On View

‘They Are Used for Great Harm, as Well as for Protection’: Artist Zoë Buckman on the Symbolism of Boxing Gloves and Her Latest New York Show

The artist's latest exhibition considers domesticity, women's work, and the death of her mother.

The artist's latest exhibition considers domesticity, women's work, and the death of her mother.

Sarah Cascone

As she welcomes artnet News into her Brooklyn loft, 34-year-old artist Zoë Buckman is apologetic. Most of her new work is at her gallery, Fort Gansevoort in Manhattan, and her home and studio—a space suffused with gorgeous natural light—is instead something of a mini-retrospective of the artist’s career, full of works she’s shown at previous exhibitions as well a few pieces that didn’t make it into the current show, her first in New York in five years.

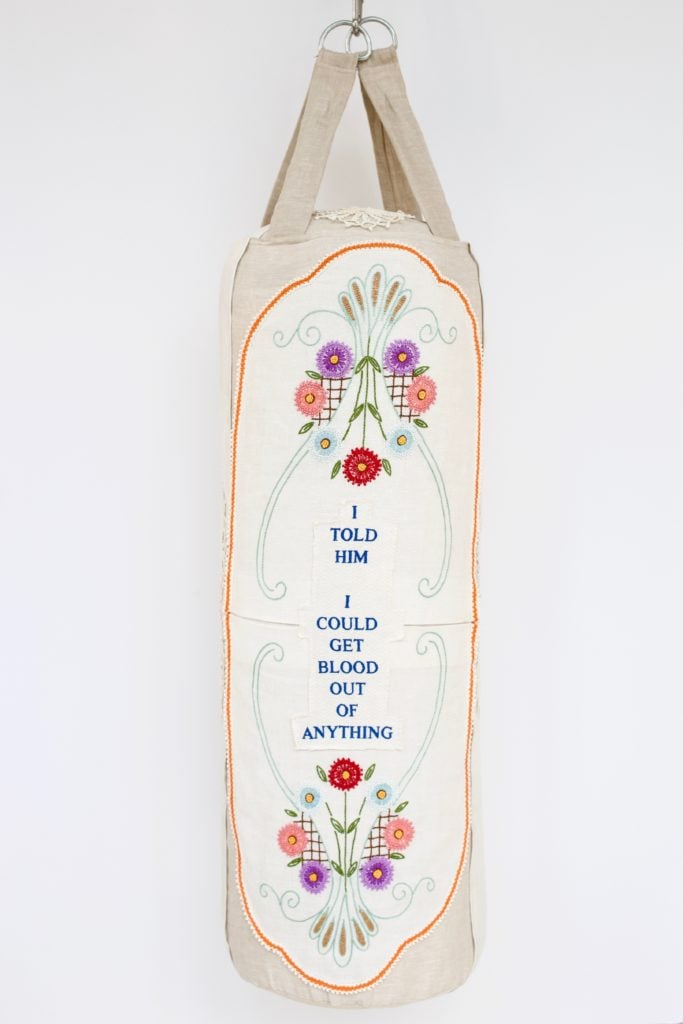

Titled “Heavy Rag,” the personal show expands on Buckman’s series, “Let Her Rave,” which took its name from the John Keats poem “Ode on Melancholy.” A longtime boxer, Buckman began creating sculptures from boxing gloves, covering the supple leather with scraps from discarded wedding dresses, the sparkly, lacy, ultra feminine material creating a dramatic contrast to the familiar shape.

“The form and the symbolism of boxing gloves, with their hard and soft qualities, can be explored artistically and visually in so many different ways,” Buckman said. “They are made with the softest, most beautiful leather, but they are used for great harm, as well as for protection.”

In the new works, she’s swapped ivory taffeta, silk, and chiffon for more domestic fabrics, encasing the boxing gloves in vintage tablecloths, napkins, and tea towels.

Zoë Buckman, His Eyes Harrowed (2019). Photo courtesy of Fort Gansevoort.

