Studio Visit

How Patience and Poetry Inspire Zhou Li’s Radiant Abstractions

Chinese Zhou Li opened her recent solo exhibition at the Shenzhen Museum of Contemporary Art and Urban Planning with a poem. The show, titled “Rose of Light,” takes inspiration from poet Rainer Maria Rilke. Zhou, is an artist who believes in the eloquence of brushstrokes over words. Rather, she sees poetry as a “way out” of the interplay of painting and poetry. Her exhibition poses reflective inquiries by quoting Rilke, such as “If you see one rose, do you see all roses? Or is every flower different?” serves as a gateway to deeper reflection in her work.

Zhou is known for her dynamic abstract paintings that mirror the ephemerality of nature and explore how nature connects with our inner thoughts. Her work weaves together these themes, with brushstrokes that mix poetic lines and soft halos, creating a complex view of reality. She describes her art as “an intermingling of joy and pain, the quest of one’s introspection, and the discovery of nature and oneself.”

Zhou Li in front of her work at her solo exhibition “Rose of Light” at Shenzhen Museum of Contemporary Art and Urban Planning. Photographer: Zaohui@AGENT PAY

Born in the late 1960s to an artistic family, Zhou Li grew up around calligraphy and traditional ink paintings. She moved to France to study in 1994 and started making abstract paintings in 1998. Returning to China in 2003, she settled in Shenzhen, the outpost of China’s reform and opening up, a city synonymous with rapid modernization. It’s not the typical place for mainstream artists, however, this bustling metropolis has become the backdrop for Zhou’s paintings.

Over the last two decades, Zhou has adapted to what is often referred to as the “Shenzhen efficiency” well and has established herself as a leading abstract artist in China. While she makes large-scale paintings in her studio, she also teaches at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, guiding her students on sketching trips around China. Meanwhile, she has been balancing the roles of being a mother of two.

I am intrigued by how she creates such calm amid the city’s dynamism so I visited her studio to chat about how she finds a tranquil “spiritual paradise” against the backdrop of bustling urban life.

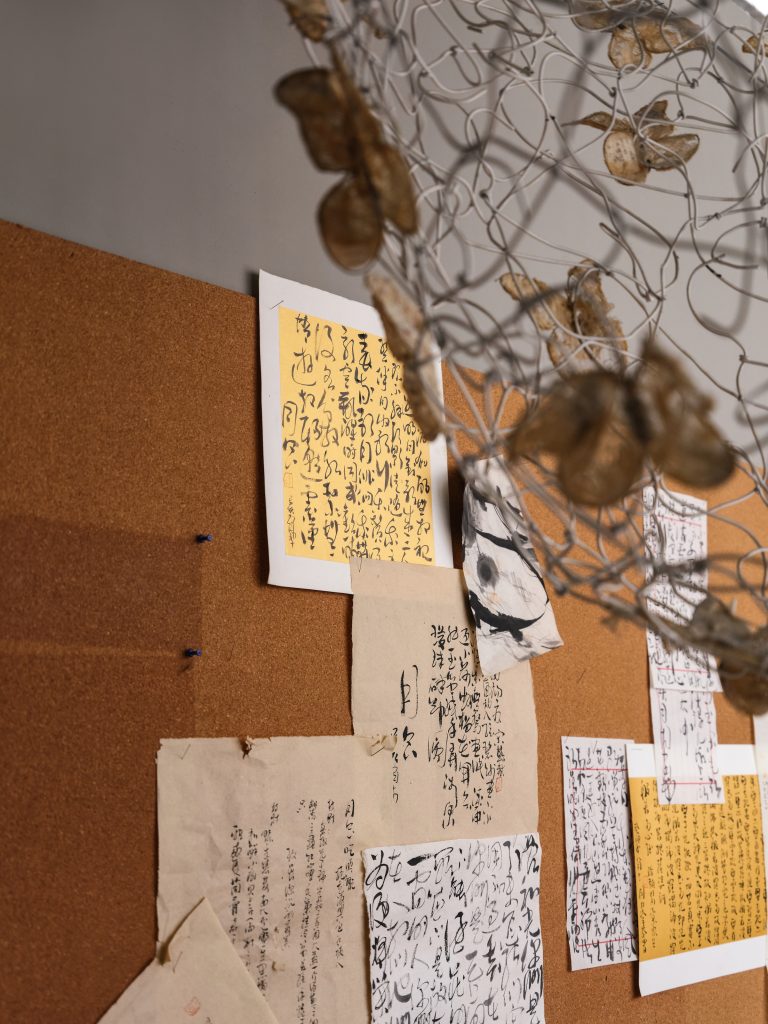

Calligraphy work by Zhou Li in her studio. Photographer: Zaohui@AGENT PAY

There are quite many pieces of calligraphy in your studio, are they all written by you? Can you talk about the relationship between calligraphy and your painting?

