Reviews

I Saw Burning Man Art in a Museum While Not on Drugs, and Here’s What Happened

A visit to "No Spectators" in DC prompts some thoughts on the value of popular art.

A visit to "No Spectators" in DC prompts some thoughts on the value of popular art.

Ben Davis

I have a friend who got married at Burning Man. I have a friend who has just one rule when she dates: No Burners.

That about sums up the public image of the big festival in the Black Rock Desert, currently on through Labor Day Weekend. As for me, I have been before, and I liked it (with caveats).

You could fill the playa with the think pieces about Burning Man written over the course of the last two decades (or more: Bruce Sterling’s Wired cover story came out in 1996!) But the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery in Washington, DC, has a show, “No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man,” up through next year, so now is a fine time to take stock of its aesthetic output and its place in the US art universe.

If you go into the galleries, you will find some historical photos, some timelines on Burning Man’s growth into the cultural behemoth it is today, and some vintage flyers and other dusty artifacts. You will even see, displayed in glass jars, the preserved ashes of previous men Burned.

Display of Burning Man ashes in “No Spectators.” Image courtesy Ben Davis.

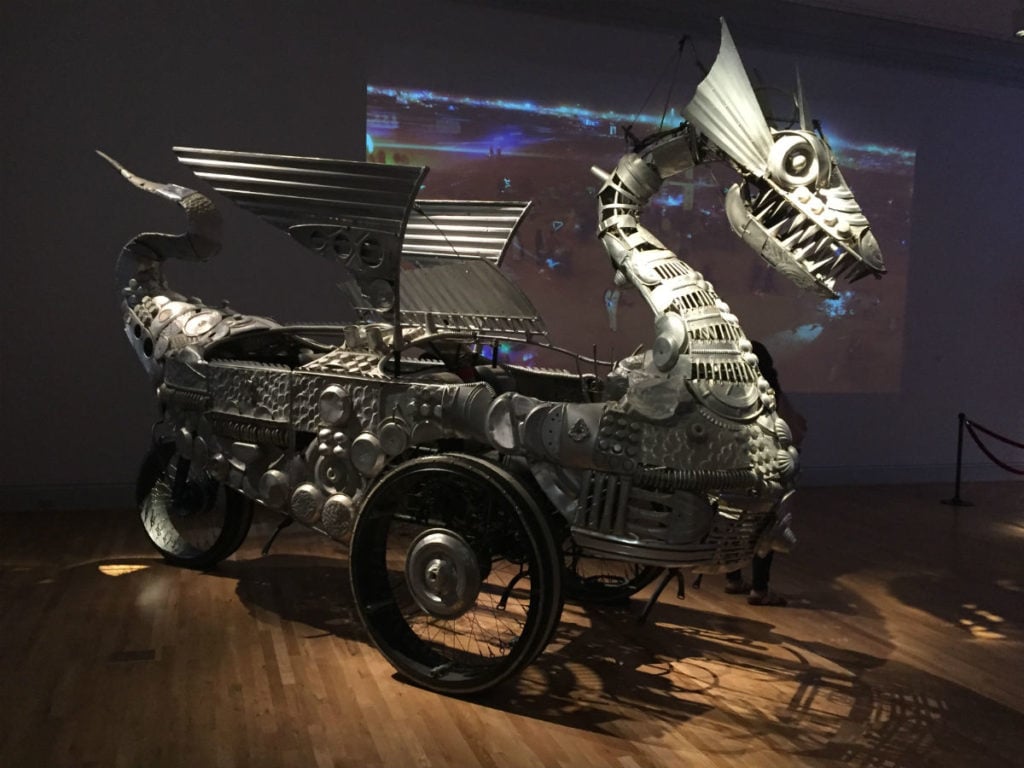

But the centerpiece is, after all, the Art of Burning Man. And so will find this cool metal dragon-boat car, courtesy Duane Flatmo.

Duane Flatmo, Tin Pan Dragon. Photo courtesy Ben Davis.

You will pass beneath Marco Cochrane’s brobdingnagian, pirouetting sculpture of a nude woman.

Marco Cochrane, Truth Is Beauty (2017), Renwick Gallery, Photo by Ron Blunt. Image courtesy Renwick Gallery.

You will find yourself in front of Hybycozo’s latticed lanterns, casting intricate geometric shadow patterns all around.

Gallery view of Hybycozo. Photo by Ron Blunt. Image courtesy Renwick Gallery.

