Had she lived, Charlotte Salomon would have turned 100 in 2017. Instead, the German-Jewish artist and her unborn child died at Auschwitz in October 1943. What she left behind, however, was a deeply personal series of nearly 800 gouache paintings, titled “Life? Or Theatre? A Play With Music.” This fall, in honor of the artist’s centenary, the works are being shown in their entirety for the first time, at Amsterdam’s Jewish Historical Museum.

“There’s not a single day that people don’t write to us or call us about Charlotte Salomon,” exhibition curator Mirjam Knotter told artnet News, calling her work the most important part of the institution’s collection. “It’s a massive artwork that it has been impossible to show in one place until now.”

One of the most troubling pieces in her archives, in fact, wasn’t revealed until 2015. In a new edition of Salomon’s complete works, Parisian publisher Le Tripode included a 35-page letter in which she described feeding her grandfather a poisoned omelet and watching him die. Salomon even painted him in death, the resulting work hinting at their troubled relationship.

“The problem is, we don’t know what’s true and what’s not true,” said Knotter, noting that the letter isn’t handwritten, but painted in the same style as the written components of her work. “The whole artwork is a play on fact and fiction.”

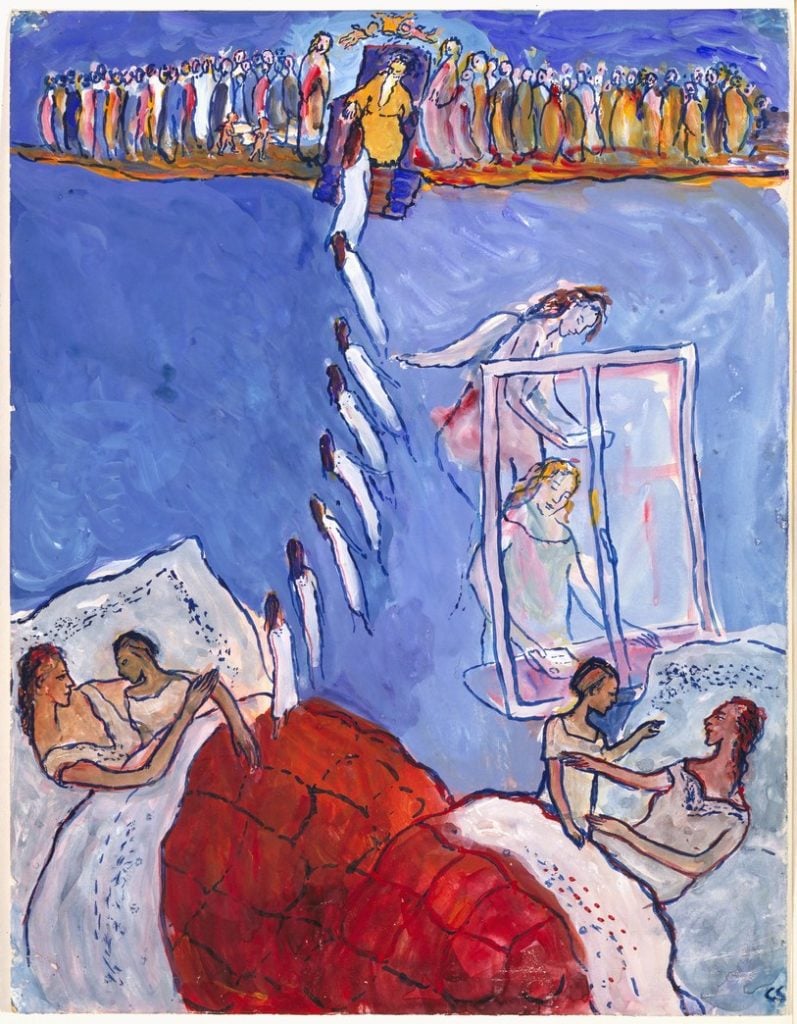

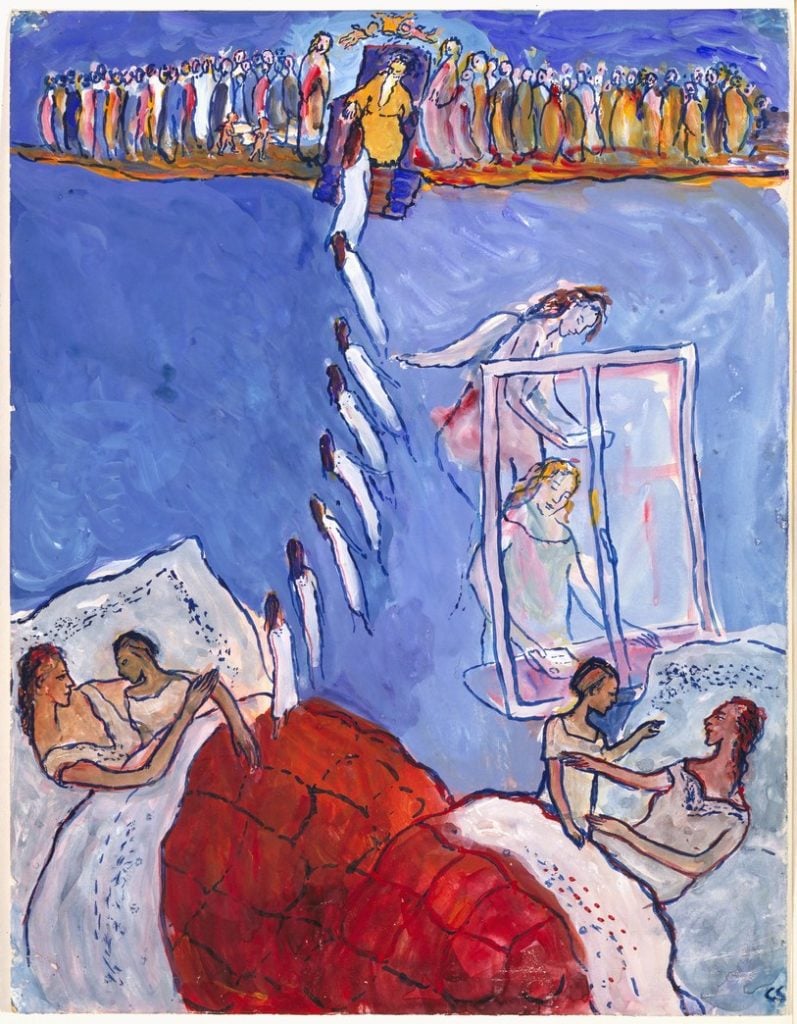

Charlotte Salomon, the young Charlotte waits for the angel of her mother in the “Life? Or Theatre? A Musical Play” series. Courtesy the Jewish Historical Museum © Charlotte Salomon Foundation.

For Salomon, art was a means of warding off her family history of mental illness. She was named after her late aunt, who drowned herself in 1913. Salomon’s mother, Franziska, followed suit in 1926, jumping out the window to her death while recovering from an opium overdose.

In 1938, Salomon fled to the south of France to live with her grandparents. There, her grandma also killed herself, and her grandpa revealed the truth of the family’s dark tendencies toward suicide, previously concealed from Salomon. (Altogether, she learned, seven members of the family had taken their own lives.)

Instead of succumbing to a nervous breakdown, Salomon decided that “I will live for them all,” writing that “I became my mother, my grandmother.” In her art, Salomon tangled with unspeakable tragedy, both personal and societal.

“It was a life-saving project,” said Knotter, a fact that makes the artist’s untimely end at Auschwitz all the more disturbing.

Her grandfather, however, treated her suicide as a foregone conclusion, given the fate of every other woman in the family. “It was impossible for her to live with him,” explained Knotter, adding that if Salomon did, in fact, poison him, “it was the hardest thing she ever did.”

