Gallery Network

7 Questions for Chinese Artist Lu Junzhou on Freeing Contemporary Calligraphy From the ‘Shackles of Text’

Lu uses calligraphy as a starting point for new and expanded modes of artistic creation and self expression.

Lu uses calligraphy as a starting point for new and expanded modes of artistic creation and self expression.

Artnet Gallery Network

Chinese artist Lu Junzhou (b. 1974) has an artistic practice rooted in the traditions of calligraphy and ink painting. Over the course of his career, Lu has developed his own artistic vernacular, drawing from the history of both Eastern and Western artmaking traditions. These influences wed in his Chinese calligraphic works created through a distinctly contemporary lens.

Lu’s work offers insight into the vast possibilities, both realized and potential, that calligraphy offers as a contemporary practice; though frequently working in two- dimensional mediums, the artist has also worked in installation. At the 2021 exhibition at the Liangzhu Culture and Arts Center in Zhejiang province, his work Stones with a thousand characters was comprised of hundreds of stones shown circularly. Ultimately, Lu’s employment of Chinese characters offers viewers—despite language barriers—the opportunity to experience and appreciate the logograms and their capacity for creative expression.

We recently caught up with Lu to learn more about his artistic journey, and what he aims to work with next within the genre.

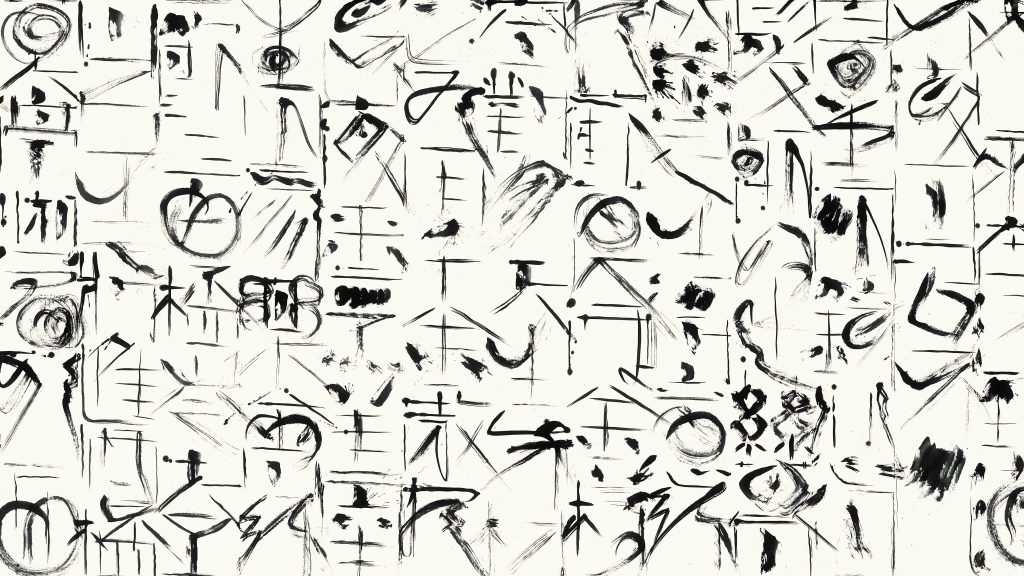

Lu Junzhou, Saddened by Solitude (2020).

Though you began studying calligraphy as a child and were very active in the calligraphy scene as a teenager, it wasn’t until 2010 that you started your own artistic practice. What led to this evolution in your work?

I grew up in the countryside of Yongjia, Zhejiang Province. At that time, handwriting was a skill, which may be because it is a tradition for people in Yongjia to attach the same importance to farming and the education of family members since ancient times. Calligraphy is closely related to life. People will be invited to write couplets for festivals, weddings, and funerals, as well as the inaugurations of new houses. Additionally, people will be invited to write the names of owners on items such as farmers’ household goods and farm tools. Government slogans need to be written. If you can write well in your local area, you will be respected and busy. My father always stressed to me, “handwriting is a person’s other appearance.” After entering junior high school, the deepening of reform and opening of the country brought the prosperity of society as well as the craze for literature and art. The development of media gave me—although I lived in an isolated village at that time—the opportunity to participate in various national exhibitions and competitions. That’s when I began to enter the calligraphy circle. In the 1990s, when I was out of school, I was faced with a series of practical problems. During the following ten years, I lived a life of uncertainty, however, I never put down the brush. In 2003, I settled in Beijing and engaged in art-related jobs. With the rise of Chinese contemporary art, I felt that new things brought new thoughts. During my trip to Europe in 2007, I visited Kassel Documenta, Venice Biennale, Art Basel, etc. I also visited many art galleries and museums. Not knowing much about traditional Western and contemporary art, I had a feeling about art that I had never had before in a trance. In 2010, there were some changes in my life and work. I had some new thoughts on my work and life, especially on calligraphy. I also firmed up my understanding and perception and started a new practice.

Lu Junzhou, Bring In the Wine (2021).

