Reviews

Designer JW Anderson Brings ‘Disobedient Bodies’ to the Hepworth Wakefield

His show is a meditation on the human form as re-imagined in sculpture, fashion, ceramics, dance, and design.

His show is a meditation on the human form as re-imagined in sculpture, fashion, ceramics, dance, and design.

Hettie Judah

The latest development in the art world’s off-again, on-again romance with fashion comes courtesy a fecund hook-up between the Hepworth Wakefield and designer JW Anderson. On Thursday last, elegant, Yorkshire-based Hepworth (6) and boyish, Derry-born Anderson (32) glowed with pride at the first public outing of their offspring, the handsome exhibition “Disobedient Bodies.”

Some 18 months in gestation, “Disobedient Bodies” is a meditation on the human form as re-imagined in sculpture, fashion, ceramics, dance, and design. It is no discredit to Anderson’s art world chops that the undertaking was developed as a “group conversation” with the Hepworth’s chief curator Andrew Bonacina and Stephanie Macdonald of 6a Architects. The result is a beautifully arranged collection of objects, ranging from sculpture by Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore, Magali Reus and Anthea Hamilton, through anthropomorphic ceramics by Lucie Rie and Magdalene Odundo, to classics of conceptual fashion by Comme des Garçons, Yohji Yamamoto, and Issey Miyake.

The show is the first in a series of exhibitions in which Hepworth Wakefield’s collection is reinvigorated by the gaze of prominent figures from beyond the art world. “The divisions between creative fields are falling away: artists’ references are coming from an increasingly broad swathe of information and we wanted to reflect that shift,” says Bonacina. “We’re always looking for new ways to tell stories with our collection.”

“Disobedient Bodies: JW Anderson curates the Hepworth Wakefield.” Courtesy of Lewis Ronald.

The intermingling of influences is perfectly embodied in 6a’s design for the show using bolts of leftover cloth from the JW Anderson archive (including a bunny-print corduroy) to create columns and chambers of an intimate, domestic scale. Traditional plinths have been replaced with table-like forms.

A zesty palate-cleanser after the heavy, over-the-top drama of so many recent fashion-related exhibitions, the atmosphere is that of a particularly photogenic (and at times louche and inebriated) cocktail party.

Anderson describes collecting and seeing art as his “personal life,” the thing he does when he’s not designing clothes. It is a preoccupation passed down from his grandfather who remains “an obsessive collector of British ceramics: it rubbed off on me, I knew everything about it.” Since a visit to Tate St Ives he has also been “a huge fan of Barbara Hepworth: I’m obsessed with the vigor of the woman.” Curating an exhibition here is, he says, both “daunting and an honor.”

While never intended as a retrospective, there’s a significant body of Anderson’s own designs in the show, and they come off well. The lighter fingered will twitch, aching, beside his bib-like tubular knits and thermal bonded polyurethane jackets. Famously forward-focused and hitherto dismissive of his designs from seasons past (“it’s so difficult to like what you do, especially if your name’s inside it”), working on the show has given Anderson a new respect for his craft: “I went from someone who did not believe fashion to be an art form to believing it one hundred percent. Fashion is part of our lives and self-expression.”

