Reviews

The Whitney’s Warhol Show Strives to Spotlight His Human Side. But It’s His Cynicism That Remains Most Surprising

The show presents a very un-Warholian Warhol—and that may be wishful thinking.

![Andy Warhol, Before and After [4] (1962). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from Charles Simon, 71.226 © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York Andy Warhol, Before and After [4] (1962). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from Charles Simon, 71.226 © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2018/11/andy-warhol-before-and-after-1024x742.jpg)

The show presents a very un-Warholian Warhol—and that may be wishful thinking.

![Andy Warhol, Before and After [4] (1962). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from Charles Simon, 71.226 © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York Andy Warhol, Before and After [4] (1962). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from Charles Simon, 71.226 © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2018/11/andy-warhol-before-and-after-1024x742.jpg)

Ben Davis

Why do an Andy Warhol survey right now?

For the Whitney, I assume, that answer is clear-cut: “Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again,” the museum’s substantial new show, is a surefire hit for the tourist-hungry institution. Nevertheless, it is to the credit of the Whitney and this show’s curators—Donna De Salvo, Christie Mitchell, and Mark Loiacono—that it does not come off that way, not exactly.

Nothing would be more classically Warholian than simply trotting out the most familiar Greatest Hits, again. His art is by and large about the allure of the popular; he had a low estimation of public’s hunger for the subtleties of art.

“Why don’t they have someone copy it and send the copy, no one would know the difference,” he once quipped when Mona Lisa toured the US in 1963. That cynical aesthetic philosophy is the subtext of 30 Are Better Than One (1964), his silkscreen indifferently repeating the famed Leonardo in washed out monochrome gray and black.

Andy Warhol, 30 Are Better Than One (1964). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

But “From A to B and Back Again” is not a Warholian Warhol show. It does give you Warhol’s Greatest Hits—your Coca-Colas and Marilyns, your Most Wanted Men and Deaths and Disasters—but it also specifically sets out to give you a more complex figure. It highlights a lot of obscurities and juvenilia and one-offs, and tries to make something out of the less-loved series of the 1970s and ‘80s, by editing them down to just a couple of the most interesting works.

Instead of the Warhol who said “I want to be a machine,” and tended to bleed his own ideas dry through repetition, the impression you get is of relentless artistic soul-searching.

Two portfolios of Andy Warhol’s “Sunset” works (1972). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

The effect, for me, is epitomized by Sunset (1972), a series of silkscreens of identical sunsets in different color combinations, shown midway through the show. Warhol made them on commission for Philip Johnson’s Marquette Hotel in Minneapolis. They strike you as fresh—but this effect depends on how they stand out as a novelty against the mental background of Warhol’s too-familiar works.

Upon consideration, the Sunsets look like just what they literally are: harmlessly hip, mindlessly mass-produced hotel art. (He made over 600.)

Nevertheless, as a museum experience, editing Warhol this way really works. You walk away with the feeling of a less cold, less complacent Warhol, more lovable and lively and human—even, in places, a topically “woke Warhol.”

The question is whether this fresh Warhol myth-making doesn’t also run the risk of falsifying the record, just a bit, in ways that matter.

Installation view of “Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again.” Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Because when we ask “why Warhol now?” there’s a looming, inevitable presence in the background.

The familiar, historic Warhol, the Warhol whose camera-is-always-on persona and endlessly recycled prognostication that “in the future everyone will be famous for 15 minutes” prefigured reality TV fame obsession, the Warhol of commercial appearances and self-promoting Love Boat cameos, the Warhol whose ruthless fixation on celebrity and money and courting the rich provided an arty alibi for Me Generation materialism—we all know what that sounds like, when projected into the politically fraught present, right?

Andy Warhol guest stars on The Love Boat.

It’s not just the stock Everything-Is-Donald-Trump angle that has consumed cultural coverage that makes the press reach for a Trump connection, nor the fact this show’s opening coincided tightly with the all-consuming 2018 midterms.

A pretty straight line connects Warhol’s dubbing himself a “business artist” and Trump’s declaration in the Art of the Deal that “deals are my art form.” In 2009, well into his Apprentice period, Trump’s book Think Like a Champion flatly argued, “I’ve always liked Andy Warhol’s statement that, ‘making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.’”

Despite their evident topicality, Warhol’s 1981 prototypes for a series of images of the Trump Tower are not highlighted in “From A to B and Back Again.” The future president ended up disliking them because they weren’t color coordinated with Angelo Donghia’s decorating scheme for the property.

Warhol was bitter that he never got the money for his work on the Trump Tower works—but the artist’s bruised ego didn’t keep him from agreeing to judge New Jersey Generals cheerleading tryouts held in the basement of the Trump Tower three years later, alongside Trump’s first wife, Ivana (though he did contrive to show up late).