The paintings depict Franziska’s suicide, Salomon’s move from Berlin to France, and what appears to be her first love affair, with German musician Alfred Wolfsohn, who appears in the series 2,997 times. There are also harrowing images of life under the Nazi regime. “It’s not the major topic of the story she wants to tell,” said Knotter, but “when you really look, it’s everywhere.”

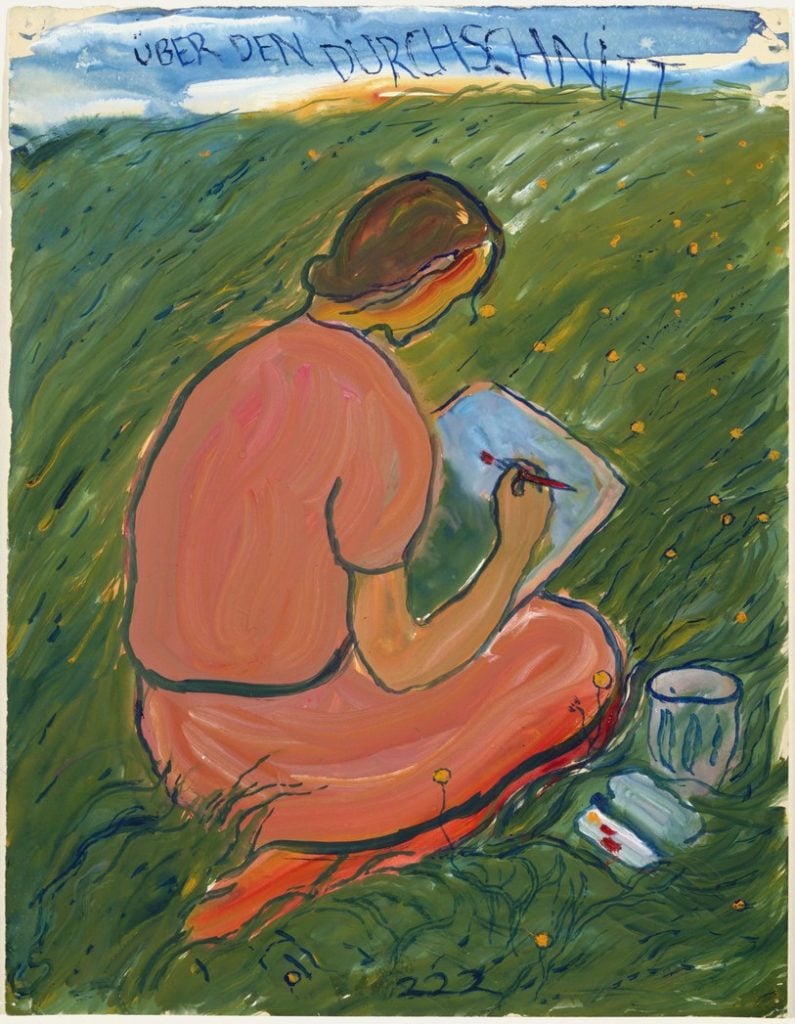

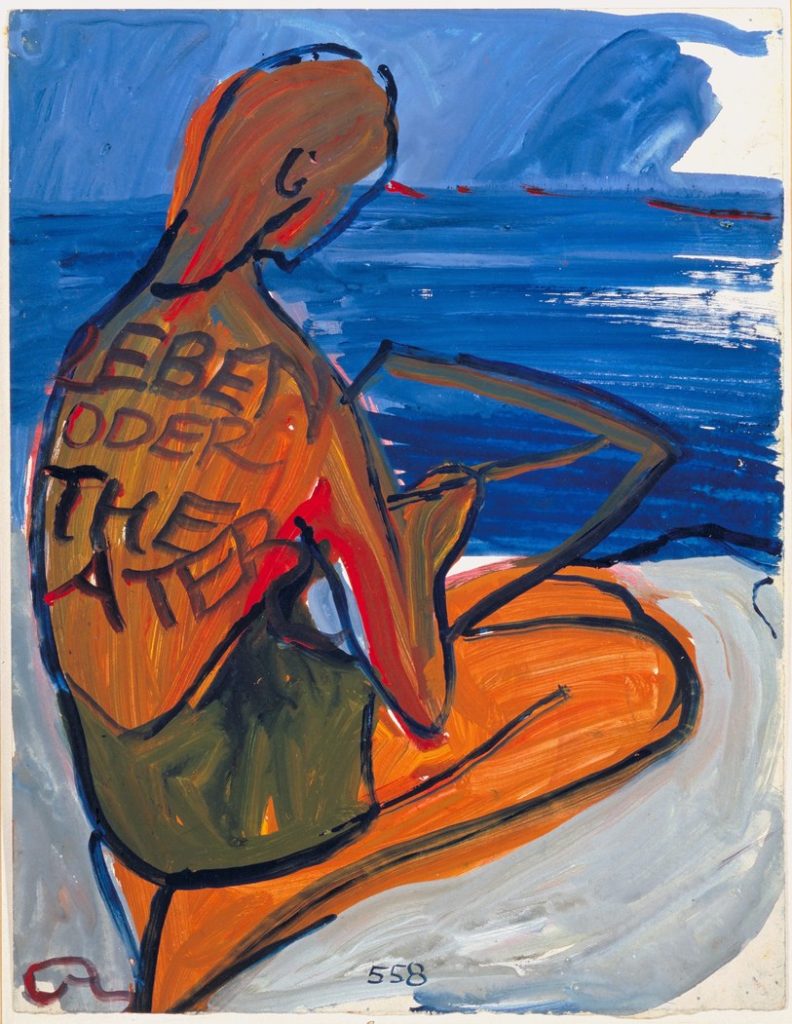

Charlotte Salomon, a self-portrait, the final painting from the “Life? Or Theatre? A Musical Play” series. Courtesy the Jewish Historical Museum © Charlotte Salomon Foundation.

The historical events surrounding Salomon’s work have understandably colored its reception, and it has largely been shown as a sort of Holocaust biography. “In the first years it was shown as a diary in pictures, but it’s not a diary, it’s an artwork,” noted Knopter. “We really want to show what she did as an artist.”

For a time, Salomon had attended Berlin’s Academy of Arts, where she was admitted even amid growing efforts by the Nazis to sideline the Jewish community. As reported by the New Yorker, the admission committee found her so “modest and reserved” that they were convinced she would not “present a danger to the Aryan male students.”

Salomon’s family was a prominent one: Her father, Albert, was the first man to identify breast cancer in an X-ray and is considered the inventor of mammography. He remarried following Franziska’s death, and he and his new wife, concert singer Paula Lindberg, moved in rarefied social circles, with friends like Albert Einstein.

They were also friends with the parents of Anne Frank. It was the young writer’s father, Otto Frank, to whom the couple first showed the vast portfolio of paintings produced by Salomon over her short life. (Previously, Frank had asked for their opinions about his daughter’s now-famous diary.)

Her parents, however, had no idea that Salomon had begun making art again after leaving school, let alone that she had such a monumental artistic output. Before she was rounded up by the Gestapo and killed, Salomon left her life’s work to Ottilie Moore, who owned the villa where the young artist had been living. Moore turned over the brown paper packages of nearly 1,700 works to Salomon’s parents, who had survived the war in hiding, in 1947.

