Art & Exhibitions

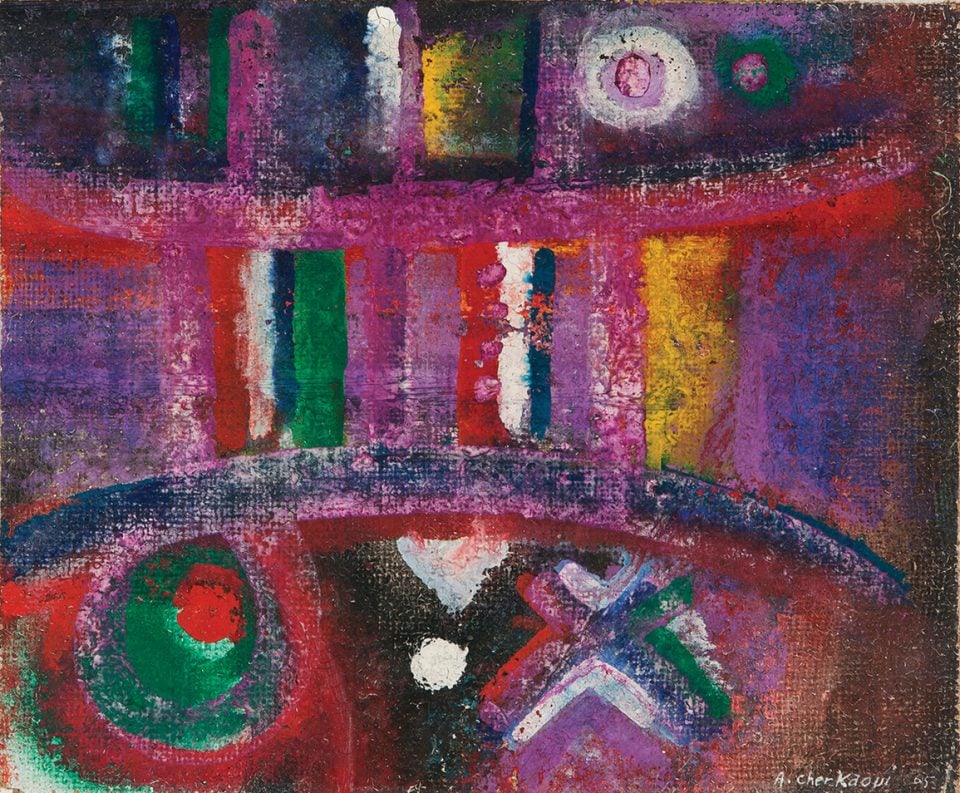

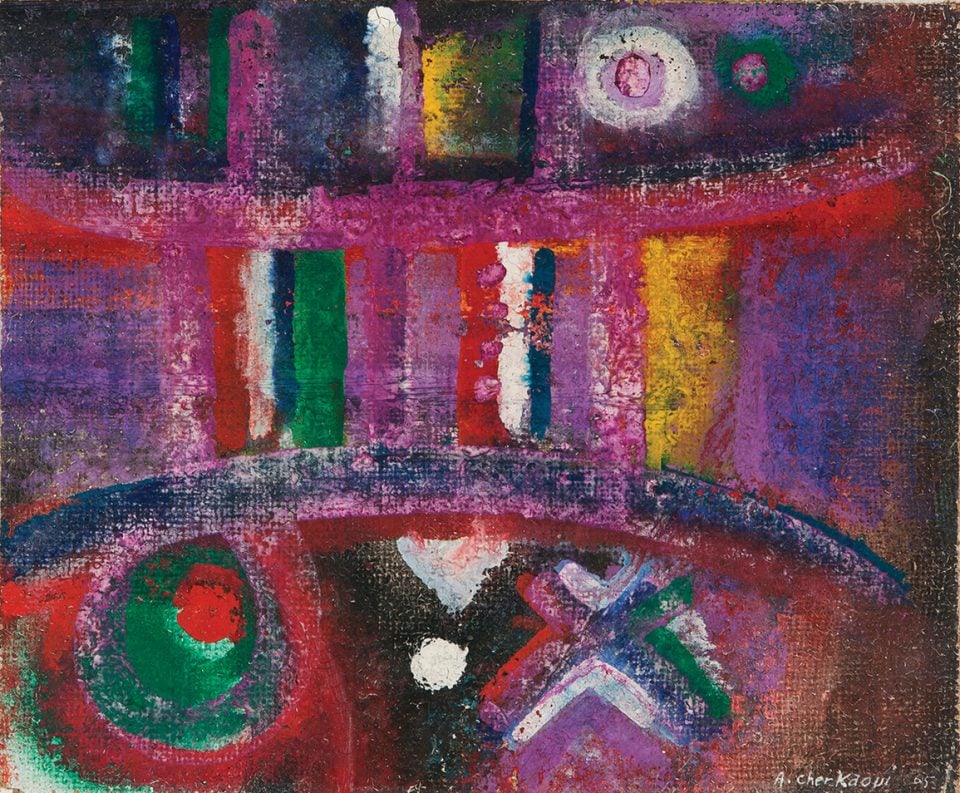

A Groundbreaking New Survey of Abstract Painting From the Arab World Adds a Vibrant Chapter to Art History

The curators of “Taking Shape: Abstraction From the Arab World, 1950s–1980s” explain the mission behind the show.

The curators of “Taking Shape: Abstraction From the Arab World, 1950s–1980s” explain the mission behind the show.

Taylor Dafoe

The middle of the 20th century was a tumultuous time for the 22 countries of the Arab world. It was a period of decolonization and industrialization, of war and mass-migration. It saw the rise of socialism, the global oil boom, and the formation of new nations.

“Because many of these countries were entering the world arena as independent nations and young nation-states, one of their primary objectives was to begin defining themselves as being distinct peoples. A good way to do that is through culture and through art,” says Suheyla Takesh, a co-curator of “Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s–1980s” at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery.

As its name suggests, the show charts the rise of non-figurative art produced in—and by artists from—Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, and other countries of North Africa, West Asia, and the Arab diaspora. Nearly 90 paintings, sculptures, and other works populate the exhibition’s walls and floor, all of which were taken from the collection of the Barjeel Art Foundation, an independent organization dedicated to Arab art located in Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Installation image of “Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s–1980s.” Photo: Nicholas Papananias, Courtesy of the Grey Art Gallery, New York University.

“Many art schools and collectives were being formed during this time as people tried to come up with what it means to be, say, an Iraqi artist or an Egyptian artist,” Takesh adds. “Much of this time period found artists going back to their local histories and heritage to revive innovative ways to create a new, site-specific modernism.”

Takesh, the sole curator at the foundation, teamed up with the Grey’s director, Lynn Gumpert, to realize “Taking Shape.” The ambitious topic hadn’t been tackled in detail before and necessitated a great deal of new scholarship, starting more than two-and-a-half years prior to the opening. (A hefty catalogue edited by Gumpert and Takesh was published alongside the exhibition.)

Despite the considerable investment of resources required, Gumpert says, such work is vital now as we rewrite our collective understanding of modernism through a global—not strictly Western—lens.

“We all were trained in Western art history; there was no other art history for us to turn to,” says the Grey director. “That’s finally starting to break down and there are other histories being written. We hope that this show adds to that momentum.”

Saliba Douaihy, Untitled (c. 1960–1969). Courtesy of the Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah, UAE.

Founded around the personal collection of sultan Sooud Al Qassemi, a member of the Sharjah ruling family known for his globe-spanning efforts promoting Arab art and culture, the Barjeel Art Foundation counts more than 1,000 artworks in its holdings.

“We were lucky that the body of work was so diverse,” says Takesh. “It forced us to look into the differing, more specific histories as well as the artists’ personal histories and their development as individuals.”

Indeed, a wide variety of approaches to abstraction is represented in “Taking Shape,” inspired by everything from mathematics, geometry, and spiritualism to Arabic calligraphy and Islamic decorative patterns. Often, formal techniques can be traced back to regional heritage.

Installation image of “Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s–1980s.” Photo: Nicholas Papananias, Courtesy of the Grey Art Gallery, New York University.

For instance, cuneiform was a big influence for Iraqi artists, while traditional amazigh patterns can be seen throughout art made in North Africa. For other artists represented in the exhibition, the turn to abstraction was a political gesture, intended to contradict the popularity of social realism that came with the rise of communism and socialism.

The deconstruction of the Arabic alphabet is another theme that courses throughout the show, as is the desert landscape and its monochromatic pallet.

There’s a temptation to read the developments in these countries against the well-charted evolution of abstraction in Euro-American art, from Wassily Kandinsky to Picabia, Picasso, Pollack, and so on. The comparison may be problematic insofar as it defers to Western art as the dominant narrative. Yet at the same time, Gumpert notes, many artists in the Arab world were very much aware of developments in modern art elsewhere.

Etel Adnan, Autumn in Yosemite Valley (1963–1964). Courtesy of the Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah, UAE.

“One of the things we found was that many of these artists themselves were aware of [the cross-cultural conversation] because they attended Western-style art academies,” she explains. Many artists sought inspiration from both Europe and their own country’s heritage of architecture, textiles, and other applied arts.

“It just so happens that a lot of their sources are already non-representational,” adds Takesh. “So the work that came out is what people trained in Western art history would call abstract, even though some artists have said that abstraction as such wasn’t their goal. The goal was making work that was relevant to their context, which a lot of the time happened to be non-representational.”

Ultimately, “Taking Shape” shows that art history itself is abstract. It’s as hard to define as any painting on the walls of the Grey.

“Art history likes to make categories that are nice movements, one following and reacting to the other,” says Gumpert, “but the art itself is much messier.”

Installation image of “Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s–1980s.” Photo: Nicholas Papananias, Courtesy of the Grey Art Gallery, New York University.

“Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s–1980s” is on view through April 4, 2020 at New York University’s Grey Art Gallery.