On View

Critic Hilton Als’s Latest Show at David Zwirner Takes on the Myth of James Baldwin

The show approaches Baldwin as a complete person—not just as a cultural icon.

The show approaches Baldwin as a complete person—not just as a cultural icon.

Taylor Dafoe

James Baldwin is different things to different people: author, cultural critic, black prophet, queer hero. “God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin,” a new exhibition at David Zwirner curated by writer Hilton Als, looks at the many masks worn by the man—and those that have been forced upon him.

“As a galvanizing humanitarian force, Baldwin is now being claimed as a kind of oracle,” Als explains in the show’s press release. “But by claiming him as such, much gets erased about the great artist in the process, specifically his sexuality and aestheticism, both of which informed his politics.”

This is not Als’s first collaboration with Zwirner. In 2017, he organized the well-received exhibition “Alice Neel, Uptown,” which looked at the painter’s portraits. Following the success of that show, Zwirner approached Als about doing a follow-up.

“When David asked me what I would like to do next… I immediately said Baldwin, for some reasons that were clear to me, and some that only revealed themselves when I began to meet with artists and see their work,” Als said in a walkthrough of the show. “I wanted to give him his body back, to reclaim him for myself and many others as a maverick queer artist that drew some of us to him in the first place because of those things.”

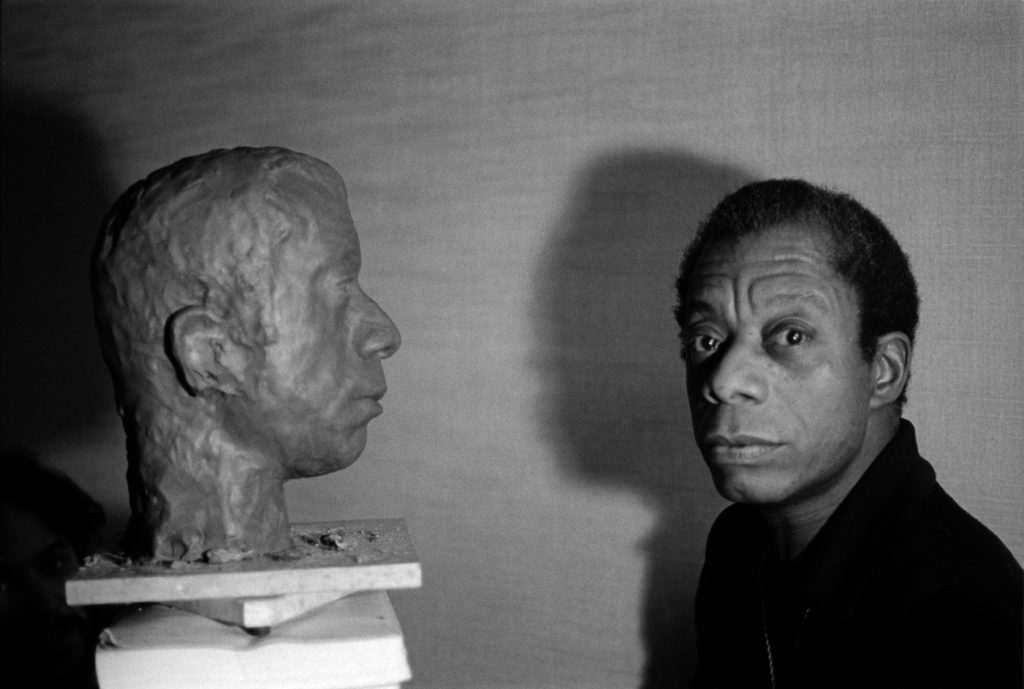

At left, Richard Avedon’s portrait of Baldwin from around 1945. On the right, Marlene Dumas, James Baldwin (2014). Images courtesy of David Zwirner.

The exhibition spans Zwirner’s two adjoining locations on 19th street in New York and is split into two sections, with works by artists including Alvin Baltrop, Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, and James Welling. The first section, “A Walker in the City,” covers Baldwin’s biography; the second, “Colonialism,” looks at how his status as a cultural figure has been used and exploited.

“This is not a group show, but, I hope, a new and valuable way of showing artists who are interested in showing aspects of themselves, their thinking, their politics, their sex, in relation to their times and the history that made them,” Als says. “Baldwin certainly helped make me. And in recent years, I’ve been disturbed by the conversations around his work—a largely heteronormative conversation that elevates the imitator and plunges the white and privileged into a very comforting cold bath laced with guilt and remorse.”

Walking into the gallery, Baldwin’s voice is likely the first thing you will hear. A small record player sits on the floor sounding a recording of the author singing the gospel hymn “Take My Hand, Precious Lord.” Nearby, there is a matte black painting by Glenn Ligon with a passage from Baldwin’s 1953 essay “Stranger in the Village” inscribed in coal dust.

