Studio Visit

In Her Industrial Tel Aviv Studio, Artist Zoya Cherkassky Paints ‘Like Crazy’ While Listening to Talk Radio

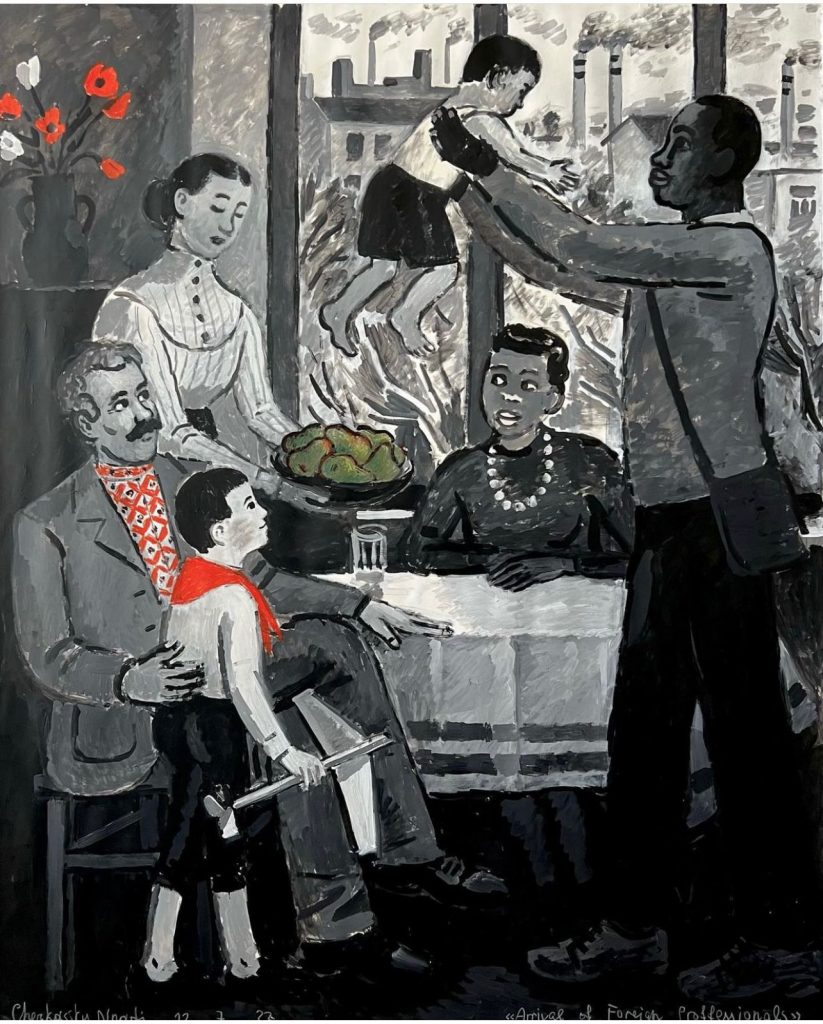

Cherkassky's solo exhibition "The Arrival of Foreign Professionals" is currently on view at Fort Gansevoort, New York.

Cherkassky's solo exhibition "The Arrival of Foreign Professionals" is currently on view at Fort Gansevoort, New York.

Katie White

Ukrainian-born, Tel Aviv-based artist Zoya Cherkassky is what some might call a speed demon—she talks fast, works fast, and thinks fast. In her new exhibition, “The Arrival of the Foreign Professionals,” at New York’s Fort Gansevoort she brings this live-wire energy to a retelling of an often overlooked part of history—the arrival of African diasporic communities in Europe, Israel, and the USSR from the 1930s to the present day.

In creating these recent works, Cherkassky combines historical research with her own memories and her own family story, creating works that cross times and places, with nuance and humor. Cherkassky was born in Kyiv, Ukraine, and immigrated to Israel as a teenager. Cherkassky’s husband is a Nigerian immigrant to Israel as well, with whom the artist has a daughter. These personal and political realities meld together in her colorful, large-scale paintings.