I’d hardly call myself a calligrapher but it has been my hobby since I was a child. I practice every morning to quiet myself into a creative state. Traditional Chinese painting and calligraphy share a common origin. Seeing a good piece of calligraphy brings me not only the visual beauty of the form but also provides me with an endless space for imagination. This space can contain everything: in ancient times, it came from the relationship between the self and the world that the artist found in the context of a particular era; today, for an individual, it is still necessary to rediscover this relationship as the context of the times has changed. All of this can be realized in the lines, but it also needs the coordination of the overall picture. For example, the lines can also be colorful, not just black. This kind of color can essentially give the same line a completely different temperament, a kind of abstraction that touches the fundamentals of perception.

Zhou Li in her studio. Photographer: Zaohui@AGENT PAY

Tell us about your studio. Where is it, how did you find it, what kind of space is it, etc.?

Currently, the studio is in Shenzhen OCT Creative Park, the earliest art district in Shenzhen, where old factories have been converted into buildings or design companies, and now there are more small galleries. I’ve been using this studio for about a decade now. It’s a place I’m very familiar with and used to. I’ve spent a lot of time here and it’s become a part of my life. My only regret is that the roof of the building makes it inconvenient to move larger works or sculptures, but it also forces me to think about the transportation of artwork, such as the assembly of the frames and the dismantling of the sculptures.

How many hours do you typically spend in the studio, what time of day do you feel most productive, and what activities fill the majority of that time?

My working phases vary. Sometimes I stay in the studio for a whole day, from morning to midnight, but that does not necessarily mean that I paint much. Sometimes I sit in the studio for a long time. I do calligraphy every day to get myself into the zone. Sometimes although I don’t do anything the process is still necessary. It’s hard to quantify, and it’s definitely not the same as working in an office.

Are the installations hung in your studio also made by you?

Yes. “Plane to solid to plane” is a transformation process, with the same spatial relationships manifesting in different dimensions. The installation sculpture of lines can also be understood as stationary or “in motion” calligraphy.

When you feel stuck while preparing for a show, what do you do to get unstuck?

I don’t think I have ever stuck, as my work comes to me, always naturally.

Installations hang in Zhou Li’s studio. Photographer: Zaohui@AGENT PAY

What tool or art supply do you enjoy working with the most, and why?

Canvas and paint are the most frequently used tools. I also use some huge brushes and they bring me a special feeling. However, I don’t think I can single out a favorite thing. They’re all important, and parts of my work. The large canvases are often placed on a temporary easel, which I like as I’m used to that angle. And the lighting, which has been accurately adjusted, has also been very essential to me.

Is there anything in your studio that a visitor might find surprising?

Regular visitors often wonder what my new works look like. Recently, people have noticed more of a new cat. She was a stray cat before I found her. Some of my friends also notice that the plants in the studio are often changed, some of them have been kept for a long time, and some of them are in vases. My friends are often surprised that I have so many teapots and teacups!

Zhou Li is visited by a stay cat at her studio in Shenzhen. Photographer: Zaohui@AGENT PAY

What is the fanciest item in your studio? The most humble?

There is no difference between fancy and humble; things are all equal to me, just as a flower and a blade of grass are equal.

How does your studio environment influence the way you work?

I think it’s the other way around: my way of working affects the environment and layout of the studio and my working habits. When you enter my studio, if you look closely, you can discover clues of my creative habits. When I enter the studio, I make tea and write, then I start to paint, and in between, I listen to music and read books. This environment can calm my mind, and it is very important for me not to be impatient in the process of creating

What’s the last museum exhibition or gallery show you saw that affected you and why?

It is complicated to measure the impact of what I see in a given moment. Only by searching my memories do I realize that something far away has had a deep impact and has been remembered. One show that affected me was in 2018 at Tate Modern—the Agnes Martin exhibition where reason met sensibility and stillness and approached divinity.

Describe the space in three adjectives.

Natural, living, imperfect.

Zhou Li’s studio in Shenzhen. Photographer: Zaohui@AGENT PAY