When Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, decided to reevaluate its North American indigenous art collection, uniting objects from its Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, and Yale University Art Gallery for the first time, it looked to the student body to lead the way.

It enlisted a trio of students, two of whom are Native Americans, as the curators. Initially, the students thought that the university “should be hiring someone who is a professional curator and has more time and more knowledge than we do as students,” co-curator Katherine Nova McCleary, who is Little Shell Chippewa-Cree, told Artnet News. “But then we realized that if we didn’t take this opportunity, the show was likely not going to happen.”

In 2015, McCleary and Leah Tamar Shrestinian, who is Armenian and Arab, was Yale’s first participants in a summer internship program for Native American art, a response to student demands for better Native representation on campus. As college juniors, at the gallery’s urging, the two signed on with sophomore Joseph Zordan, who is Bad River Ojibwe, for the ambitious task of putting together an exhibition that presented the university’s holdings of North American indigenous art in an ethical, respectful manner, fully engaging with the Native community in order to best represent its widely varied artistic practices and cultural traditions.

It’s a challenge that has proved a stumbling block for other, larger institutions recently. New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art received plaudits for showing Native American art in its American wing for the first time in “Art of Native America: The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection” and announcing plans to hire its first curator in the field, but the 2018 exhibition was also criticized for its display of funerary objects, and for not consulting more closely with tribal leaders during the planning process. At the Art Institute of Chicago, a planned traveling exhibition, “Worlds Within: Mimbres Pottery of the Ancient Southwest,” was postponed in April over the very same issues.

Attributed to Pablino Lubo Cahuilla), Coiled Basket Tray (1932). Photo courtesy of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History.

But museums shouldn’t let such incidents discourage them, the curators say. If institutions spend too much time “trying to avoid missteps,” said Shrestinian, “that makes museums afraid to even engage with a lot of Indigenous art.” Nevertheless, there remains a lot of work to be done.

US institutions have a troubled historical track record when it comes to indigenous art, colored by centuries of colonialism and violence against Native peoples, forcing them from their lands. Indigenous artifacts were collected with an eye toward preserving a “vanishing” race and put on display, with few distinctions between individual tribes, at anthropological and natural history museums like the Peabody. (In recognition that such an approach was outdated, the Peabody took down its Native American display in 2017.)

“I think museums are having a reckoning over what do with these institutions in the 21st century,” said Zordan. “How do we modernize them? Times are changing, and how do you adapt an institution that hasn’t changed much since its development in the late 19th, early 20th century?”