What does your creative process look like? Do you have a clear vision when you start or is it more organic and intuitive?

Some are planned, some are not planned. For example, in the two solo exhibitions I have held, I made some plans that took into consideration the space and scale of the museum, as well as the humanistic elements of the host place and the exhibition theme. But when you get into the creative state, it becomes unplanned again, and, ultimately, it’s your intuition that determines everything. In my daily creation, I feel more in reading Chinese classical poetry. Chinese characters are symbols of wisdom, expressive, and can directly communicate with people. Poems and verses combined by excellent poets and writers will make Chinese characters more charming. I always have a strong impulse to write when reading.

What role does history or tradition play in your artistic practice?

Almost all of my works rely on history and tradition. The artistic conception and cultural atmosphere presented in traditional Chinese calligraphy and painting have impressed me greatly, and I especially hope that my works can have these feelings. Maybe history and tradition are more of a treasure trove for me. I can go to this treasure whenever I want to find what I want and solutions.

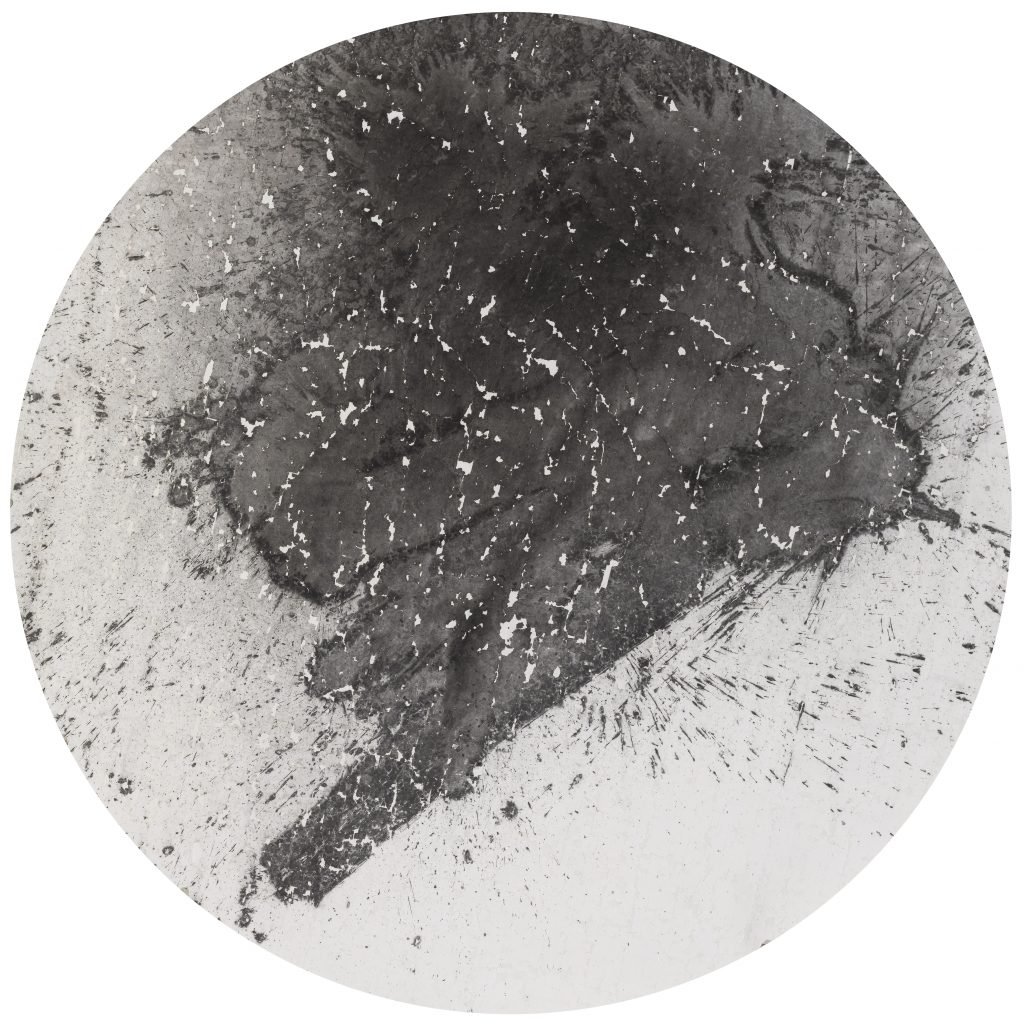

Lu Junzhou, Dream (2018).

I read that you aim for “de-textualization” in your calligraphic work despite frequently centering on text. Can you expand on this idea?

“De-textualization” is not my goal. I just think that calligraphy, as an independent art, should exist independently. Text is only one of its elements, and my creation is very dependent on text. I especially hope that when the viewer faces my works, they can feel my calligraphic language rather than the content of the text. Of course, I also think about whether calligraphy would have more freedom if it could get rid of the shackles of text. Maybe…

Where do you usually look for or find inspiration? Are there any movements, events, or experiences that have influenced your work the most?