You might bask in Christopher Schardt‘s psychedelic grotto of floating animations and colored light.

Christopher Schardt, Nova. Photo by Ron Blunt. Image courtesy Renwick Gallery.

The Burning Man style is not full of nuance that rewards later interpretation and reflection. It’s big and colorful and tactile. The art is diverting to peruse—and probably about as interesting to read a description of as hearing someone tell you about a dream or a drug trip.

It is easy to dismiss Burning Man art very quickly as being wholly inappropriate for any kind of serious treatment. Yet you might note how it echoes certain themes in recent contemporary art, making it interesting to figure out where it really fits in.

“Relational aesthetics” is well out of vogue as a concept now, in favor of the even more dogoodery forms of “social practice.” But it was not that long ago that injecting social connection and interactive experience into the art context was considered quasi-avant-garde.

The acts of communally eating Thai food (Rirkrit Tiravanija) or going down a slide (Carsten Höller) or basking beneath a huge fake sun (Olafur Eliasson) were all reframed, in that moment, as some kind of resistance to art’s aura of isolated contemplation and elitist pretension.

Each of these gestures (communal giving of food, ingeniously reworked playground attractions, sensuous light shows) directly mirror things that are very much a part of Burning Man culture.

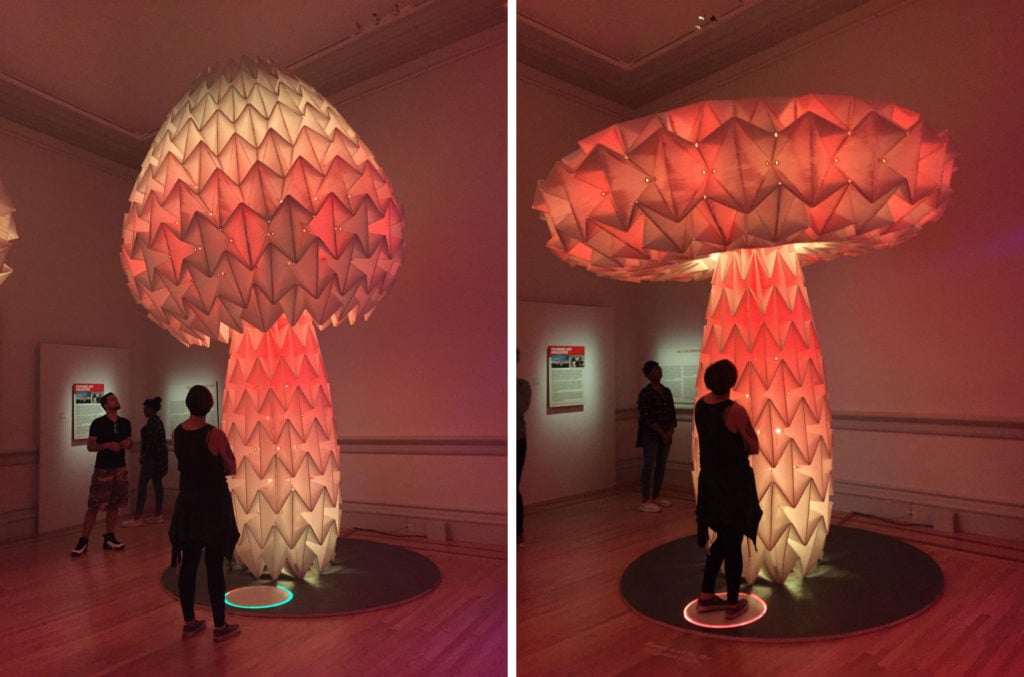

Images of the FoldHaus Collective’s Shrumen Lumen (2016), in transformation. Photo courtesy Ben Davis.

On the other hand, an installation in “No Spectators” like Shrumen Lumen, by the FoldHaus collective—a grove of over-sized, multicolored mushrooms that actually stretch or contract when you stand on a pressure sensor in front of them—really does look as if one of Höller’s installations of giant Alice in Wonderland mushrooms met up with one of Eliasson’s prismatic lamp sculptures for a weekend in the desert.

Even the most fun-fair-like “relational aesthetics” stuff, however, took a lot of its energy from the contrast it provided with its museum origins; the effect of such works depended on playing knowingly off of the coldness and otherwise deadening experience of the gallery. The art in “No Spectators,” by contrast, feels like it is showing you a transplanted, tamer version of a kind of experience that really draws its energy from elsewhere.