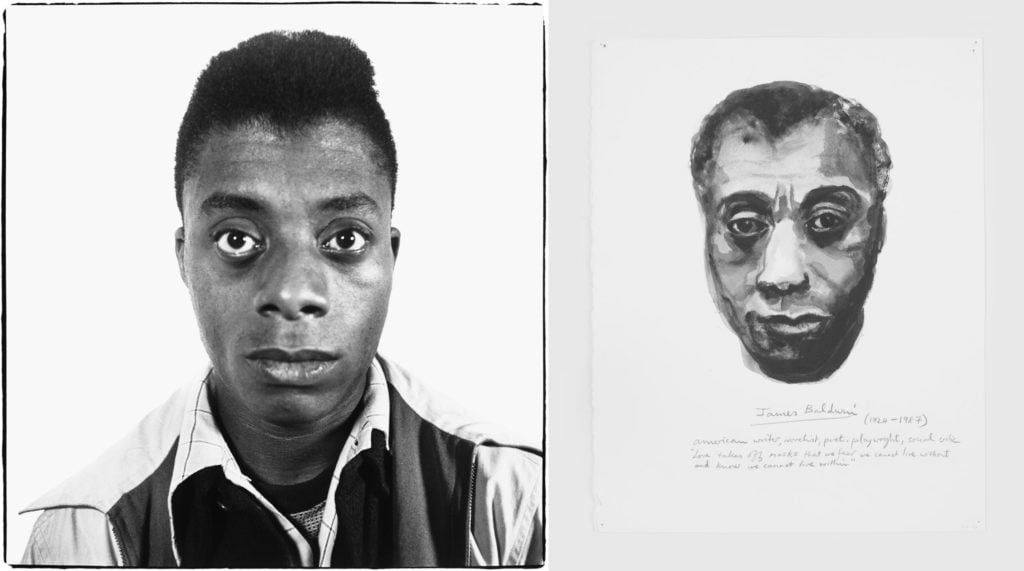

Diane Arbus, A young Negro boy, Washington Square Park, N.Y.C. 1965 (1965). © The Estate of Diane Arbus.

A suite of 14 works on paper made for the show by Marlene Dumas, which are a highlight of the exhibition, hang on an adjoining wall. Taken from her ongoing Great Men series, each features the portrait of an artist who influenced Baldwin—including Beauford Delaney, Langston Hughes, and Marlon Brando—atop a small, biographical blurb. Elsewhere, there’s an installation by Cameron Rowland of salvaged railway parts symbolizing the convict labor used to build railroads throughout the American South.

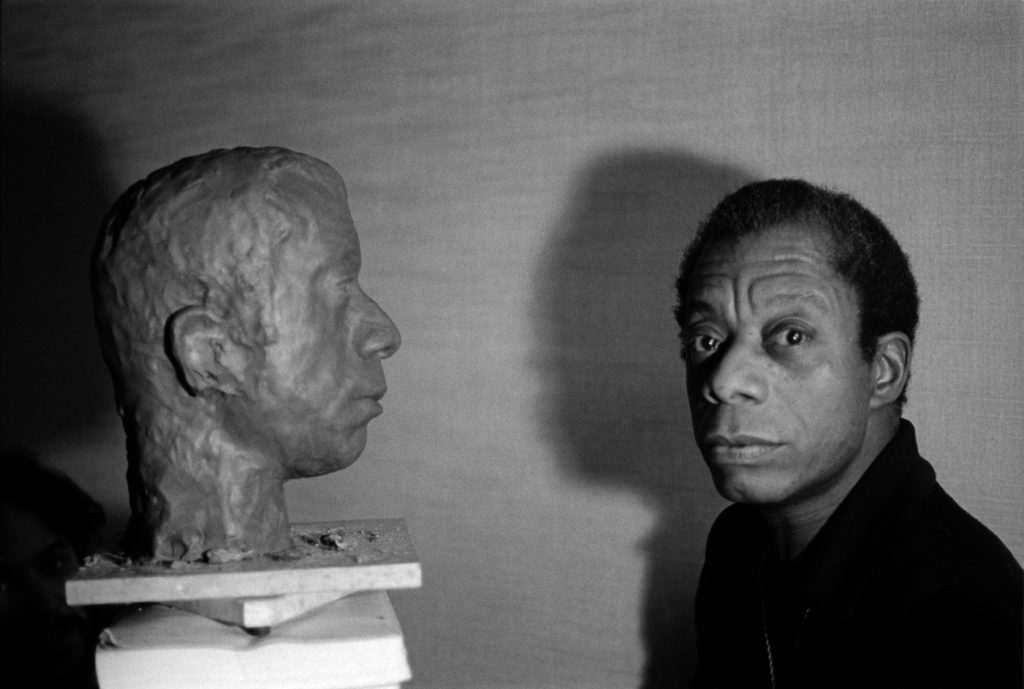

In the hallway between the two galleries, there are black-and-white photos of Baldwin, a bust of the writer by Larry Wolhandler, and a vitrine full of stones that Als collected from Baldwin’s final home in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France. This reflective space opens into the vibrant, second section of the exhibition, which Als calls a “universe of pure metaphor.”

Left: Beauford Delaney, Dark Rapture (James Baldwin) (1941). Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, LLC. Right: Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Nyado: The Thing Around Her Neck (2011). Courtesy of David Zwirner.

This section includes Kara Walker’s 2005 film installation 8 Possible Beginnings or: The Creation of African-America, a Moving Picture by Kara E. Walker, which uses shadow puppets to tell the story of America after slavery, plus works by Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Ja’Tovia Gary, among others.

Throughout the exhibition, Baldwin is everywhere and nowhere. As we learn of his life, we learn how much of it has been told through other people’s art—through portraiture, homage, and appropriation.

“Towards the end of his life, he gave an interview to Richard Goldstein where he said he never felt part of a tribe, a group, but it was his job to witness,” Als says. “I think that meant ultimately recording his feelings and thoughts about women, queers, life, the world. He never got around to all that. It’s my hope that we made the work for him.”

Ja’Tovia Gary, An Ecstatic Experience, film still (2015). Courtesy of David Zwirner.

“God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin” is on view through February 16, 2019 at David Zwirner.