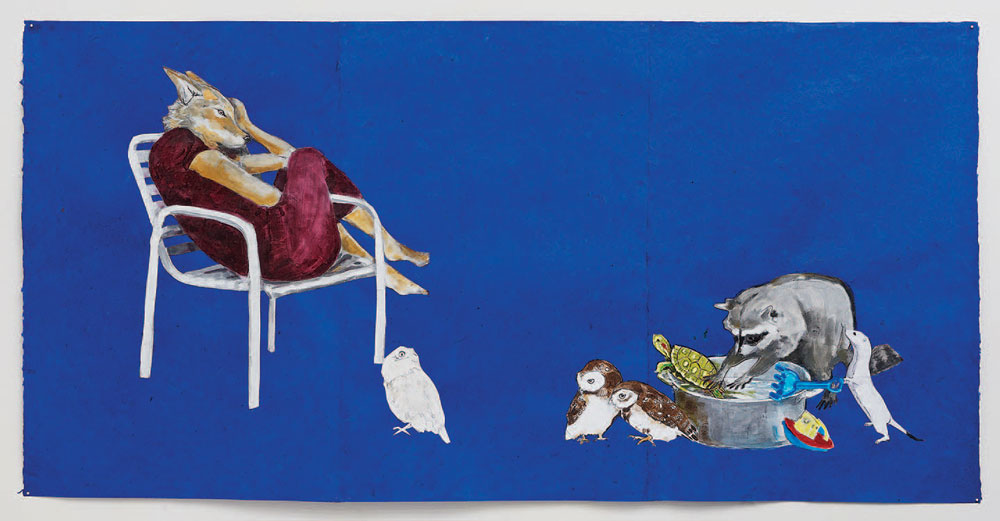

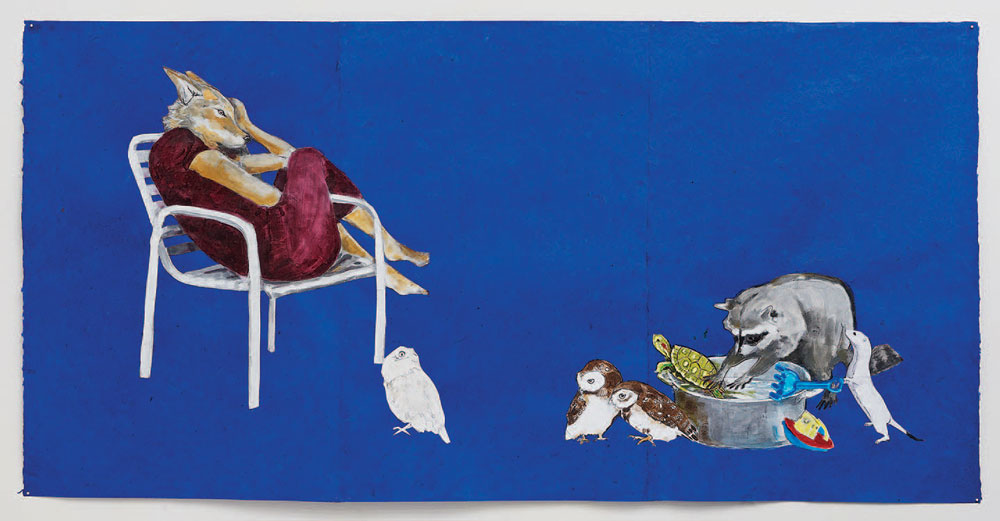

Julie Buffalohead, Indifferent (2017). Photo courtesy of the Yale University Art Gallery.

In organizing “Place, Nations, Generations, Beings: 200 Years of Indigenous North American Art,” the young curators were careful to look to the Native community for guidance.

“It’s important to remember that, yes, we are young people engaging in this work in sometimes new ways, but we’re really relying upon example of people us who have done this work before us,” said McCleary. “There are community institutions and tribal museums that have been thinking about these issues for a very long time—it’s important to not focus just on major institutions that are often settler institutions that have historically been for white people.”

“What we were trying to do was draw from all of this scholarship that Indigenous curators and scholars and other non-Indigenous folks have been writing about since the ’90s, about having advisory councils and including indigenous voices in every step of the process,” said Shrestinian. “The framework for respectfully showing Native art and showing it in an exciting way that can educate people and bring them to appreciate Native art, that’s been set up by Indigenous scholars and curators, and we need to follow that example and collaborate with Native people.”

Yale student curators Joseph Zordan, Leah Tamar Shrestinian, and Katherine Nova McCleary examine objects for the exhibition. Photo by Jessica Smolinski, courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery.

Sometimes, that meant deciding that an object in the university’s collection was not suited for display. That might have been due to the way it was obtained, or how the object would have functioned for Native peoples—or based on feedback from Native advisers.

“The first thing that you have to do is think about who does this object belong to and is this object a being,” said Shrestinian. “To have any of that knowledge and know whether it’s appropriate to share that knowledge, you have to talk to people from that nation, or talk to the artist.”

“There’s no such thing as a hard and fast rule for every object, even sacred objects,” Zordan added. “We had mentors who had experience working on shows such as this one who were able to lead us in the correct direction to approach these works from the sensitive and empathetic position that working with Indigenous art within museums requires.”