Some of “No Spectators” is very bad; some is a lot of fun. Strange to say, the feature that the Burning Man art has going for it, as opposed to all that “relational aesthetics” stuff, is its almost utter lack of good taste.

Like, this is not the fake intellectualized “bad taste” of trying to be weird or offbeat; this is the actual bad taste of not being very self-conscious about what is cool.

Why is that a compliment? Personally, what I found most exciting about the actual Burning Man experience was not the ambient hedonism, the “Radical Self-Expression” part. It was the sense of immediacy; that you weren’t documenting it or judging what was going on from a gaze outside its own weird headspace.

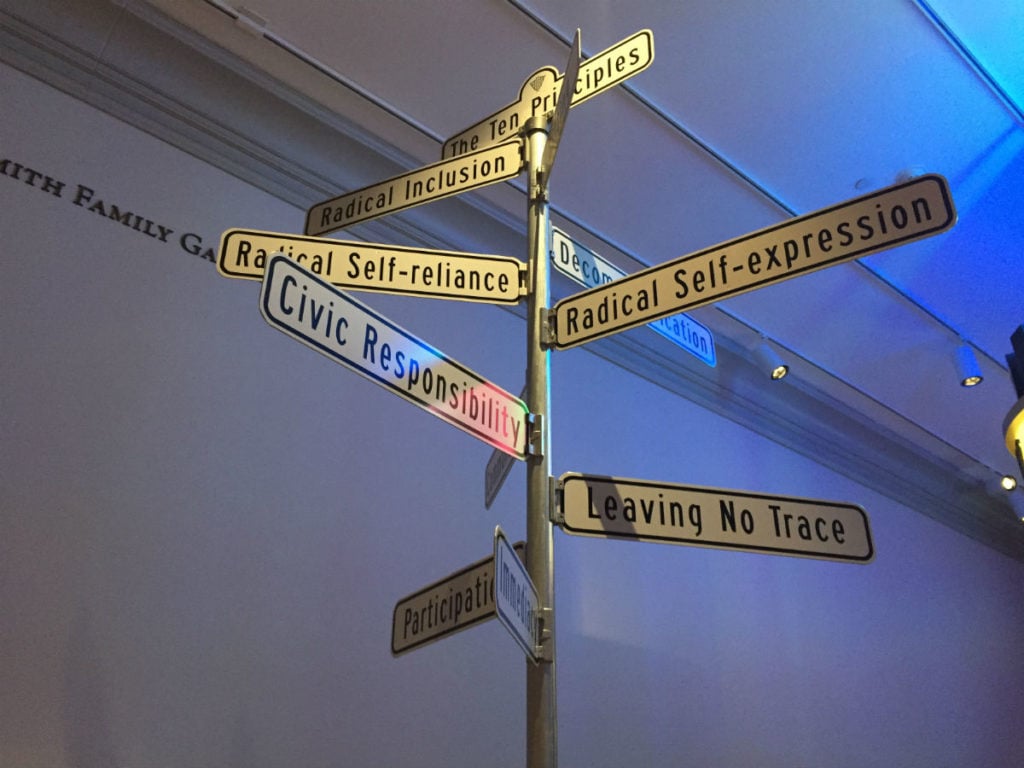

Scott Froschauer, Ten Principles (2017) in “No Spectators.” Image courtesy Ben Davis.

“Immediacy” is the tenth of founder Larry Harvey’s famous 10 Principles for Burning Man—“in many ways,” the FAQ explains, “the most important touchstone of value in our culture.”

The chorus of “Burning Man Hate” has really been gathering force in the 2010s. The truth is that, as the festival has become more of a playground for fashion influencers, celebrities, the jet-setting uber-wealthy, and would-be versions of all three, it has become more self-conscious and scene-y, easier to deride as an “Instagram Party.”

Burning Man participants, 2013. Photo by Neil Girling. Image courtesy Renwick Gallery.

Turning Burning Man art into a museum show is another outgrowth of the same trendiness. It also can’t help but extract the phenomenon from its animating immediacy, asking you to judge and compare the objects in fussy museum-ish ways when their charm is their thundering un-fussiness. Again, what I got from the actual Burning Man experience was that sometimes suspending obsessive critical judgement can have its function.

Look, I know I’m not supposed to say that, as an art critic.

There are many, many powerful aesthetic experiences that are only accessible through drawing ultra-self-conscious distinctions, digging into some odd bit of symbolism or history, finding some precious kernel of meaning.

