Mona who? These works of art may not be quite as famous as Leonardo’s prim portrait, but they’re worth a visit when you go back to the Louvre, which happily reopens on July 6.

The Law Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon (ca. 1792–1750 BC). Courtesy of the Louvre.

What to know: In this seven-foot-tall basalt stele, the earliest and most thorough record of laws is set literally in stone. King Hammurabi of Babylon, the ruler of Mesopotamia, set out these 282 laws (written in the Akkadian language and in cuneiform script) in the 18th century BC. The dictates govern all manner of conduct (and consequences), from familial matters, to questions of business, to laws governing militias.

The stele offers a model of a sovereign ruler’s jurisdiction, and also catalogues the territories and towns within the king’s realm, serving as a kind of written map for his domain. The writing itself is a literary relic that formed the basis of learning for scribes, who studied it for hundreds of years after it was made.

Where to find it: Ground floor, Richelieu wing, room 227

Aphrodite, known as the Venus de Milo

ca. 100 BC

The Venus de Milo (ca. 100 BC). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

What to know: This elegant sculpture was discovered in 1820 on the island of Melos and presented to Louis XVIII, who gifted it to the Louvre, where it was received with great fanfare. The goddess of love is depicted in the Hellenistic style, marked by a spiral composition: the slight twist in her torso results in a sinuous S curve, and the smooth features of her skin juxtapose with the drapery at her hips.

The statue’s missing arms have been a subject of curiosity for many scholars, some of whom say she may have once held an object—an apple or mirror, perhaps—alluding to the ephemerality of beauty. The woman’s serene face and sensual body have long been held as a standard of beauty.

Where to find it: Ground floor, Sully wing, room 346

Fra Angelico, The Coronation of the Virgin (ca. 1430-32). Courtesy of the Louvre.

What to know: The Coronation was a popular theme in the 13th century, and Fra Angelico’s retable is thought to have been commissioned by the Gaddi family for a monastery near Florence. (A second depiction of this event by the artist is at the Uffizi in Florence.)

Arranged in a pyramidal form, the composition is organized around a linear perspective. The predella at the bottom of the work shows individual scenes preceding the main event.

Where to find it: First floor, Denon wing, room 708

Albrecht Dürer, Portrait of the Artist Holding a Thistle (1493). Courtesy wikimedia commons.

What to know: At the ripe age of 22, Albrecht Dürer had finished his apprenticeship in his native town of Nuremberg, and set off on a tour of Germany, along the way committing his own image to canvas in what is believed to be one of the first examples of a Western self-portrait in which the figure is the sole subject.

In the painting, Dürer presents himself as a sophisticated man, turned three-quarters to the viewer in a jaunty red cap that matches the trim and seams of his blouson. This is not the first time Dürer depicted himself, and in this more mature rendering, his neck is strong, his chest is broadened, and his hands are those of a grown man. Scholars have opined that the thistle in his hand alludes either to his impending marriage to Agnes Frey (the plant’s name in German is mannstreu, which also translates to “husband’s fidelity”), or that it may be a nod to Jesus’s crown of thorns.