For me, inspiration is uncertain and fleeting. It may be the dribs and drabs of life, a poem, a work of art, a shot in a movie or television, or a picture imagined in a daze and wild imagination. Of course, anything that happens at the moment might get my attention.

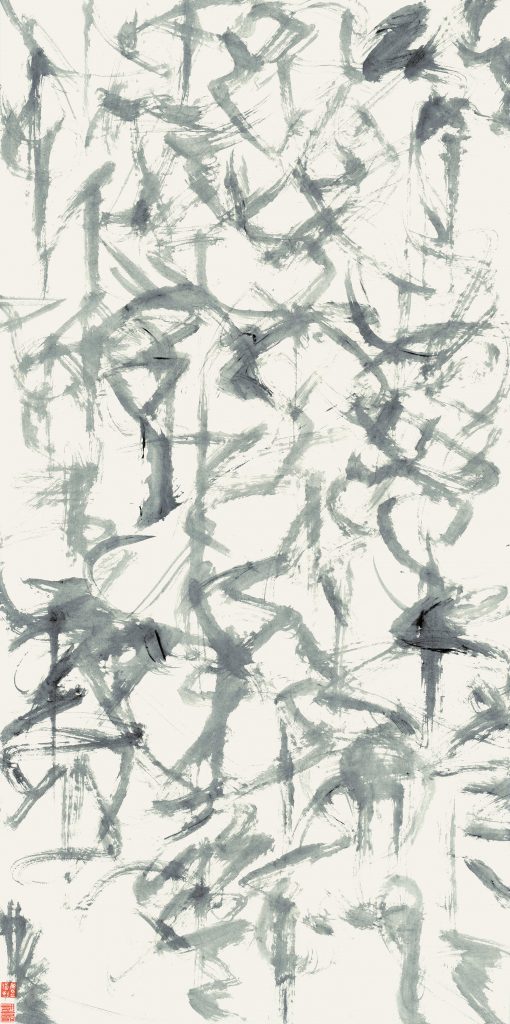

Lu Junzhou, Fragrant Like Before (2020).

What would you like viewers of your work to take away with them, or their experience to be like?

I hope that my works can give viewers a visual experience that they have never had before. I also hope that viewers can put down some formatted presuppositions on calligraphy, a traditional art, and feel and experience everything happening in the moment with an open and pure mind.

Can you tell us about what you are currently working on, or hope to work on next?

After holding the solo exhibition “Writing Liangzhu” in Hangzhou in 2021, I hardly felt like writing. At the beginning of last year, I set up my new studio near Songzhuang in Beijing and moved my home to the studio. I have a lot of imagination for my future creations, and my next job is to present these imaginations one by one. I’m really looking forward to my new works.

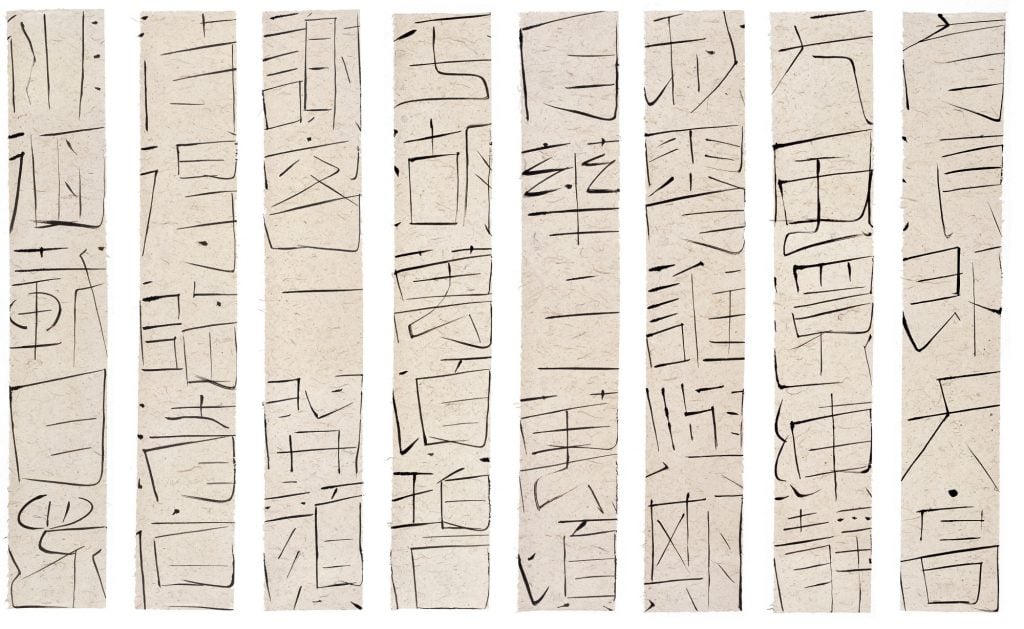

Lu Junzhou, Very First Feeling (2010).