But then there are other really important kinds of experience that you find with the trash instead of the treasure. Say, at some basement party listening to some friend’s messy band—that feeling of being synced up with the moment and the people around you.

Either half of this equation can get in the way of the other. Society is both over-calculating and anti-intellectual. Personally, I think it is a worthwhile skill to be able to navigate both sides.

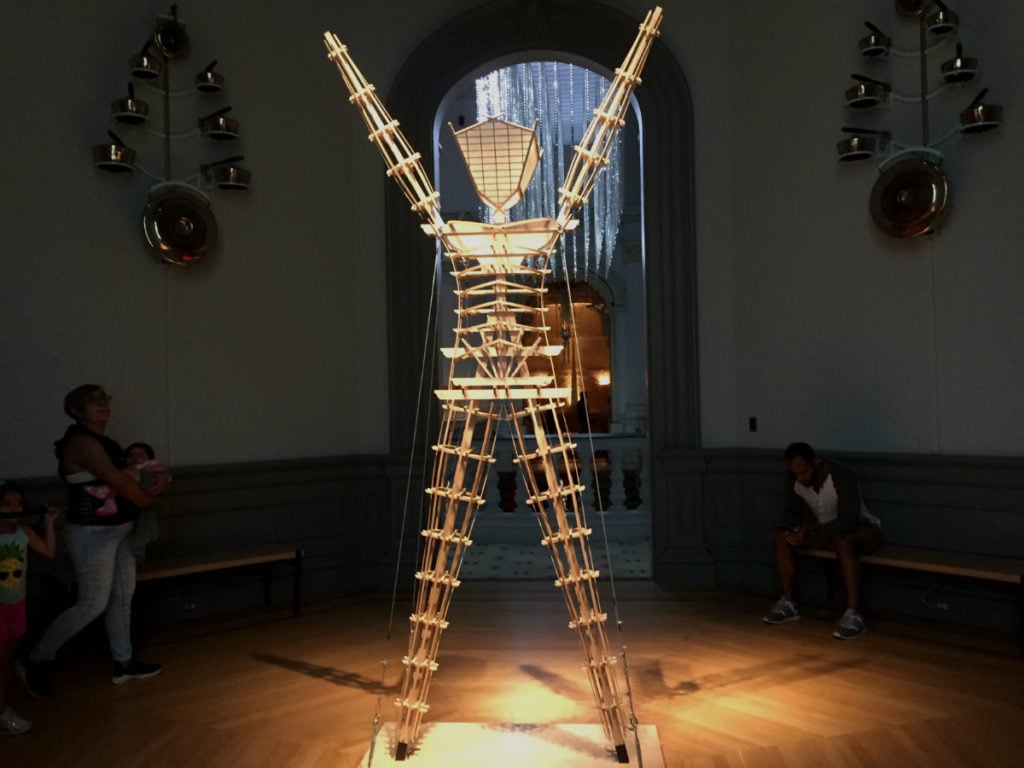

Model of the Man in “No Spectators.” Image courtesy Ben Davis.

It is not disqualifying to say that the Burning Man festival does not tend to generate art for the ages; it would be weird to say it does. It is literally centered around the burning of a sculpture, a monument whose temporary nature is very much a part of what it is.

Devotees will know that the Temple Burn, on the night after the Man Burn, is for many the most redemptive part of the experience. Every year, artist David Best builds an elaborate temple structure, an architectural folly of CNC-routed plywood. There, people leave little notes and photos and tributes to lost loved ones, hoping to receive some catharsis as they watch the structure be consumed by flames.

David Best, Temple (2018). Photo by Ron Blunt. Image courtesy Renwick Gallery.

At the Renwick, in one big gallery, Best has recreated one of his Temples. It’s certainly the most absorbing part of “No Spectators,” where you can sit and contemplate the whole thing and watch others do the same.

Does it work here? You are encouraged to recreate the experience of leaving a personal message, writing on a little piece of wood. As you’d probably expect in this context, there were certainly people using the opportunity to crack wise or make fun of the earnestness of the whole thing.

But there were also definitely people taking the chance to leave sincere notes about their losses and worries in the nooks and alcoves of Best’s “No Spectators” shrine.

The same qualities that make it easy to make fun of here are what also let it play an important psychic function, for some. That sums up the whole phenomenon, in a way.

“No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man” in on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Renwick Gallery, in Washington, DC, through January 21, 2019.