Where to find it: Second floor, Richelieu wing, room 809

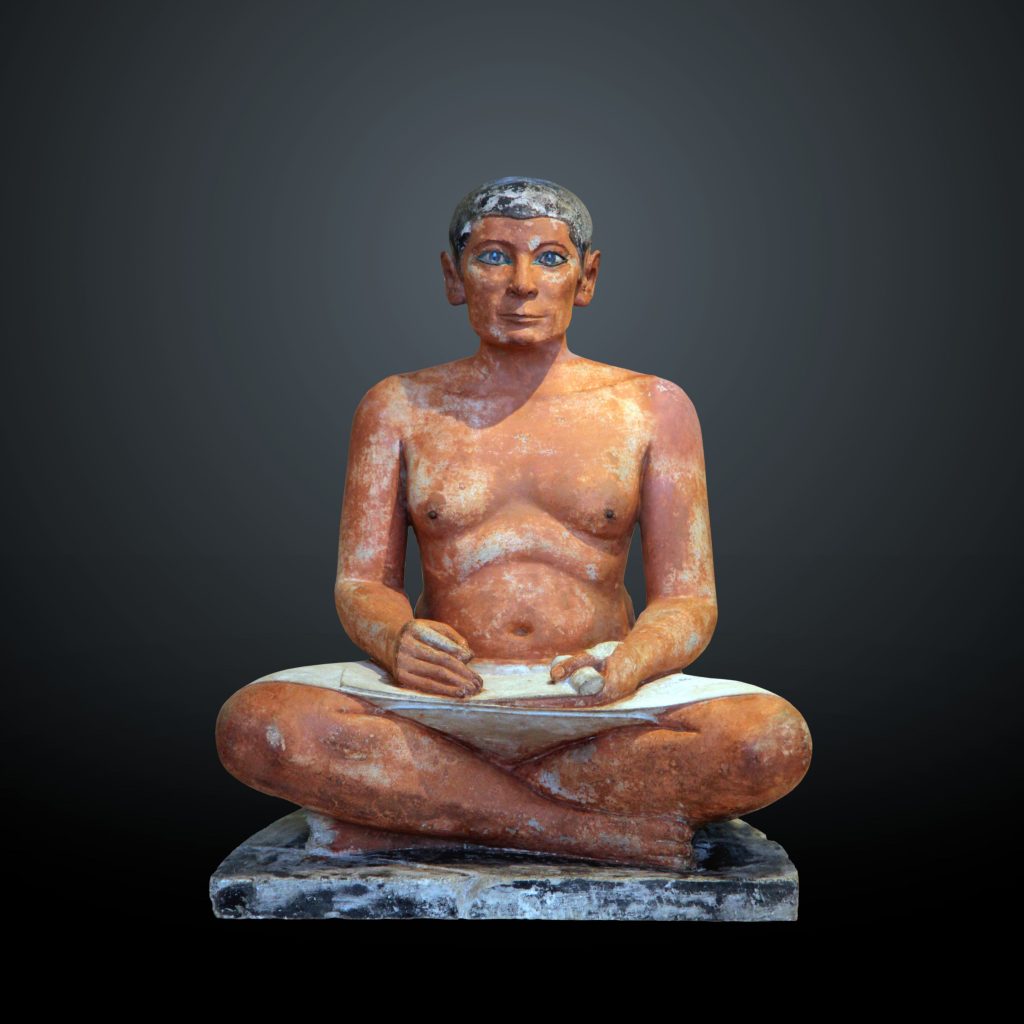

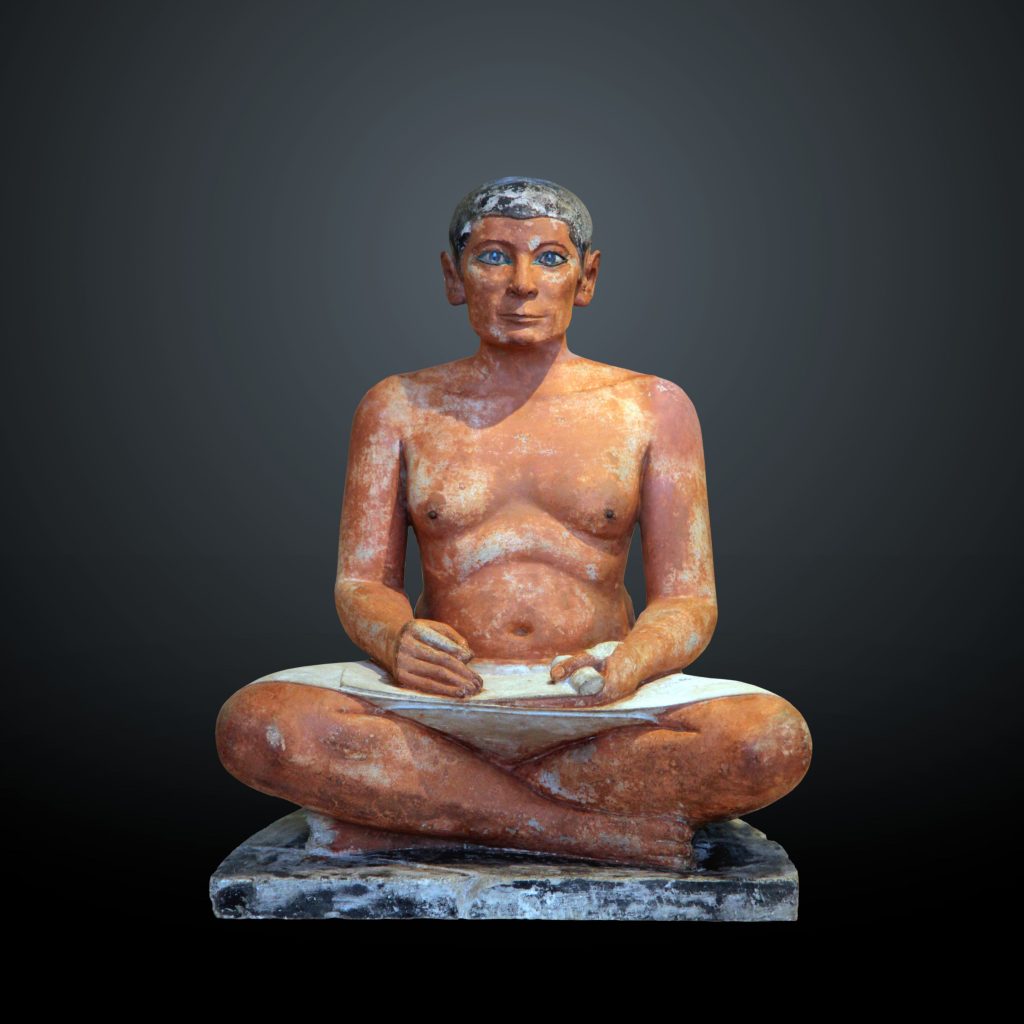

Seated Scribe (ca. 2600–2350 BC). Courtesy of the Louvre.

What to know: This nameless man is one of the most enduring images of Egyptian art, as much for his anonymity as for his impressive figure. Known only by his posture, the seated scribe is a man of indeterminate age. Clad in a white sheath from the waist down, the scribe has a roll of parchment on his lap, and though he may have held a brush at one time, the implement is long gone. Though based on similar works, this statue may have originally been placed atop a large base. But that too is gone, leaving only the semicircular slab on which he rests.

The man’s close-cropped haircut and symmetrical ears frame a piercing set of eyes, punctuated by black brows painted on. The inlaid eyes are made from white magnesite holding a polished piece crystal for the iris, with two copper clips welded onto the back to hold them in place. Strong cheekbones and a chiseled jaw give no more indication to the man’s state of mind, though his slightly sagging paunch gives him a restful aura.

Where to find it: First floor, Sully wing, room 635, vitrine 10

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Pilgrimage to the Isle of Cythera (1717). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

