On View

Uh Oh, Mummies Have Taken Over the Museum of Natural History (in a New Show)

Egypt's mummies might be the most famous, but Peru's came first.

Egypt's mummies might be the most famous, but Peru's came first.

Sarah Cascone

Just in time for spring, the mummies have arrived to distract a weary New York public from the exhausting news cycle. Now at the American Museum of Natural History, a new “Mummies” exhibition explores how two civilizations on opposite sides of the globe, ancient Egypt and pre-Columbian Peru, both embraced mummification. Remember Egyptomania? The next big craze could be Peruviomania.

Though mummies are inextricably linked to Egypt, it was Peru’s Chinchorro people who first began mummifying their dead, some 7,000 years ago. The exhibition features a replica of one of the rare clay masks and wigs that would have decorated these Chinchorro mummies.

Other Peruvian cultures would wrap their dead in long rolls of fabric, creating bulky mummy bundles. The museum has created a diorama of a Peruvian pit burial, showing the mummies entombed with personal effects such as ceramics.

Egyptian mummies are, of course, far better known. Egyptomania first swept the West in the nineteenth century, following Napolean’s Egyptian campaign of 1798–1801. The craze returned when Howard Carter discovered King Tut’s tomb in 1922, and again in 1976, when the blockbuster King Tut show began touring the US.

The current exhibition, which originated at the Field Museum in Chicago, includes objects that haven’t been shown publicly since the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893.

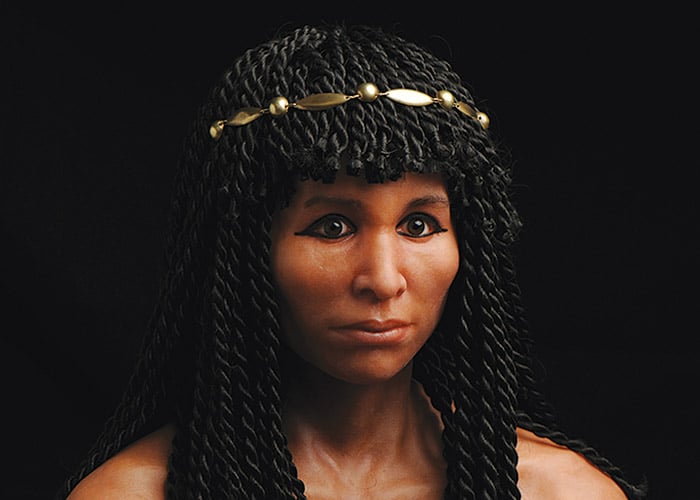

Élisabeth Daynès, Forensic reconstruction of the woman behind the gilded mask (2012). © E. Daynès

One of the show’s highlights is the Gilded Lady, with a face adorned with a thin layer of gold, representing the belief that in the afterlife, the dead would be transformed into the god Osiris. Thanks to CT scanning, experts have determined she likely died in her 40s of tuberculosis, and had curly hair and an overbite. Based on these findings, forensic artist Élisabeth Daynès has even made a sculpture imagining the Gilded Lady as she might have looked in life.

The CT scanner, which is featured in the exhibition, has allowed archaeologists to examine the interior of a mummy without physically unwrapping, and potentially damaging, the specimen. Whereas the Gilded Lady has never been touched, one of the mummies on view was actually accidentally decapitated by archaeologists looking below the bandages, according to the New York Times.

Viewers can explore the use of this digital technology themselves at interactive tables that allow them to virtually unwrap mummies.

“Mummies” is on view at the American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, March 20, 2017–January 7, 2018.