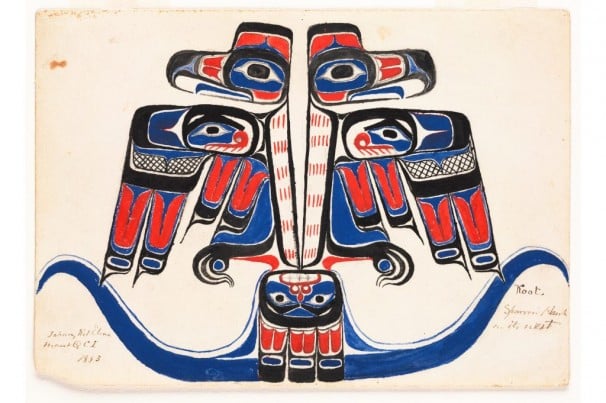

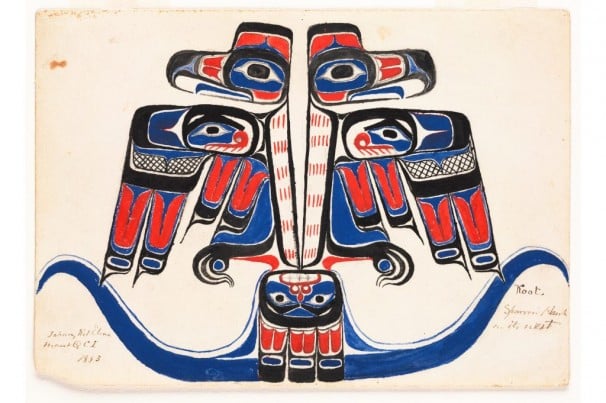

Johnny Kit Elswa, Untitled, (1883). Photo courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Originally slated for the fall of 2018, the exhibition proved such a massive undertaking that it was pushed back a year, after all three curators had graduated—McCleary in May 2018, Shrestinian that December, and Zordan this past May. Completing the show while entering the real world work force was no easy task, and underscores the need for institutions like Yale to create full-time positions for Native American art.

“Museums should be bringing in Indigenous people and scholars, compensating them for their advice, hiring them at institutions, and dedicating resources to the study and presentation of Indigenous art,” said McCleary.

Still, the current show represents an important step forward. “From working on this project,” said Zordan, “I’m hopeful about the willingness of the old guard to accept these new practices and work with us and open the doors of the space.”

See more works from the exhibition below.

Arroh-a-och (Laguna Pueblo) pot (circa early 20th century). Photo courtesy of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History.

