Buyer's Guide

Pioneering Digital Artist Eduardo Kac on his Controversial Career And Sending His Art Into Space

The artist will present his project “The Time of the Chimeras” at Venice Biennale this April.

The artist will present his project “The Time of the Chimeras” at Venice Biennale this April.

Cynthia Tian

During the 1980s, artist Eduardo Kac began experimenting with digital art, aiming to carve out a space for art and poetry in the newly emerging space. Now, some forty years later, the artist is continuing to experiment with new digital, even scientific, mediums. This month is a busy one for Kac. The artist is debuting a new project “The Time of the Chimeras” at the Venice Biennale this April, as well as two exhibitions, “Eduardo Kac: From Minitel to NFT” at Henrique Faria Fine Art in New York City and “Inner Telescope” opening in Chicago.

Recently Cynthia Tian, a digital media communicator and correspondent, interviewed Kac in a Twitter space event organized by Global Crypto Art. In the conversation, Kac shared his thoughts on his early digital creations, his bio-art trilogy, olfactory art, and space art.

You started producing digital art in the early 1980s, amid the Neo-Expressionist art wave. The art world was less interested in technology than colorful and big-scale paintings. What motivated you to take on digital media?

I was 20 years old in 1982. I understood very early on that the digital revolution marked the beginning of an entirely new cultural phase. More importantly, I understood that in the digital future there would be room for art and poetry. I’m interested in the past profoundly. But, the fact that I have a cultural interest in the past, does not mean that I want to live in the past. I wanted to build a future. I wanted to live in this future that I had imagined.

The conceptual artists of the ’60s and ’70s worked with formats in which the materiality of the artwork was not so central. Well, I am not a conceptual artist. I wanted to develop this other world in which new art forms would emerge. So, for me the digital world marked the beginning of an age in which the work was not dematerialized, the work was directly immaterial. This shift allowed the digital to be understood, not just as a medium, but as the motor of an entirely new culture. It is in essence what motivated me to develop artworks and poems for this new era.

Your digital art was groundbreaking. Many consider you a pioneer of the digital art world. What is your assessment of your own impact?

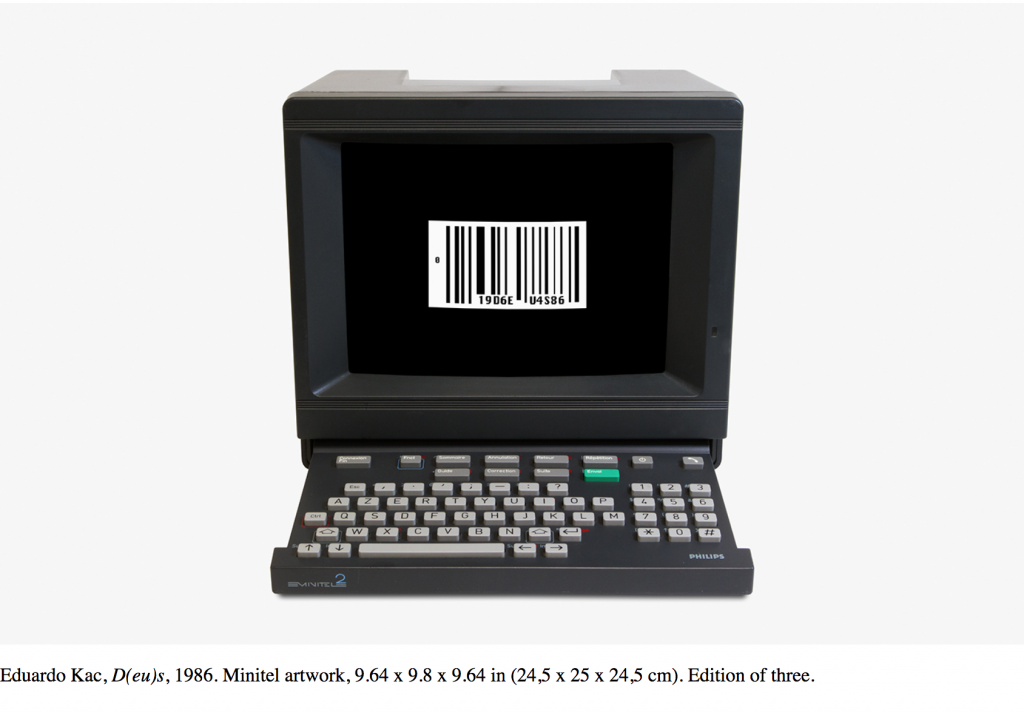

This question would be best answered by others. But I have a solo show in New York at Henrique Faria Fine Art opening on April 28, which is called “Eduardo Kac: from Minitel to NFT”. This exhibition can be viewed as a career survey specifically in regard to my digital art practice.

What is a Minitel? Are there any vintage systems from the ‘80s and ‘90s included in this solo show?

Minitel was an early network that was developed primarily in France. Different countries also had this network: the U.S., Japan, Canada, and a few others. But it was best known and was most successful in France in the early ’80s.