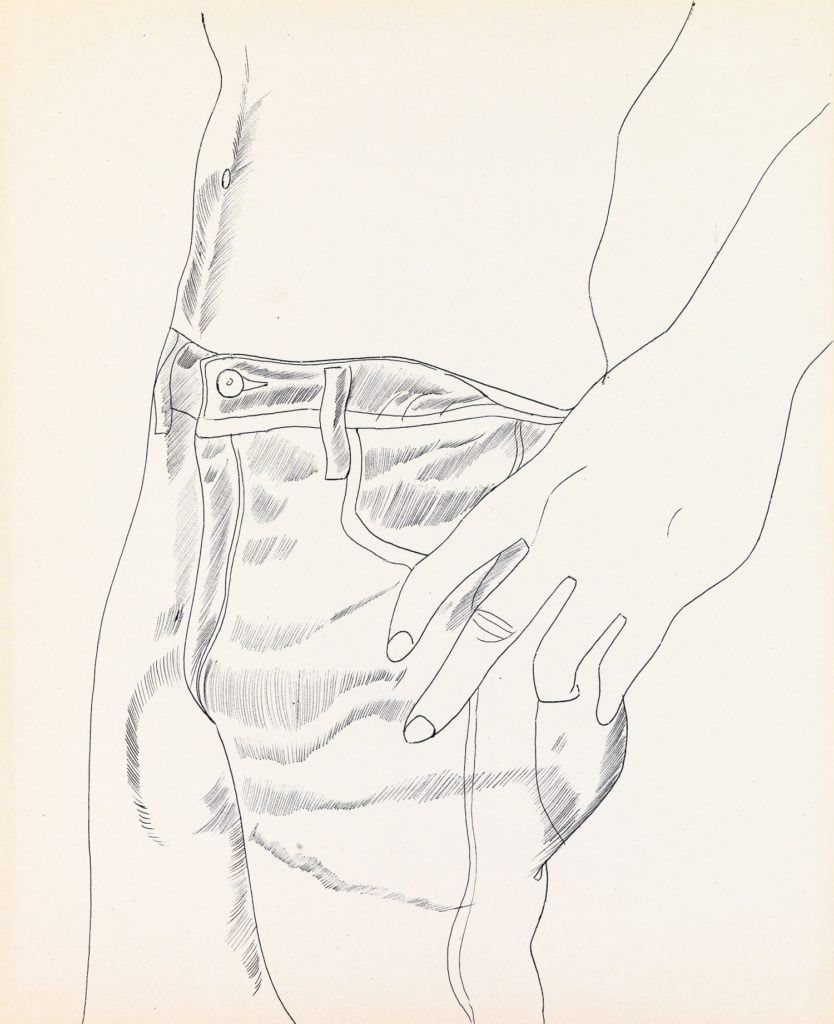

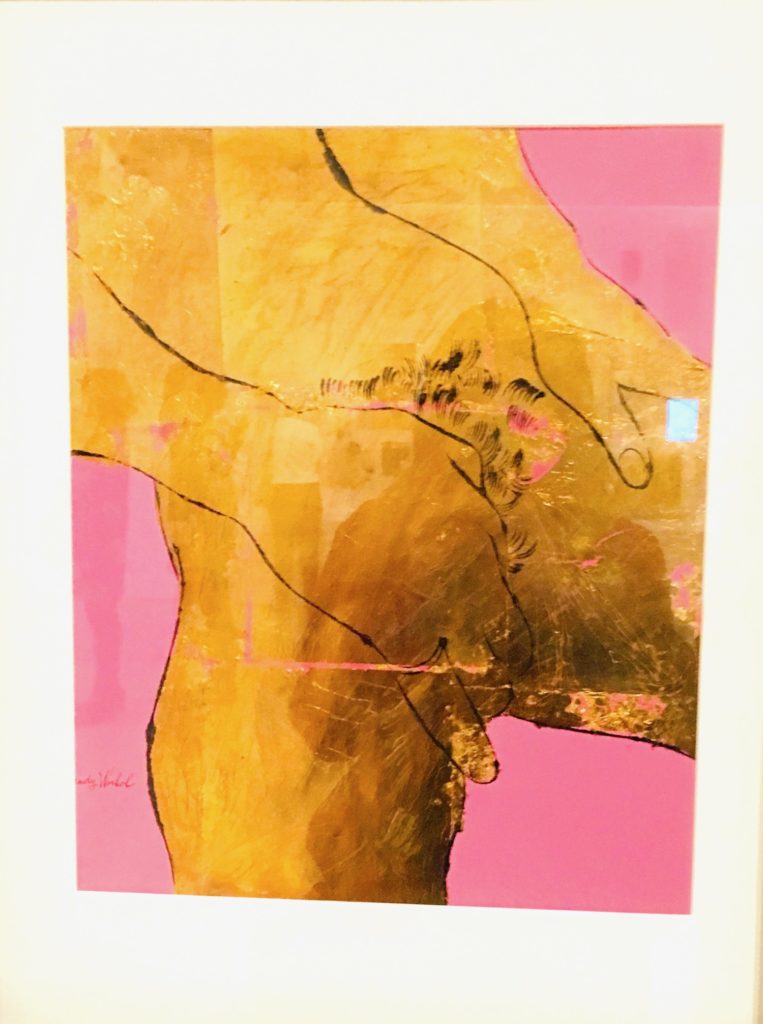

The progressive case for Warhol lays mainly in the visibility he gave to alternative lifestyles and gay identity, and the Whitney presses hard on this facet of his work, offering a relatively rare look at his personal early drawings, full of explicitly gay imagery, and late ultra-graphic pornographic silkscreens.

Andy Warhol, Untitled (Hand in Pocket) (ca. 1956). Collection of Mathew Wolf © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York

“If you want to know all about Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it,” Warhol famously said.

Nevertheless it is not too hard to see this poker-faced superficiality as a defense mechanism: If you are out to neutralize any sense of emotional depth, it may be because you are afraid of what will happen if people see your depths. And Warhol was a gay man and practicing Catholic who came up in the pre-Stonewall era.

Today, it may be easy to forget how truly rare and generative Warhol’s Factory was in opening up a space for queer identity to take on positive public dimensions (indeed, well before the word “queer” had a positive meaning). Even a slightly older generation of gay male artists, like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, felt the need to distance themselves.

Andy Warhol, Male Nude (ca. 1957). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

As artist Charles Atlas would recall, “[W]hen Andy Warhol came on the scene, they thought he was too swish…. The social world really was not that tolerant of openly gay people. The gay world was a separate world.”

If you want a laugh and to get a sense of just how dangerously deviant Warhol seemed, go read his FBI file. J. Edgar Hoover had the headline-making artist tailed, and in 1968 even sent a pair of G-Men to report back on a screening of Lonesome Cowboys at the San Francisco International Film Festival. “There was no plot to the film and no character development throughout,” they reported back to their boss soberly in the resulting memo. “It was rather a remotely connected series of scenes which depicted situations of sexual relationships of homosexual and heterosexual nature.”

But then again, J. Edgar Hoover was a monster, and he had files on everyone.

And it is necessary to note that Warhol’s construction of what has been called a “subaltern counterpublic” in the Factory, with its constellation of Superstars, was just one version of queer identity, albeit one whose dazzle became culturally dominant. And it was one that not everyone loved. For instance, the artist Hélio Oiticica, also gay and fleeing Brazil’s dictatorship for the relative liberation of New York, found Warhol’s Factory distasteful, “raising marginal activity to a bourgeois level.”