The artist, who grew up in London, has been thinking a lot about home recently. Her mother died from cancer this January, and the exhibition is deeply steeped in her grief.

“When my mother got sick, I felt drawn to make work that was more about home and domesticity,” Buckman explained. Jennie Buckman, a playwright and acting coach, was already sick for nine years when she received a terminal diagnosis in early 2018. Her daughter spent much of last year traveling back and forth from London to be with her in her final months.

Buckman’s work has always been autobiographical. Her first exhibition, “Present Life,” in 2015 at Garis & Hahn, then in New York, was a celebration of her experience in becoming a mother. It featured a sculpture created from her plastinated placenta, still prominently displayed next to the desk where she works.

When she began working on her next show in the lead up to the 2016 election, Buckman explained, “I felt like there was this real war on women—which of course there still is—and I was also at the time separating out of my marriage” to actor David Schwimmer, whom she wed in 2010.

“I was in a fight at home and in a fight politically, and I was also beginning to hold my own more in the art world, in this male-dominated space,” Buckman added.

But her work from that period was also emotionally taxing.

“I was working with my wedding dress and other women’s wedding dresses for a long time. My studio was home to a lot of broken dreams and failed marriages,” Buckman said. “I needed to bring color and warmth into my life into my work. Although ‘Heavy Rag’ isn’t about the most celebratory themes, it has felt good to be using fabrics that remind me of my mother and my grandmother.”

Zoë Buckman, Heavy Bleach (2019). Photo courtesy of Fort Gansevoort.

The works in “Heavy Rag” started with a set of tea towels Buckman took back from her mother’s house, and quickly grew from there. She was inspired by the fabric works of Louise Bourgeois, but also by a childhood spent growing up around the kitchen. “We didn’t have a fancy dining area. It was just everyone around this big wooden kitchen table.”

In the past year, embroidery has also been a major focus, giving her “a way to adjust to not having as much time in the studio,” Buckman said. “You can take it on a flight, and I could do it while my mom was resting.”

It’s also the medium that the artist, a graduate of New York’s International Center of Photography, is most comfortable working in. Buckman learned to embroider in school at age 15, in a class that she chose because she thought it would be easy. “And it was,” she says.

Installation view “Zoë Buckman: Heavy Rag” at Fort Gansevoort. Photo courtesy of Fort Gansevoort.

