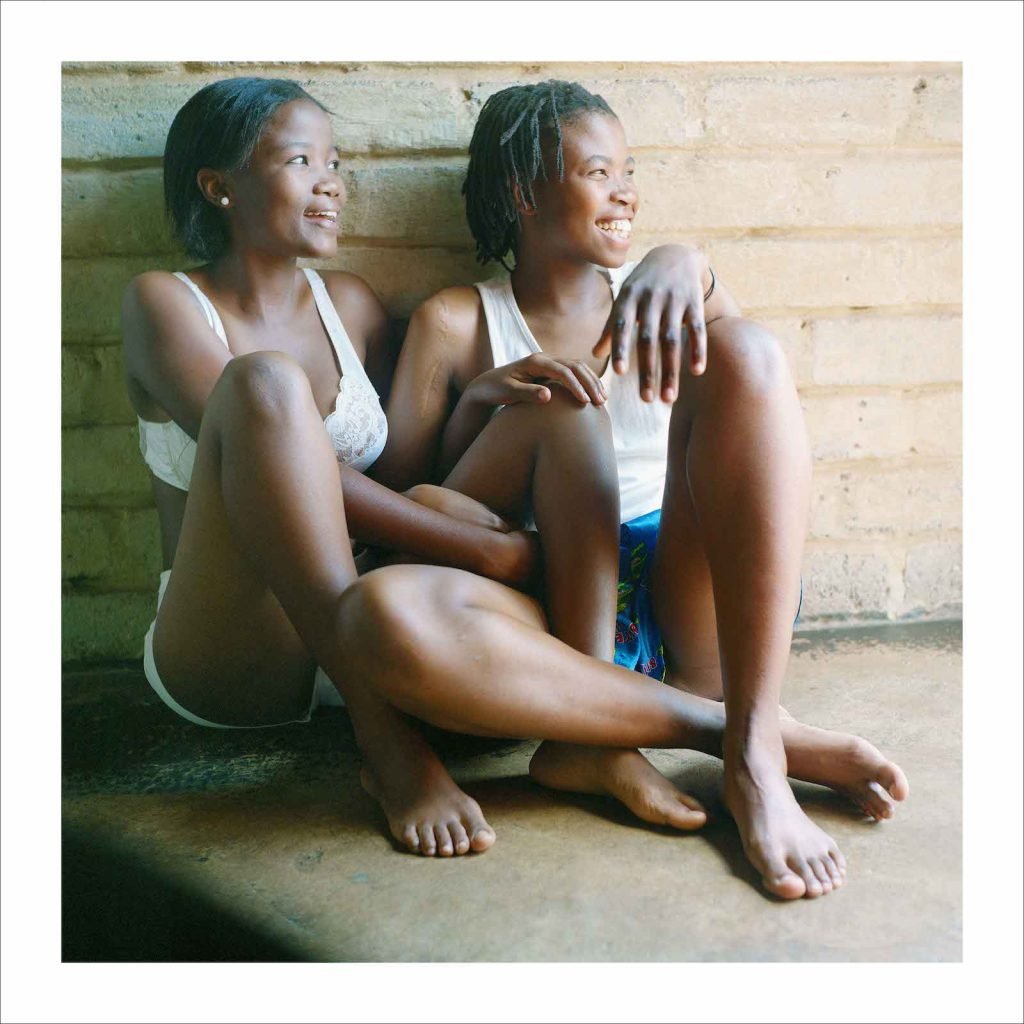

Zanele Muholi, Katlego Mashiloane and Nosipho Lavuta, Ext. 2, Lakeside, Johannesburg (2007). Courtesy of the Artist and Yancey Richardson, New York. © Zanele Muholi.

Art and Well-Being

Both exhibitions present works from across Muholi’s oeuvre, including perhaps their best-known series, Somnyama Ngonyama or ‘Hail the Dark Lioness’, which began in 2012. This ongoing sequence of self-portraiture is produced in highly stylized black-and-white and shows the artist in an array of guises conceived from seemingly everyday objects such as combs, feathers, and pegs.