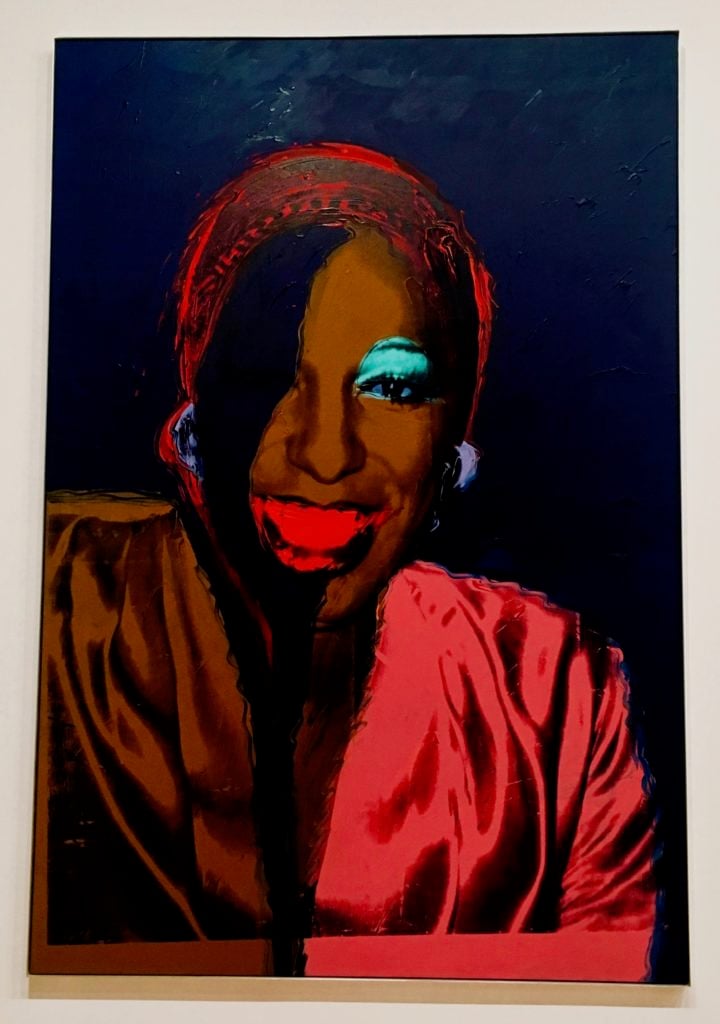

In the current Whitney show, the ultimate symbol of Warhol’s uneasy status as a champion of sexual identities is probably the colorful portraits taken from his late “Ladies and Gentlemen” series, of 1975, which focused on crossdressers and transwomen of color. It’s been seen before, but it’s new to me, and the Whitney’s show probably gives it a new visibility as part of Warhol’s legacy and legend.

Andy Warhol, Ladies and Gentlemen (Wilhelmina Ross) (1975). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

The largest work features Wilhelmina Ross, a performer and actress (she had a bit part in the Lynn Redgrave film the Happy Hooker), who was the most photographed model for the series. Among those pictured in a cluster of smaller works from the “Ladies and Gentlemen” series, hung nearby, is Marsha P. Johnson, the activist and co-founder of S.T.A.R. (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries), an all-around righteous figure who participated directly in the battle at the Stonewall Inn, which gave birth to the modern gay liberation movement.

Their presence in “Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again” seems to stand as a symbol that Warhol wasn’t quite as nihilistically disengaged as his legend has it—that there are depths that you haven’t seen.

Then again, the story of “Ladies and Gentlemen” as a series is actually quite fraught. It was the result of Warhol’s all-time biggest commission—$900,000—from his Italian dealer Luciano Anselmino, who suggested the theme: African American and Latino drag queens, explicitly and cruelly intended to focus on “funny-looking ones.” The title, also suggested by Anselmino, is an unsavory joke.

![Images from Andy Warhol's "Ladies and Gentlemen" series (1975), depicting [clockwise from left] Alphanso Panell, Ivette and Lurdes, Marsha P. Johnson and Helen/Harry Morales. Image courtesy Ben Davis.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2018/11/warhol-ladies-and-gentlemen-2.jpeg)

Images from Andy Warhol’s “Ladies and Gentlemen” series (1975), depicting [clockwise from left] Alphanso Panell, Ivette and Lurdes, Marsha P. Johnson and Helen/Harry Morales. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

The Whitney catalogue also features a witheringly skeptical essay about the series by artist Glenn Ligon. “That Warhol even used models he found outside of the Factory, instead of using the drag queens and trans women he already knew, was a cost-saving measure,” Ligon argues, “for he was certain that the models for ‘Ladies and Gentlemen’ wouldn’t return to ask him for more money every time a painting using their image was sold.”

The series was shown in Ferrara, Italy, and evidently enthusiastically received by the Italian press. From the beginning of Warhol’s career, European critics had the strange tendency to view his Pop art through the lens of Marxist critique—and “Ladies and Gentlemen” only continued the quixotic misreading.

Thus, Warhol the businessman looking to service a hunger for exotic marginality was read as… a bold social critic of ruthless American values.

“The left-wing Italian art critics went wild, writing that Andy Warhol had exposed the cruel racism inherent in the American capitalist system, which left poor black and Hispanic boys no choice but to prostitute themselves as transvestites,” Bob Colacello, the Warhol associate who helped find the models at a trans bar called the Gilded Grape, near Times Square, would claim.

The catalogue described the portrait subjects as having the “grimace of the victim”—though, it must be said that the subjects themselves look joyful, and it is Warhol’s unusually aggressive treatment that stands in for the “grimace.” Ross has a strange crescent of black eclipsing one side of her face, becoming a rivulet of black down her front, as if the ink were running off her.

In any case, “Ladies and Gentlemen” was received not as a celebration of its subjects’ proud identities—the sitters were anonymous, their identities left for art historians to track down much later when a former associate from an underground drag theater, the Hot Peaches, recognized Ross’s image by chance at a Gagosian show in the late ’90s. Marsha P. Johnson’s accomplishments as an activist and organizer were beside the point. The “Ladies and Gentlemen” series was read in its time as a representation of degradation.

And the upshot is that a presence that seems in the Whitney show to cut against Warhol’s mercenary reputation actually probably ratifies it.

Visitors watching films in “Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again.” Image courtesy Ben Davis.

“Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again” succeeds aesthetically by constructing a more appealing, less cynical Warhol for the present. Still, one hopes, intellectually, that it provides the occasion to look frankly and critically at the cynicism as well as the glamour. Both have had a long afterlife. Both are key to understanding the world that Warhol leaves behind.

“Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again” is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, through March 12, 2019.