What to know: When Watteau submitted this landscape for entry to the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, it immediately prompted the invention of a whole new term, fêtes galantes, to describe the idyll of a lively court scene. Cythera is the island where Venus was born, and a sculpture of her is set to one side, as if she is giving her blessing to the amorous couples lounging about in long gowns and pastel-colored finery. The lovers are immersed in one another, while groups of cherubs flit over the golden horizon.

The painting’s title indicates that the group are about to set off for a voyage to the island, but as many have noted, the couples are already on the island and seem to be about to depart. This ambiguity was never clarified by Watteau himself. Still, the painting remains an archetypal work of the Rococo period, characterized by rosy, soft colors, imaginative landscapes, and an overall sweetness.

Where to find it: Second floor, Sully wing, room 917

Théodore Géricault, The Raft of the Medusa (1819). Courtesy of the Louvre.

What to know: In 1816, a French Royal Navy ship called the Medusa set out to colonize Senegal, helmed by an incompetent commanding officer. In short order, the ship hit a sandbank and was irreparably damaged. With too few lifeboats, 150 people were left to fend for themselves, cobbling together a raft and desperately drifting across the ocean. Only 10 people survived after more than two weeks at sea.

This is the subject that Géricault chose, after hearing the story from two survivors of the wreck, and the painting became an emblem of Romanticism. The scene is filled with drama in the roiling sea, broken bodies, heavy clouds, and a tragic figure desperately waving a makeshift flag toward the horizon in the hopes of rescue.

Where to find it: First floor, Denon wing, room 700