Muholi’s reference to sculpture is significant, as both shows include monumental new bronzes that many viewers might not be familiar with. These include Umphathi (The One Who Carries) (2023), an enormous uterus with an outer surface of polished gold. A pair of hands gently cup both ovaries, and the interior of the bodily tissue is cast in a contrasting black patina. Another sculpture, Ncinda (2023), depicts the massively upscaled, full anatomy of the clitoris.

Zanele Muholi, Umphathi (The One Who Carries) (2023). Courtesy of Hayden Phipps/Southern Guild.

“There was a lot of confusion attached to that piece, which suggests that people do not know themselves very well,” they said, referring to a previous show at Southern Guild in Cape Town, where it was shown. “It raises questions. How do we educate our communities and learn to relate to an organ that is usually only raised in the context of violence or trauma? Can we familiarize ourselves with these symbols without having any pain attached to them?”

These questions and resulting works were informed partly by Muholi’s own diagnosis of uterine fibroids, and what this meant in the context of gender identity, religion, and access to sexual health and education. At a time when both rhetoric and legislation concerning bodily autonomy are increasingly fraught within the U.K. and the U.S. (not to mention the wider world stage), presenting these works in dialogue with their photography seems particularly timely.

“Artists are human beings with organs; they breathe, they feel, they need, and they care. We are not just boxes of blocks, and we need to be in a healthy state and care for ourselves, to be able to produce or create,” they explained, before adding, “I just wanted to make sure we bring the topic of art and health, medicine, and care, into the space, because these subjects are not often discussed openly.”

Zanele Muholi, Ncinda, 2023. Courtesy of Hayden Phipps/Southern Guild.

Presence and Scale

The enormity of these sculptures, as well as the choice of material, also speaks to the ongoing concerns that Muholi has grappled with in their photography. “The scale is about visibility. It is about being seen, and it is about presence,” they said.

Bronze has been used to venerate and celebrate those in positions of power, and Muholi has sought to harness and complicate that context. “We know the historical effects of bronze throughout art history, but it has never been done in the queerest way. I want to make sure that I am expanding the visual narrative by using a different material. Struggle, resistance, and hardship are attached to its hardness.”

Such visual expansion is something that the artist often returns to. While language might dictate that one “takes” a picture, Muholi’s practice is all about giving and nurturing, as opposed to extraction. Throughout our conversation, they often use the term ‘we’ as opposed to ‘I’, thus situating themselves within a wider community of artists, photographers, activists, and community leaders. There is a sense that Muholi considers their work to be very much a part of a collective movement towards positive change, as opposed to a singular journey.

The artist also references the significance of support offered at the outset of their career, specifically David Goldblatt, the venerated South African photographer who founded the Market Photography Workshop in Johannesburg. “It’s very important to extend the love. When he gave me that opportunity, it meant that I had to do the same for others,” they said. “So far, more than 50 people have benefitted from Muholi scholarships. They don’t owe me anything; they have to extend the love to others and educate others in their own communities, in order for us to capture as much as we can.”

Zanele Muholi, Mellisa Mbambo, Durban South Beach (2017). Courtesy of the Artist and Yancey Richardson, New York. © Zanele Muholi.

This sense of urgency, to build an indisputable archive of human existence, is informed by Muholi’s upbringing. They were born in Umlazi, a township in KwaZulu-Natal close to the coastal city of Durban. When asked when they first picked up a camera, they considered the choice of words. “To say I ‘picked up a camera’ sounds luxurious, because I did not grow up in a space where images are common. Other people can build their family tree by looking at family photo albums, which connect you with your being and your history. I didn’t have those images, so I had to start producing images that made sense to me. I wanted to undo that absence, that lack of imagery.”

Zanele Muholi, Manzi IV, Waterfront, Cape Town, 2022. Courtesy of the artist © Zanele Muholi.

Muholi also expresses the need for photographs that represent the richness of life, not just associations of pain or oppression. “Growing up in Natal in a period of violent transition, the images I saw were not intimate; they could be described as war photography, in the line of duty, where people are fighting over power. They are not the kind of images I wanted to produce.”

Once again citing the importance of agency within their own communities, Muholi states their mission clearly, one befitting of an activist’s sensibility: “We must make sure that we bring a positive image of ourselves into spaces that denied us access before. Visibility is the key word of the day. It means future generations will learn more about our existence. After all, photographs are forever.”