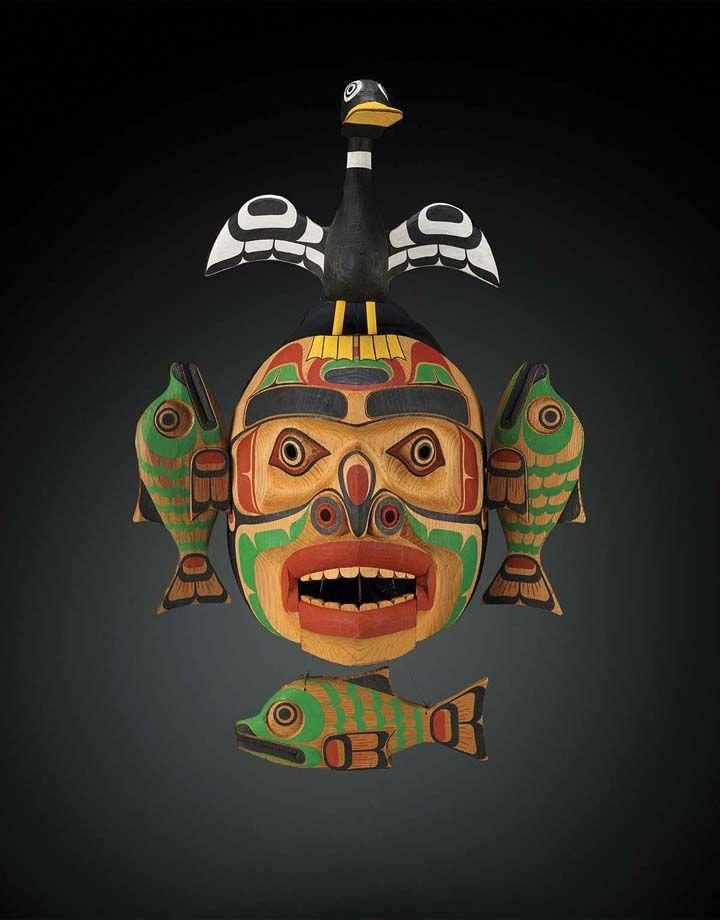

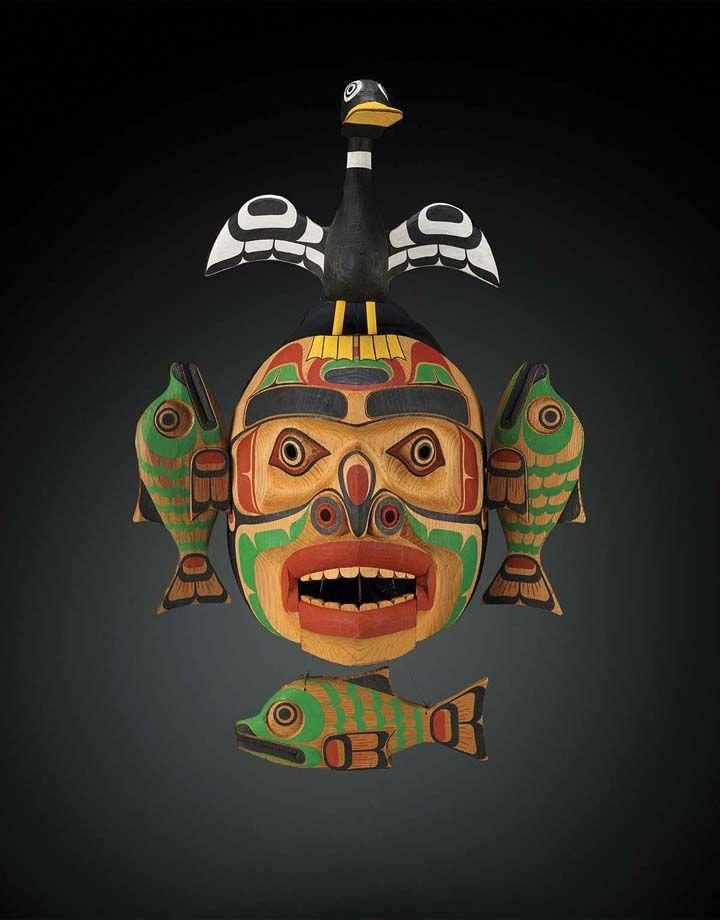

Richard Hunt, Sea Monster Mask (1999). Photo courtesy of Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History.