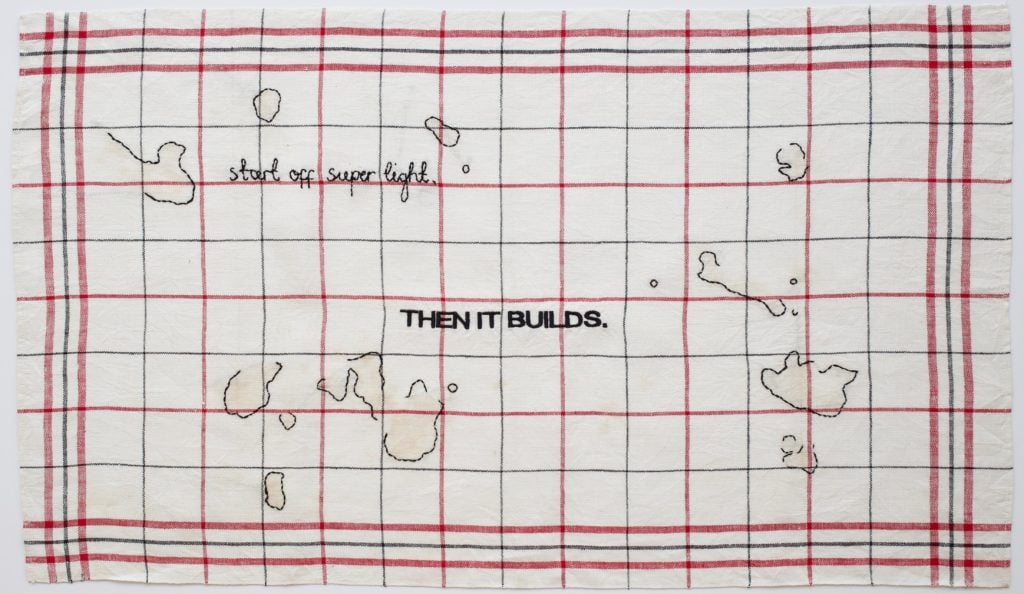

As friends and family learned about her new works, they began offering other household fabrics, things passed down from their mothers and grandmothers. “I’m bringing other people’s memories and their lives into the work, and that’s more meaningful to me than if I went to the store and bought a bunch of new fabrics,” Buckman said. “I like the imperfections as well. Like, that could have been a good night, all the red wine spilled on that tablecloth!”

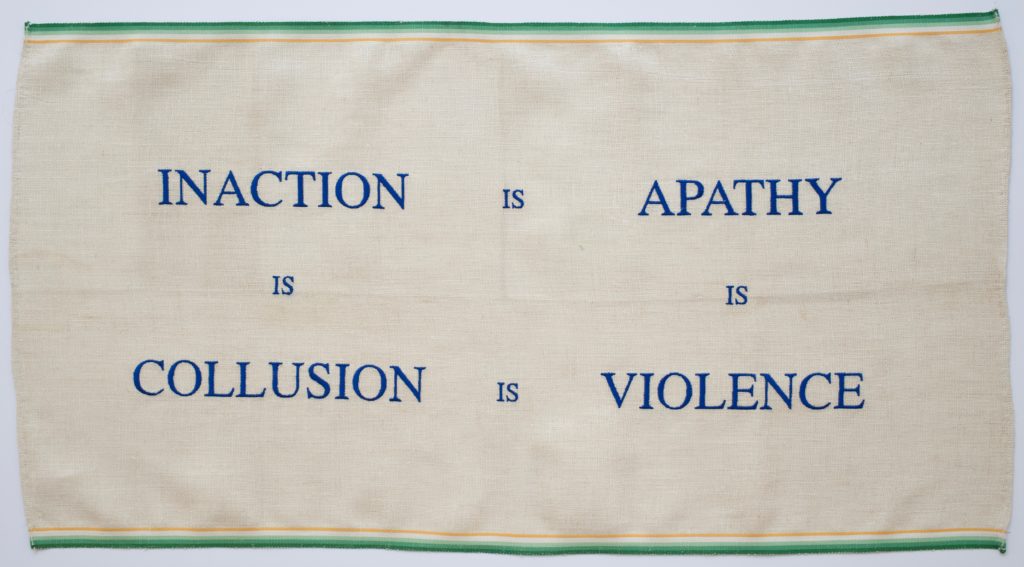

That’s when Buckman began bringing text into the work, embroidering words and phrases that she felt spoke to universal female experiences of heartbreak, loss of power, and trauma. Some of that embroidered text is drawn from her mother’s plays.

“My mom wrote a play for the BBC about first getting her period. She didn’t know what it was, so she applied bleach on her body as well as to her underwear,” said Buckman, who used the lines “It stings, I sobbed” in one of the works. “I didn’t start using her writing until after she passed, and that’s actually my biggest regret. She would have been so proud.”

Zoë Buckman, Sob (2019), from “Zoë Buckman: Heavy Rag” at Fort Gansevoort. Photo courtesy of Fort Gansevoort.

“Heavy Rag” also features an entirely new direction for the artist: Ceramics, which she has been learning to make since March. “Tea really is what keeps my family going,” Buckman explained. “However sick my mom was, she always had to have a cup of tea by her bedside, even if she wasn’t well enough to drink it.”

Buckman she started taking classes at New York’s Greenwich House Pottery, experimenting at the pottery wheel and learning about glazing and firing the porcelain. “There’s definitely similarities to embroidery. It’s very close and detailed, meditative work,” Buckman said, noting that she continued incorporating fabrics, creating imprints in the porcelain with lace doilies and checkered tea towels.