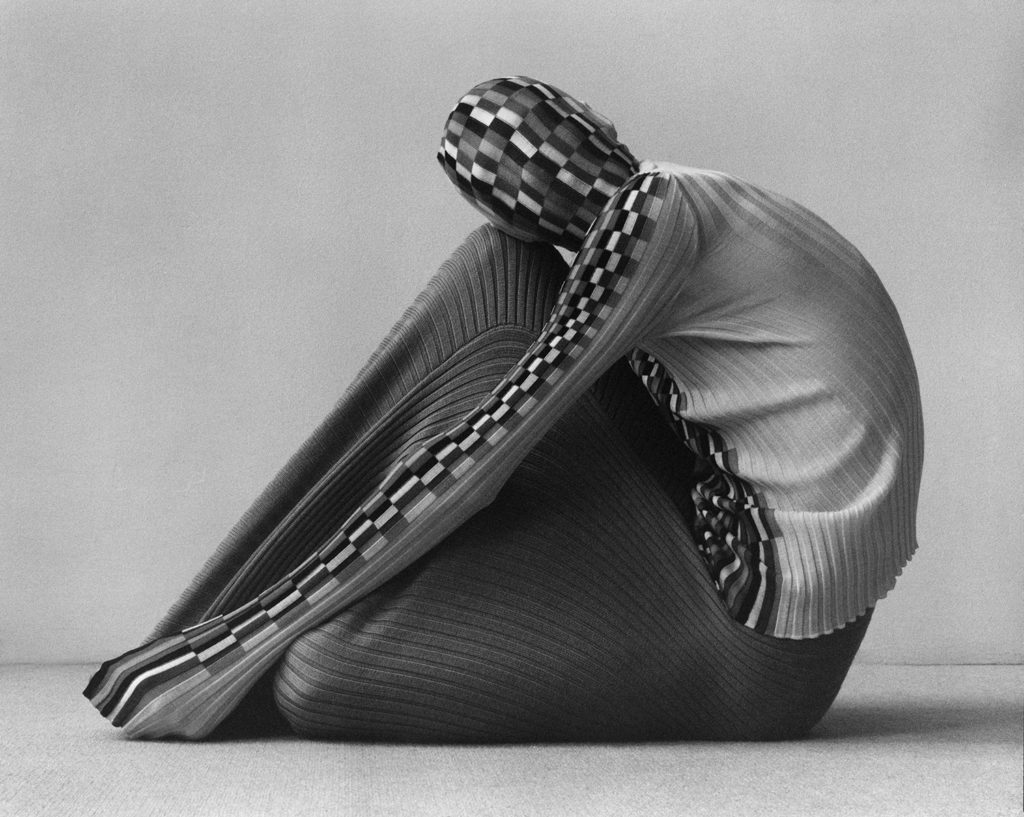

Jamie Hawkesworth, The Thinleys (2015). Photo © Jamie Hawkesworth.

Newfound respect aside, the treatment of garments in “Disobedient Bodies” is winningly irreverent. A Madame Grès gown, of the kind exhibited among the cool of marble statuary at the Musée Bourdelle, is here casually draped over the seat of an Eileen Gray chair, the hem trailing on the floor as if discarded after a heavy night. Helmut Lang’s harnesses are suspended from rods in a line alongside a Cerith Wyn Evans neon. Various chairs are indicated as available for visitors to sit on, including another Eileen Gray and a Gerrit Rietveld.

One quite unexpected highlight comes courtesy the photographer Jamie Hawkesworth, who snapped 123 local schoolchildren wearing exhibits prior to the show. The ethereal shots of little girls in Miyake pleats pale beside the bemused and fractionally apologetic pre-adolescent boys in Elisabeth de Senneville’s plastic and Kraft paper vests.

These are displayed in a room likely to go down a storm with those twelve-and-under. Outsized versions of 28 jumpers from Anderson’s SS 2017 menswear collection are hung from the ceiling like a sweater forest. Visitors are invited to climb inside and create extempore sculptural forms by stretching the knitted tubes with their limbs. Jersey is exploited elsewhere as a sculptural medium, with Anderson stretching a Jean-Paul Gaultier cone dress to echo the form of Henry Moore’s Reclining Figure (1936) in the adjacent gallery. (One of the exhibition’s more exotic sight-lines is afforded by gazing at the Moore across a pair of pointy jersey tits.)

Stretchy knitwear, too, forms the basis of The Thinleys (2015–), an ongoing collab between Anderson and Hawkesworth in which textiles from past collections are wrapped in sculptural arrangements around a male model. When “Disobedient Bodies” was announced last year androgyny was still hot news in the fashion world. Anderson has notably ignored accepted gender norms since the start of his career, so it was generally assumed that it was this rebel territory identified in the show’s title. In truth it is the improvised body-based sculptures of The Thinleys encircling the Moore at the entrance to the show from which Anderson has taken his cues.

If there’s one gripe, it’s that Anderson earning his laurels as an actual curator in an actual gallery will almost certainly rejuvenate the fashion world’s ambition to “curate” anything that doesn’t move, from pompoms to lemon curd.

“Disobedient Bodies,” is on view at the Hepworth Wakefield, from March 18–June 18, 2017