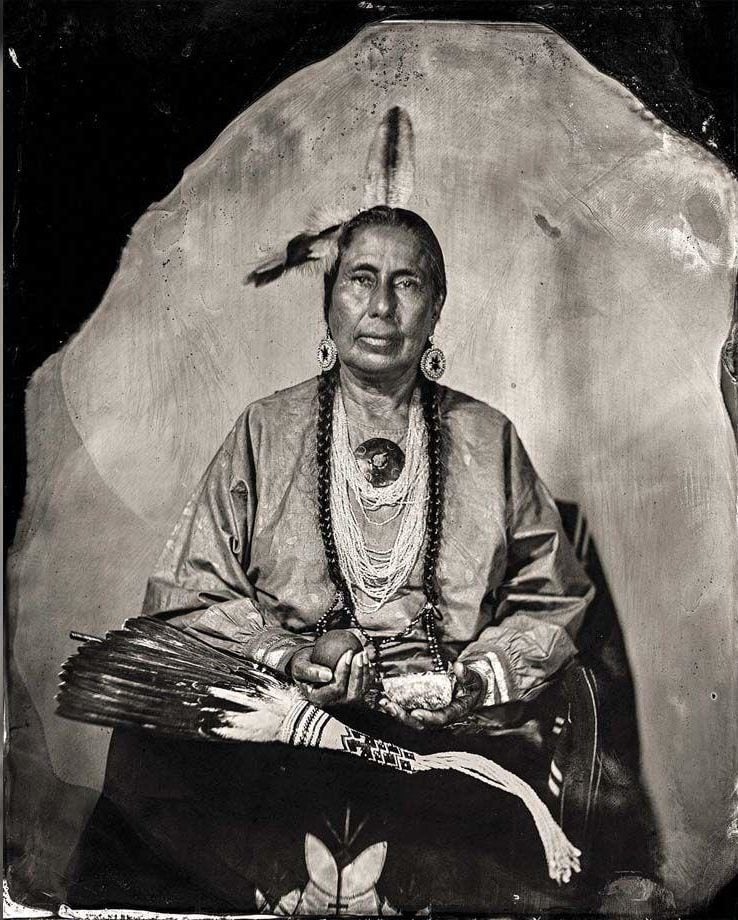

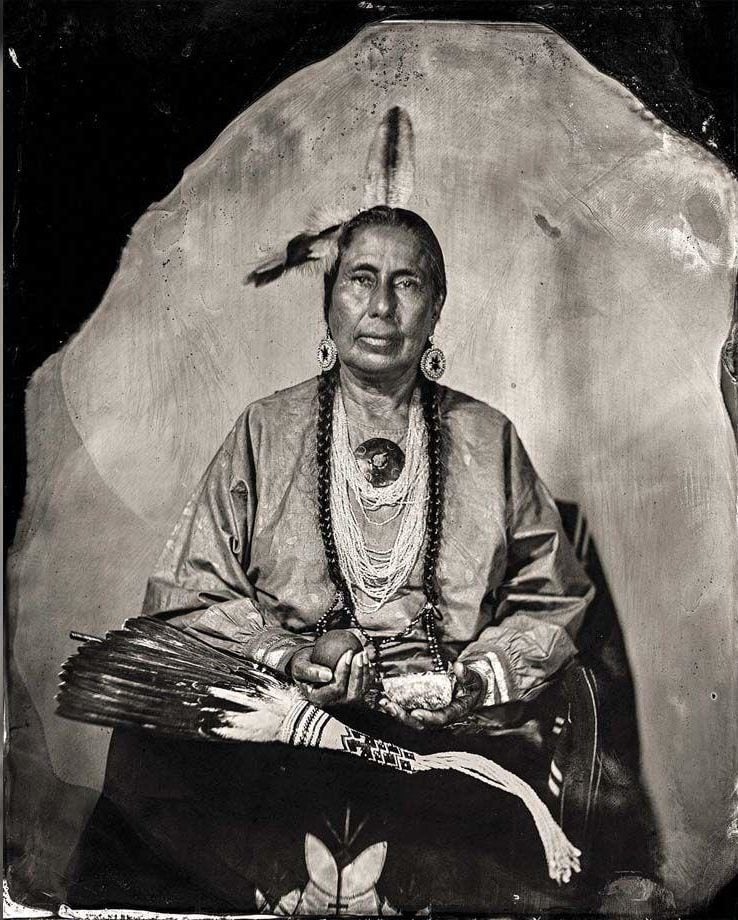

Will Wilson, “Casey Camp Horinek, Citizen Ponca Tribe of Oklahoma, “Zhutni,” Tribal Councilwoman, Leader of Scalp Dance Society, Sundancer, Delegate to UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, Matriarch of Wonderful Family (Grandmother, Companion, Mother, Sister), Defender of Mother Earth (2016). Photo courtesy of Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, ©Will Wilson Artist.