“For the glazes, I wanted to use colors that would speak to bruising and bleeding, and that’s actually quite a lot if you think about it,” Buckman added. “Blue, black, green, red, purple, pink… it was a process of experimenting with a bunch of different glazes and I narrowed it down to about four.”

Zoë Buckman, Like Marmite on Matzos (2019). Photo courtesy of Fort Gansevoort.

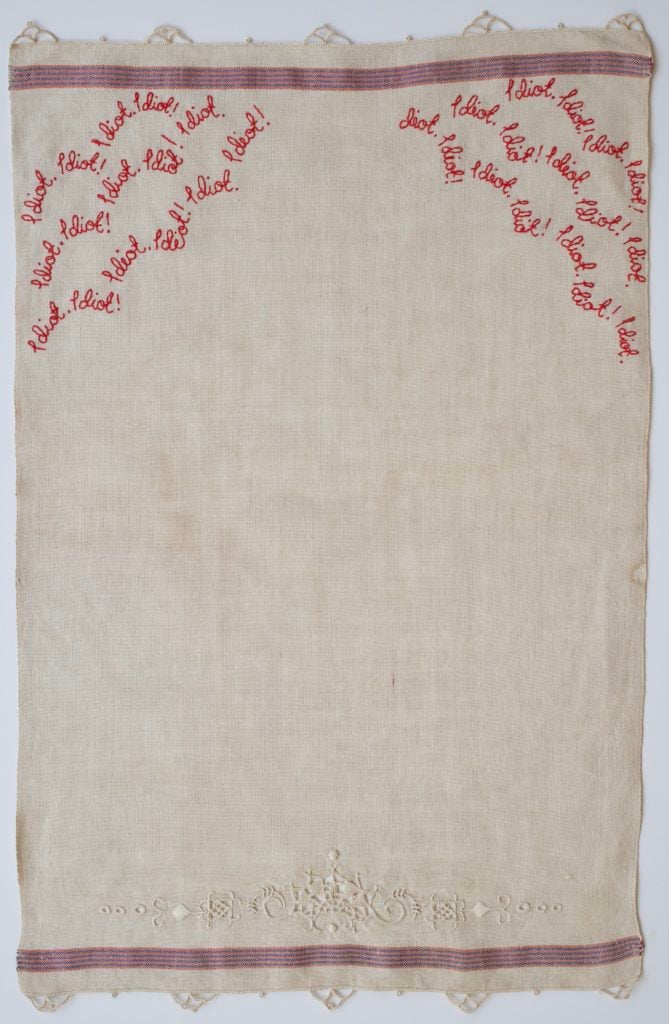

The title of the new show, “Heavy Rag,” of course recalls a crude slang term for menstruation, but it also suggests women’s role in cleaning up, mending scraped knees, and drying tears.

“We’re definitely the fixers,”Buckman said. But there’s also a darker side to that, illustrated by embroidered new works that repeat the word “stupid” and “idiot.” “When something bad happens,” she lamented, “it’s also our fault.”

See more photos from the exhibition below.

Zoë Buckman, Can’t Believe I Was Such an Idiot (2019). Photo courtesy of Fort Gansevoort.

Zoë Buckman, According to Grandma (2019). Photo courtesy of Fort Gansevoort.

Zoë Buckman, The Fucking Master (2019). Photo courtesy of Fort Gansevoort.

Zoë Buckman, Banter (2018). Photo courtesy of Fort Gansevoort.

Zoë Buckman, Inaction II (2018). Photo courtesy of Fort Gansevoort.

Zoë Buckman, Londesborough (2018). Photo courtesy of Fort Gansevoort.

Zoë Buckman, Then It Builds (2018). Photo courtesy of Fort Gansevoort.

Zoë Buckman, Tight Rooted (2019). Photo courtesy of Fort Gansevoort.

Zoë Buckman, Squish Squish (2019). Photo courtesy of Fort Gansevoort.

“Zoë Buckman: Heavy Rag” is on view at Fort Gansevoort, 5 Ninth Avenue, New York, September 6–October 12, 2019.