On View

On the 350th Anniversary of Rembrandt’s Death, the Artist’s Hometown Is Staging the First Show Dedicated to His Early Work

How did the town of Leiden shape young Rembrandt?

How did the town of Leiden shape young Rembrandt?

Katy Diamond Hamer

This year marks the 350th anniversary of the death of artist Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, and the Netherlands is commemorating the historic occasion with a series of exhibitions around the country. One of the more interesting events is taking place in Rembrandt’s hometown of Leiden, a show at the Museum De Lakenhal that goes all the way back to the artist’s roots.

“Young Rembrandt—Rising Star,” which has been 10 years in the making, is the first comprehensive overview of the artist’s earliest work. One particularly important painting, Spectacles Seller (Allegory of Sight), made in 1624, when the artist was just 18 years old, is on view, as is Self-Portrait from 1635, the year Rembrandt officially moved to Amsterdam. The Leiden museum houses Rembrandt’s archives and is the place where many of these paintings originated.

It is believed that the artist had a working studio in Leiden until 1634 and traveled back and forth between the two cities, perhaps in the same way an artist today would travel between New Jersey and Manhattan.

Rembrandt van Rijn, A Peddler Selling Spectacles (ca. 1624). Courtesy of Museum De Lakenhal, Leiden.

“It was a coincidence that he was born in Leiden, but a fortune,” said Rembrandt biographer Onno Blom. “If there is a ‘golden future,’ Rembrandt must have realized that by being a great painter, he could be famous if he left Leiden and went somewhere else. Upon leaving and going to Amsterdam, he achieved this goal.”

While not quite a village, the municipality of Leiden currently has a population of 124,000, compared to Amsterdam’s 867,000. For Rembrandt, the bigger city afforded him the opportunity to receive portrait commissions from wealthy patrons. Even during the Golden Age, pockets of poverty existed in Leiden, along with radical religious discrimination between Catholics, Calvinists, and Protestants. Rembrandt, a Protestant, faced less discrimination in the more liberal Amsterdam.

“Many good, young artists went from Leiden to Amsterdam at the time. There was an exodus of talent, which we’ve seen in other places as well, such as in the 1930s in Germany,” said Christiaan Vogelaar, one of the exhibition’s curators. Hanging in the exhibition is a map of Leiden, pinpointing where Rembrandt lived, worked, and studied. The route has been laid out so that visitors can retrace the artist’s steps, all within a short walking distance of the museum. “The atmosphere and scale of this city are feasible,” Vogelaar said.

Another highlight of the exhibition, on view for the first time, is the canvas Let the Little Children Come to me (circa 1627), which was acquired in a 2014 auction in Cologne. After a rigorous restoration process, top layers of paint were removed, and more of the hand of the artist has been revealed. A figure in the upper right side of the painting has also been identified as one of the many self-portraits Rembrandt made throughout his lifetime. “Rembrandt made a cameo in this painting, like Hitchcock, he makes an appearance and then disappears,” Blom said.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Let the Little Children Come to Me (ca. 1627–28). Courtesy of Jan Six Fine Art, Amsterdam.

This too could be a metaphor for the cultural residue, imprint, and legacy that the artist left in Leiden. A historically rich city in many ways, but still lesser known than Amsterdam, sculptural tributes to the artist can be found on several of the narrow brick streets. “I walked the city day after day, hoping for the ghost of Rembrandt,” Blom said of the process of writing his newly published book, also titled Young Rembrandt. “You can sense him, but can’t really get a complete grasp in the same way it’s difficult to understand how he made his first etchings.”

Just as Michelangelo breathes air into Florence and Andy Warhol haunts the streets of Pittsburgh, “Young Rembrandt” brings the phantasm to life.

“Young Rembrandt, Rising Star” is on view at the Museum De Lakenhal, Leiden, Netherlands, through February 9, 2020; see highlights from the exhibition below.

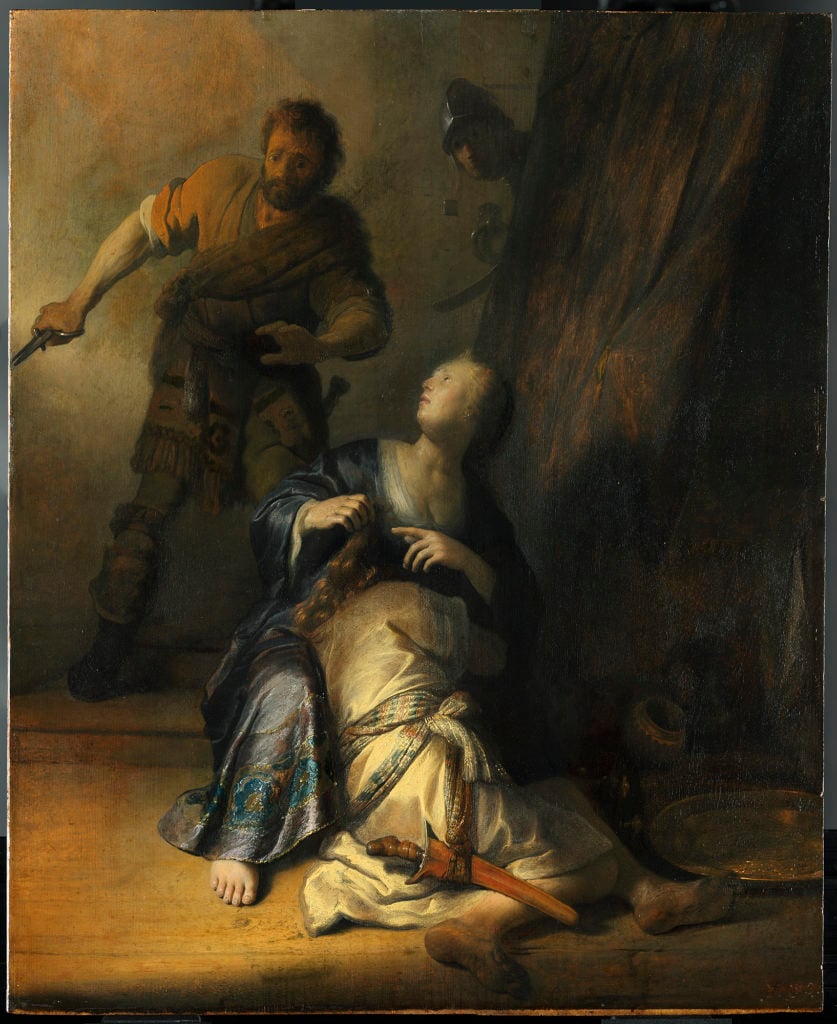

Rembrandt van Rijn, Samson and Delilah (1628). Courtesy of Gemäldegalerie Staatliche Museen Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz.

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Abduction of Europa (1632). Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Man in Oriental Costume (The Noble Savage) (1632). Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Portrait of an Old Man (Rembrandt’s Father) (1625–30). Courtesy of Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford.