Reviews

In ‘The White Album,’ Arthur Jafa Invents a New Film Language to Take on the Clichés of Empathy

In his striking follow-up to 'Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death,' Jafa trains his lens squarely on the subject of whiteness.

In his striking follow-up to 'Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death,' Jafa trains his lens squarely on the subject of whiteness.

Colony Little

Music has long played a central role in Arthur Jafa’s artistic practice. His latest video is no different: The White Album, at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, combines a pair of eclectic musical tracks with a series of provocative video segments that tackle thorny issues around race and violence.

But while this new piece can be seen as a conceptual extension of his previous work, Jafa also retools his approach to interrogate the dialogue that has swirled around it. The result is a powerful rethinking of the relationship between making art about race and the audience’s reception of that work.

In Jafa’s 2016 video, Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death, music did the emotional heavy lifting, with a rapid-fire barrage of images of black life carried by Kanye West’s gospel-laced vocals in “Ultralight Beam.” But the overwhelmingly affirmative responses to the piece forced Jafa to reassess its timing, messaging, and emotional impact in this new work: The White Album sets out to confront the crutches white viewers rely on when in search of absolution.

To the artist, the near universal response among viewers to Love Is the Message felt stilted. “People were getting this eight-minute epiphany…,” he explained to BAMPFA curator Apsara DiQuinzio. “[E]ven when people said, ‘Oh I cried,’ the very cynical part of my brain suspected some kind of arrested empathy with regard to the experience of black folk.”

Beyond the emotional connection to the music, the safe distance between viewers and the diverse ideas around blackness remained. (Ironically, the compulsion to truncate the title to Love is the Message serves as a perfect symbol of this elimination of the more challenging meanings of the work.)

Arthur Jafa, Still from The White Album (2018). Photo courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/Rome; commissioned by the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA). © Arthur Jafa, 2018

Jafa operates as the visual equivalent of a DJ, building a succession of images that take viewers on an emotional journey, like songs in a set. In The White Album, Jafa not only shifts the gaze to white people, he also deploys a different editing process, eschewing the quick edits of his previous work, challenging viewers to take a long, unflinching look at whiteness.

In the 40-minute video, Jafa sequences a series of sustained, emotionally charged videos, interspersing them with extreme close-ups of various men and women. This editing effect has its own musical reference behind it: Jafa cites as an inspiration legendary house DJ Larry Levan, known for his extended remixes and record sets that are interspersed with raw acapella interludes. By manipulating songs with pitch controls and effects, Levan creates something entirely new. In The White Album, the rawness of the close-ups, scrutinizing facial features, function like Levan’s acapella interludes between the lengthy video segments.

“[T]his is pure sequencing, being a selector,” Jafa told DiQuinzio, explaining the importance of Levan as an inspiration. “They transform the actual—not just the experience of the thing but the thing itself in some fundamental way—just by contextual resequencing.” The White Album’s carefully chosen progression of videos plays an important role in creating a dialogue on whiteness that’s uncomfortable and hard to digest.

Arthur Jafa, Still from The White Album (2018). Photo courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/Rome; commissioned by the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA). © Arthur Jafa, 2018

In one video, a young blonde woman talks into her camera, attempting to muse on racism. She starts to unravel a string of platitudes that begins with, “I am the furthest person from being racist.” To black and brown people, these familiar phrases are often red flags for gaslighting. She quickly followed her opening salvo with the oft-used, “Some of my best friends are…”

As she stumbles through one over-used, empathetic cliché after another, she starts to shift the responsibility of racism back to people of color, directing us to own up to our own expressions of bias. Jafa then cuts away to a close-up of actor Val Kilmer, pictured in the video for the electronic musician Oneohtrix Point Never’s 2016, “Animals.” Wearing a red Nike track suit while sitting on the edge of a bed, Kilmer’s image here evokes sheer exhaustion at the young woman’s musings.

Jafa then switches to an Instagram video of the rapper Plies, known for his hilarious Instagram rants that are filmed sitting in his car, wearing a snapback and gold grills. He also is talking directly into the camera, and the sequencing makes it appear as if he’s in conversation with the young woman. “You wanna argue,” he says. “I can’t argue with you. Nooooo. Look at you. You mad, you big mad.”

The woman’s attempts to shift the conversation away from her own biases are thwarted by this redirect—encouraging viewers to interrogate their own feelings about the exchange.

Jafa’s artful juxtaposition of video segments mirrors the meticulously curated images that form his voluminous library of “visual notebooks,” which are also available for viewing on select days and via appointment at BAMPFA as part of the current show. For over 20 years, Jafa has fastidiously compiled these binders into a visual diary that draws connections between the concepts he addresses in his work. There’s a curious randomness among the photos he selects: an African mask may be placed next to a picture of a surfer on one page; an image of an album cover may rest next to an advertisement on the next.

Some of the notebook images of lynchings and the scarred back of a slave repeat themselves with disturbing regularity. Looking through the albums at the museum left me with the same haunted feeling that I experienced watching The White Album.

In the video, Jafa offers moments of comic relief including a viral video of cyber goths dancing in the “Mask Off” challenge (a 2017 meme featuring clips of various people performing to a popular track by Future) and a spotlight-stealing marching band member caught sporting a delightfully evil grin. Yet these sparks of levity exist to give way to more sinister segments that foreshadow the insidious, intense violence of real-life, tragic events.

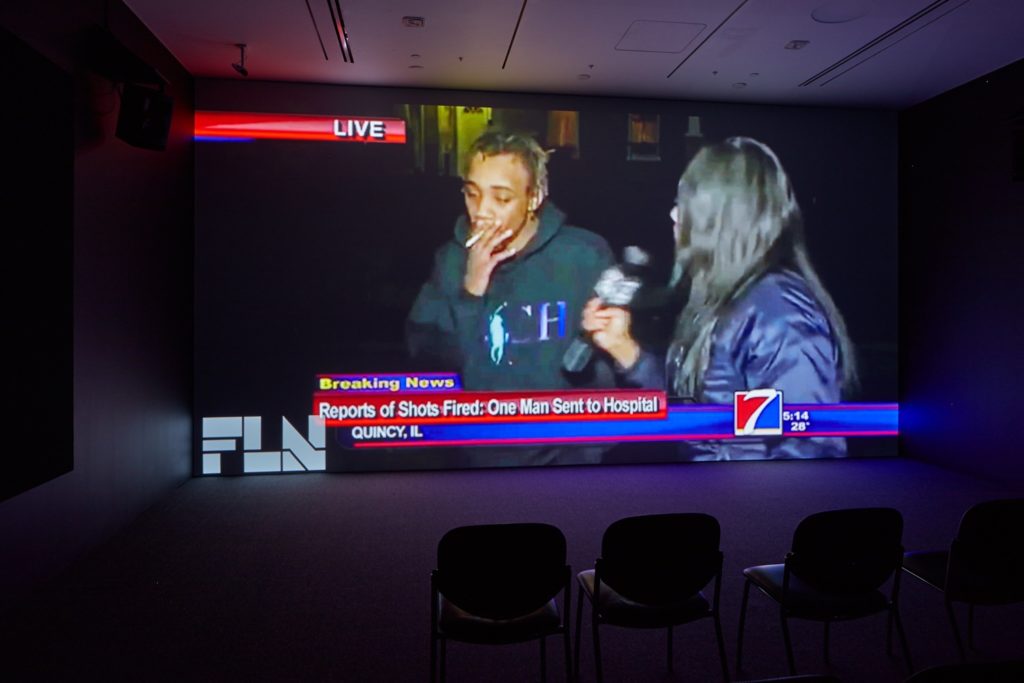

Arthur Jafa, Still from The White Album (2018). Photo courtesy the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York/Rome; commissioned by the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA). © Arthur Jafa, 2018

Most memorably, Iggy Pop’s somber vocals and his eerily rendered digitized image from the 2017 music video for “The Pure and the Damned” precede chilling black-and-white surveillance footage of a car pulling into a parking lot. As the identity of the driver remains obscured by the camera angle, the suspense intensifies as viewers are left waiting for what feels like an eternity. The driver slowly comes into view as the camera captures him calmly walking through the unlocked door of a building. (To preserve the emotional impact of the piece for future museum visitors, I am intentionally leaving the identity of the man unknown.)

At this point, most viewers will be aware of what happens behind that closed door without being expressly shown. Instead, Jafa forces them to quietly sit with the horror conjured from their memory as he cuts away to another video.

Minutes later, he brings viewers back to the surveillance video. The man calmly exits the building, gets into his car, and drives away. This time image and memory perform the emotional heavy lifting as viewers must simply sit with their knowledge of this unspeakable tragedy, without musical catharsis. The artist refuses to allow the resilience of gospel pop to let them off the hook.

The inability to retreat into the safe place of detachment is what sets The White Album apart from Love is the Message. And its timing couldn’t be more relevant as weekly reminders show us that our unwillingness to address racism continues to perpetuate it.

As I sat through the video, only a handful of people remained through the entire 40 minutes. Being confronted with a mirror was perhaps too uncomfortable for some to endure.

“Arthur Jafa / MATRIX 272” is on view at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, through March 24, 2019.

Colony Little is the creator of Culture Shock Art.