An in-progress image of Centre de Beauté (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Fort Ganesvoort.

In Arrival of Foreign Professionals (after Abram Cherkassky) (2022), the artist reinterprets a Socialist-realist style canvas made by her famous great-granduncle Abram Cherkassky in 1932. The painting was made in an era when Black Americans, in the midst of the Great Depression at home, were being encouraged to immigrate to the USSR, with the promise of a better life. Cherkassky’s painting confronts the complex legacy of her relative’s composition—while hinting at the ongoing reality of such stories.

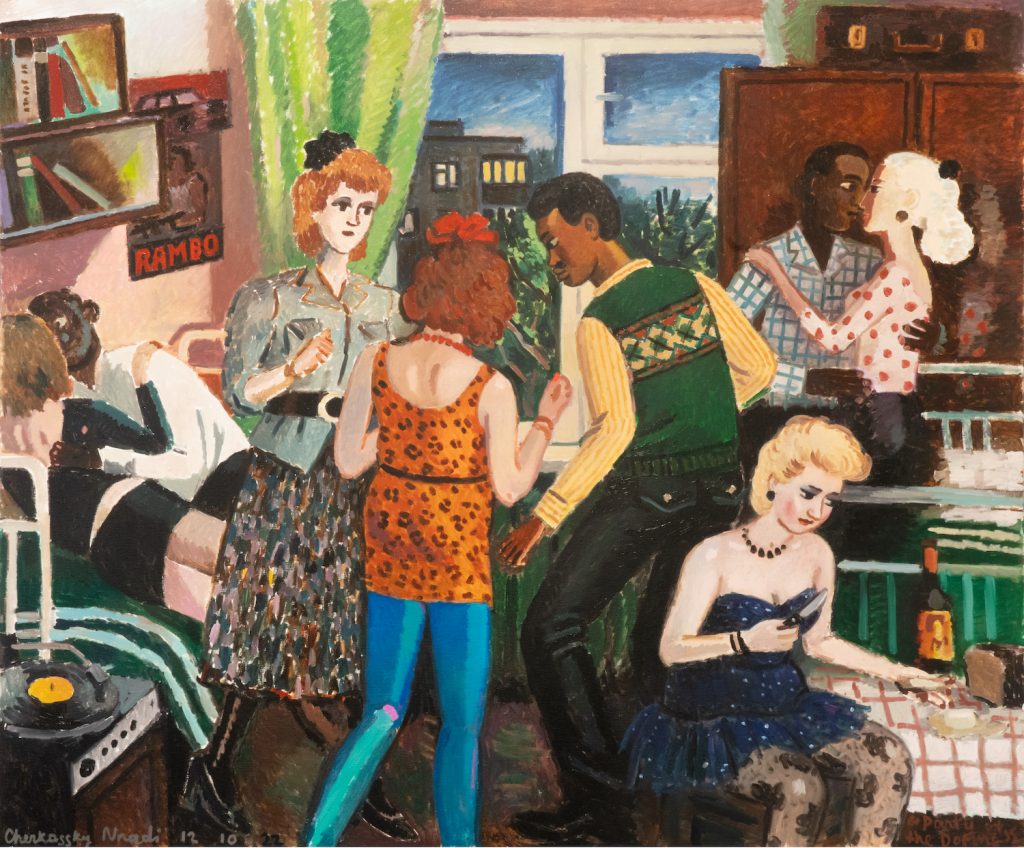

Cherkassky’s images are never didactic, instead depicting everyday scenes—a beauty parlor or a dorm-room party—with humor and vivacity. These recent paintings—most dating to 2022—are among the largest Cherkassky has made and speak to her desire to monumentalize the immigrant experience. She’s also turned to working in acrylic on paper—a medium that allows her the momentum she desires.

Recently, we spoke with Cherkassky about her studio life, from the easel she can’t do without to her studio’s unexpected installation art.