This network existed before the web and does not exist any longer. And that idea alone is interesting: the idea of the birth and death of networks. And what it means to artworks that are made in and for these networks that no longer exist.

In the exhibition, there will be works from the ’80s, works from the ’90s, and works from the 21st century, all of them are digital, many of them running on vintage machines. I spent 15 years restoring my Minitel artworks. Now that that is completed, I am continuing to restore some of the other early work. There will be four Minitel pieces in the show, each running in its own terminal, as well as an Apple III from the early ’80s and an interactive work running on a Mac classic from 1993. These are vintage machines with vintage files running on vintage operating systems. The Apple III was written in Basic programming language.

Many people first heard about you through your work GFP bunny (2000) a project that granted you both fame and a fair share of controversy. The center of the work was the very real rabbit Alba, an albino rabbit engineered by splicing the green fluorescent protein of a jellyfish into her genome. Can you tell us more about the project?

GFP bunny is part of a three-piece series, my Creation Trilogy. GFP means “green fluorescent protein.” On the material level, I used GFP on these three works. I worked with bacteria, which is to say single-celled organisms, the simplest form of life. At the other end of the spectrum, I created a green glowing rabbit which is the one that you are alluding to and her name is Alba, a multicellular organism. This creates a spectrum between the simple and the most complex.

My third piece in the trilogy is The Eight Day, in which I created an environment where there are several green glowing organisms that cohabited and shared the same space. In the center of this environment, there is a robot, a robot that is very specific. There are green glowing amoebae inside this robot that control the legs of the robot. And the eye of the robot is controlled by human participants. The observable behavior of this robot is partially controlled by humans and partially controlled by amoebae.

Given the fact that they all glow green in this work, the notion of difference based on green fluorescence disappears internally. Since they don’t glow green, in this work humans are the ones that are “different”.

In your work Natural History of the Enigma you inserted your own DNA into a flower. Was the plant able to produce human protein, as you expected?

That was the key point: for the flower to use my DNA and produce a human protein in its body. And in fact, that does take place. We have to remember that flowers do not make human proteins in nature, but in this particular case, it does, because my DNA is placed under the control of a promoter that triggers the production of that protein. And because humans are animals, this flower is a plant with an animal characteristic, which in this particular case is the production of a human protein.

The Creation Trilogy seems to explore the boundaries between different living groups. Let’s say, the boundary between humans and animals, humans and plants, and animals and plants, amoeba and robots. You seem to question and test these boundaries. Is this a part of your intention?

You’re absolutely right and that is definitely a tenet of my practice. Because I feel that these boundaries are arbitrary, and they end up serving specific purposes. You see, for the longest time, we have looked at the world through the prism of dichotomies.

The notion of “the human” was articulated in opposition to what was understood as “the animal”. The human was in opposition to machines. This logic of opposition very often served the purpose of establishing hierarchies. One hierarchy indicated that the human was better, more important, superior to others. The same hierarchy replicated itself and started to unfold in other areas where men were seen in opposition to women, for example.

I think that we must demonstrate that, in reality, there isn’t an opposition, there isn’t a hierarchy. We’re all different, but we’re all interconnected. The moment we begin to undo these hierarchies we can see ourselves in a different light where there is more equity.

Take the case of my Natural History of the Enigma, in which I transplant human DNA into a flower. It becomes very clear that even after almost 4 billion years of evolution of life on Earth, we still remain connected to other life forms that we perceive to be fundamentally different.

We often use the power of opposition and judgment in our societies and on ourselves. You once stated that the olfactory sense is generally considered the lowest of all human senses according to our cultural tradition. How did you make this observation? As an artist, how do you undo this hierarchy of senses through your artwork?

It’s a very powerful experience, the experience of smell. And it is commonly known that smells trigger memories. I am deeply involved with and interested in language itself. But the experience of scent bypasses language and communicates in a very powerful, emotional, and direct way.

Perhaps this is the reason that the olfactory sense is associated with animality. We have a very complex auditory culture, think of Mozart and Beethoven. We use a complex language to talk about visual art, music, and wine. But we do not have a complex language for olfaction. That is because, traditionally, we have not considered olfaction as significant as the other modes of sensory perception. Not having the means to communicate, we continue to subjugate and suppress the olfactory sense. This process creates a vicious circle.

I have two series of olfactory artworks “Aromapoetry” and “Osmoboxes.” In these art pieces, I undo this hierarchy by connecting us with the most suppressed of our senses, by elevating it and making it the primary means of aesthetic experience.

As we speak, one of your “Space Art” pieces is in orbit around the earth aboard the International Space Station. Tell me more about this work.

The space artwork that is in orbit is called Adsum. It was created in my studio and then flew to the International Space Station on February 19th, 2022. So, it’s in orbit as we speak. Adsum is Latin for “Here I am”. There was an earlier series called Inner Telescope, which was realized aboard the International Space Station with the cooperation of a French astronaut. In this series, there are videos, photographs, embroideries, drawings, prints, and artists’ books. These bodies of work convey the sensibility of imagining (and producing) art outside of planet Earth.