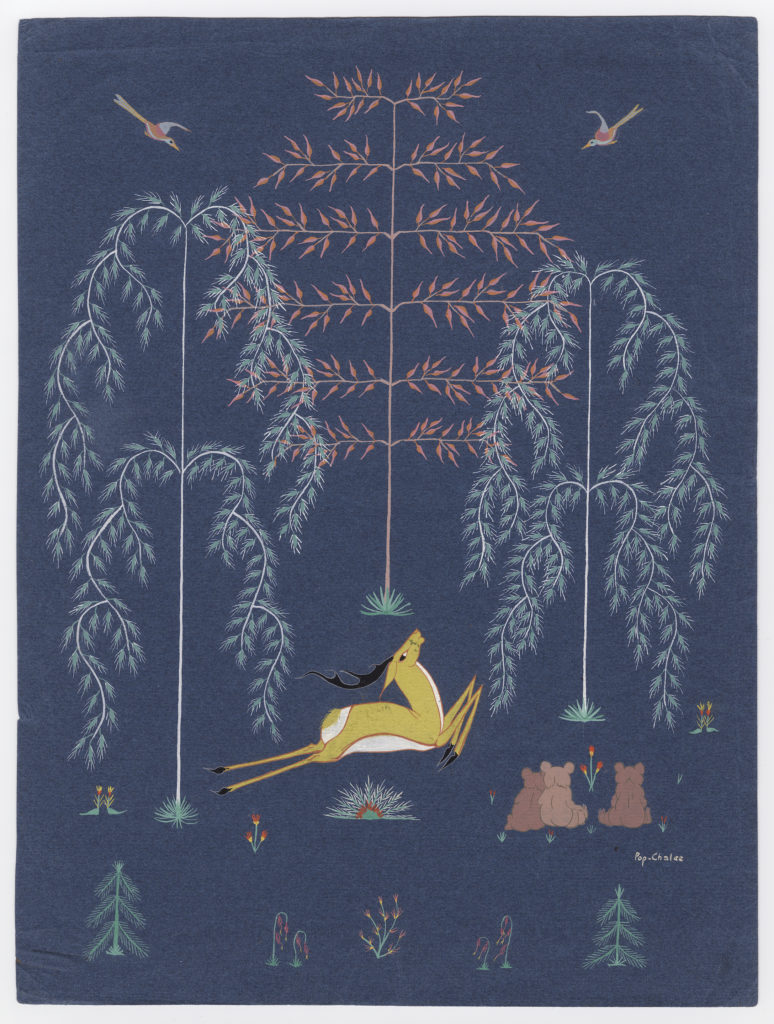

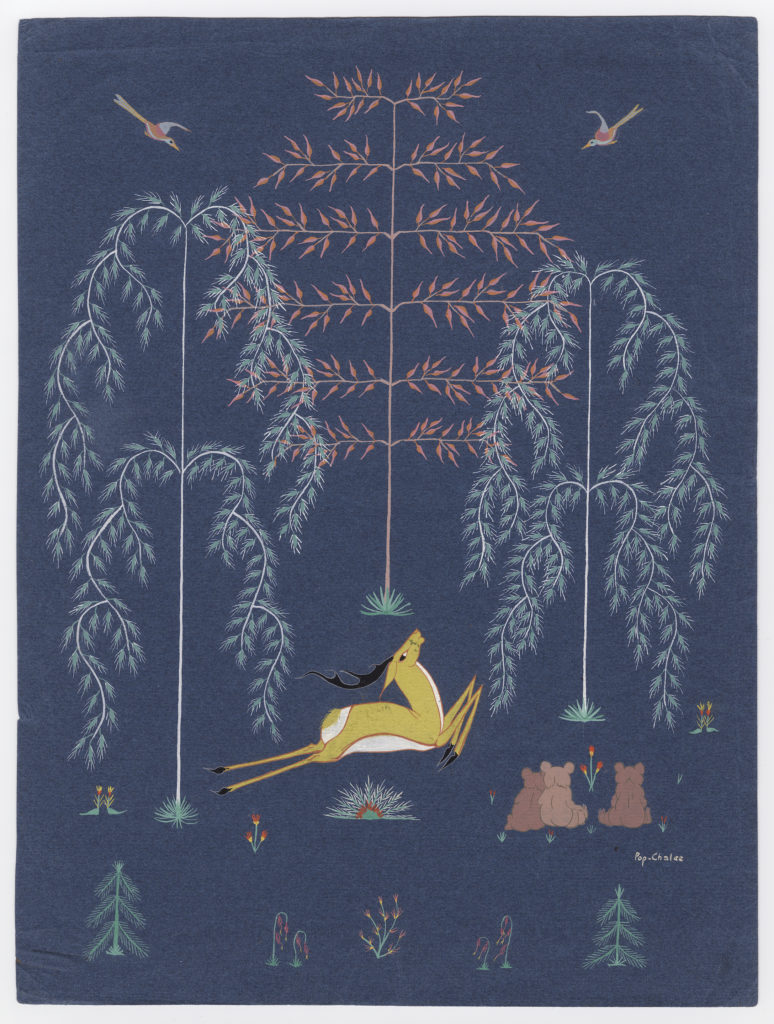

Pop Chalee (Merina Lujan; Taos Pueblo), Deer in a Forest (circa 1930–40). Photo courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

Indigenous moccasins (circa early-to-mid 20th century). Photo courtesy of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History.

Indigenous Quilled Vest by a Dakota artist (circa late 19th century). Photo courtesy of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History.

Azhooningwaon Bandolier Bag by an Anishinaabe artist (circa early 20th century). Photo courtesy of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History.

“Place, Nations, Generations, Beings: 200 Years of Indigenous North American Art” is on view at the Yale University Art Gallery, 1111 Chapel Street at York Street, New Haven, Connecticut, November 1, 2019–June 21, 2020.