Tell us about your studio. Where is it, how did you find it, what kind of space is it, etc.?

I’ve been in my studio for seven years, but I’ve been in this neighborhood forever. My studio is in an area of Tel Aviv with a lot of artist studios called Kiryat Hamelacha. This is my third studio in this neighborhood—it’s been the last in Tel Aviv that was relatively cheap. But it’s nice because my gallery in Tel Aviv is just next door as well.

Do you have studio assistants or other team members working with you? What do they do?

My assistant’s name is Tanya and we work together all the time. She does many technical things, including stretching canvases and keeping order in the studio. And she helps with the works themselves.

Can you send us a picture of a work in progress in a way that you think will provide insight into your process?

An in-progress image of the painting Arrival of Foreign Professionals (after Abram Cherkassky) (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort.

What materials do you enjoy working with the most, and why?

I use whatever I have on hand. When I do my small sketches, I always use whatever paper I have on my table. My bigger paintings are often acrylic on paper. I was paintings with multiple figures and when you do it in oil, it’s very hard to move because it takes time to dry. I thought I would make a Renaissance fresco-type of preparation, a drawing on paper and then I move the compositions to oil. I did one, and then I did a second, and then I could not hold back to just black and white anymore and just kept working this way, adding color. I really like the speed it allows me.

What kind of atmosphere do you prefer when you work? Is there anything you like to listen to/watch/read/look at etc. while in the studio for inspiration or as ambient culture?

Tanya and I usually listen to something stupid—anything that does not distract my attention. I put on some dumb TV or radio show—the stupidest talk show possible. When somebody’s coming to the studio I say, “Tanya, let’s turn it off since I don’t want them to think we’re idiots.”

Several of the paintings in the show reference photographs from your family, others seem drawn from real-life. How do you begin your work?

I usually start with sketches, at times made from observation or the imagination. But I also use photos as a reference. I never work directly from a photograph but they help me recall the pattern of a dress or the text on a street sign—those kinds of details. It’s a combination of references.

Zoya Cherkassky, Party at the Dorms (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort.

Do you have a favorite work in the exhibition at Fort Gansevoort?

There is a painting, Party at the Dorms, that shows dancing in Soviet dorms. There was a university in Moscow that hosted students from developing countries—these were supposed to be simple guys, but they were often the children of influential people. For us girls, it was the only chance to meet someone from abroad and they seemed cool because they could have dollars—which were forbidden. Sometimes there were parties like this one in the university dorms. My sister married a student from Jordan who she met at one of these parties—so she was my consultant for this painting. I wanted to go, of course, but I was 14 at the time—too young so my mother wouldn’t let me. But, still, there was the allure.

How do you know when an artwork you are working on is clicking? How do you know when an artwork you are working on is a dud?

It’s intuitive. I know a work is clicking when nothing is disturbing me anymore. Sometimes it happens that work dies, you know? Then I just cut it in pieces and throw it out.

Courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort.

Is there anything in your studio that a visitor might find surprising?

For a previous project, I built a Soviet-style apartment in my studio. I needed it for my paintings so I collected stuff and then built it. One of my collectors brought me some items from Moscow to make it seem more legitimate.

What’s the last museum exhibition or gallery show you saw that really affected you and why?

I visited New York to see the Alex Katz show at the Guggenheim—I don’t think there will there be an exhibition of his work this big again in my lifetime. I like Alex Katz because he’s not afraid to make huge paintings.

Do you have a most essential tool in your studio?

I have a very old easel that used to belong to my gallerist in Tel Aviv. It was his father’s and he used it to display paintings on it. I saw it one day and I was like—I need that. It’s a very good easel because it has a handle that goes from the ground up. I love it.

Is there a way you like to structure your day in the studio?

I arrive and then I paint like crazy.

“Zoya Cherkassky: The Arrival of Foreign Professionals” is on view at Fort Gansevoort New York through June 3, 2023.