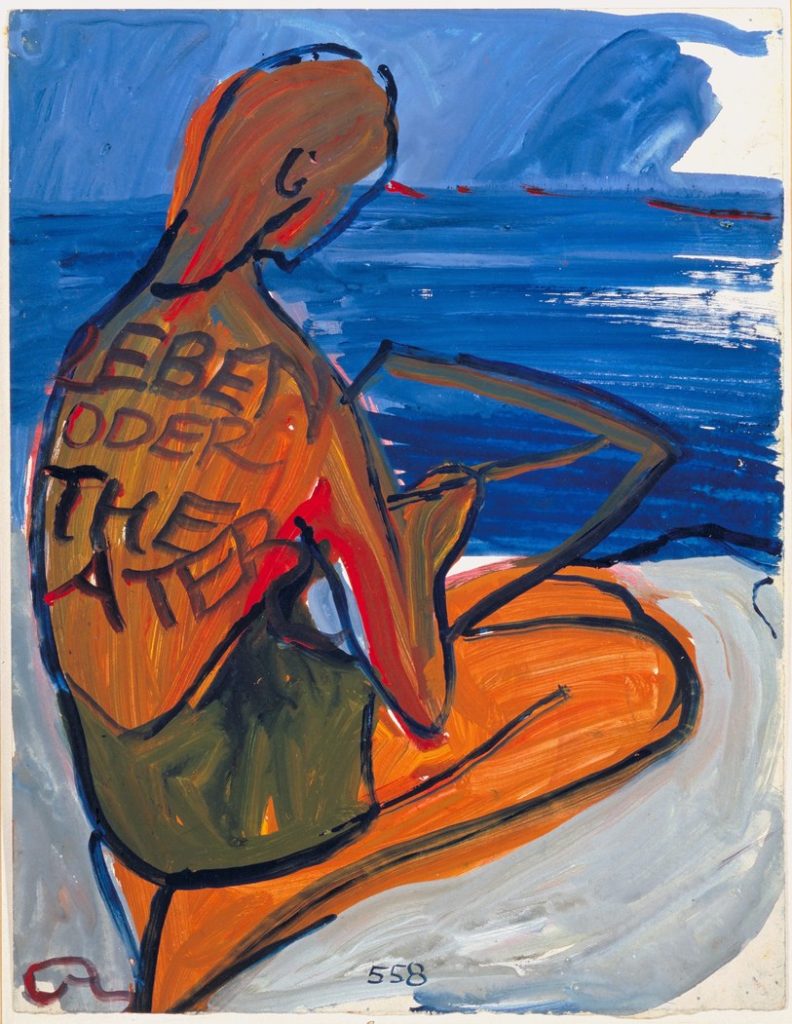

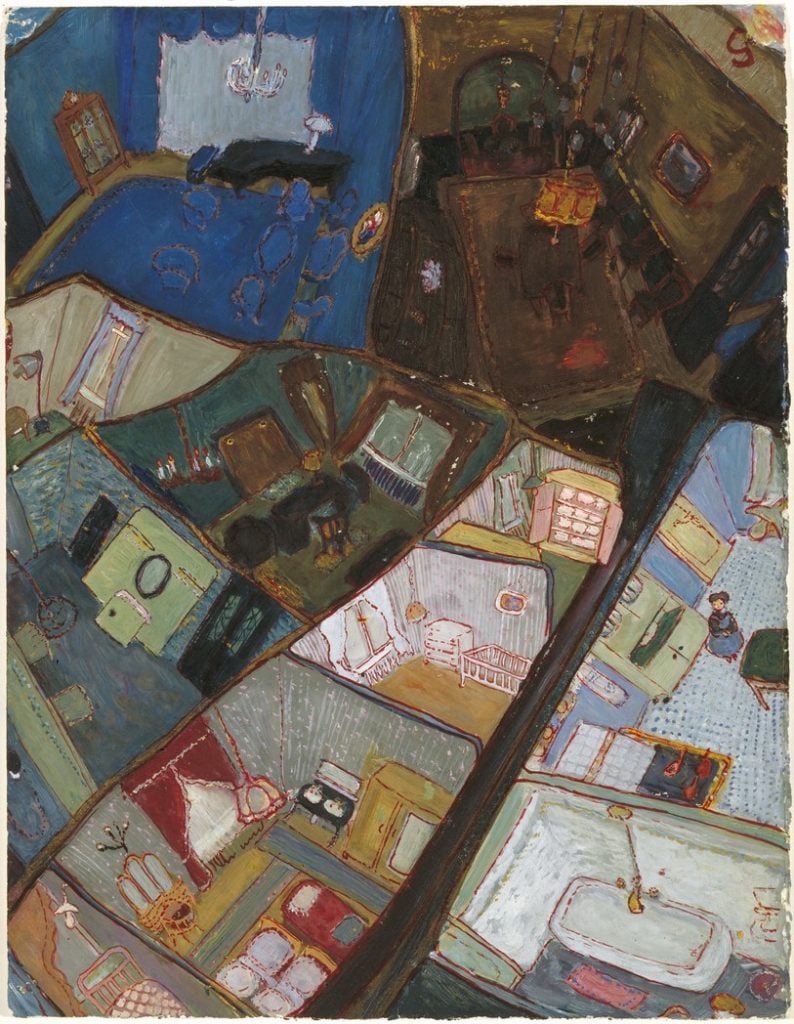

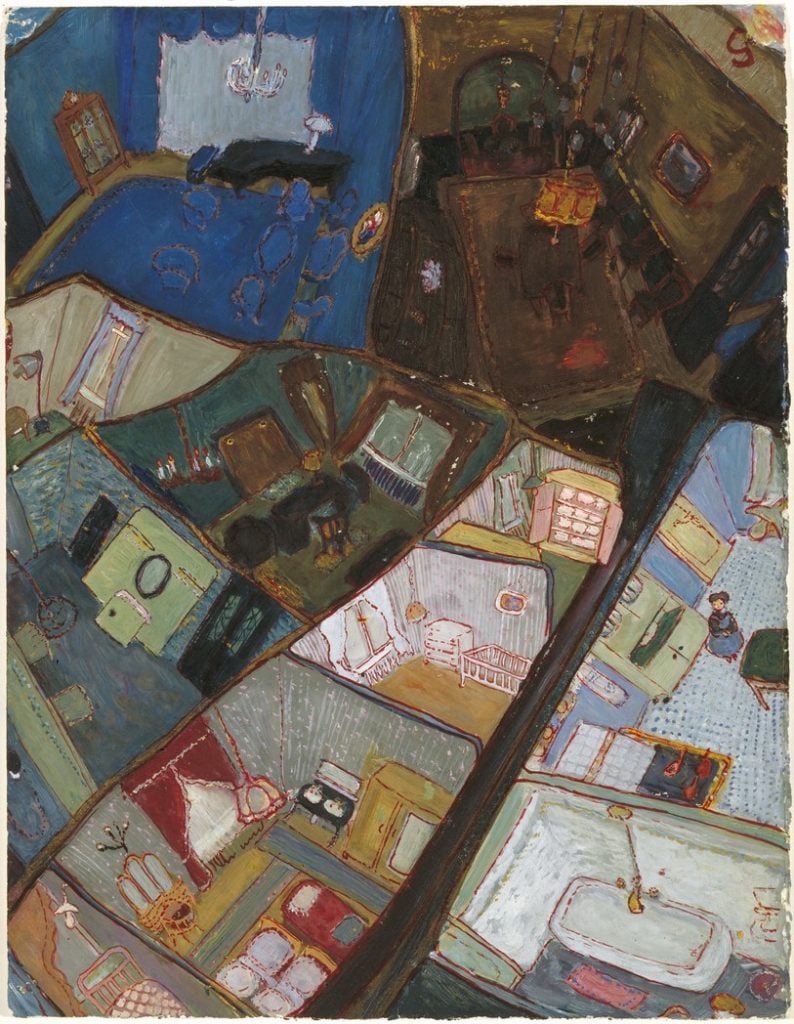

Charlotte Salomon, an early work depicting her family’s apartment. Courtesy the Jewish Historical Museum © Charlotte Salomon Foundation.

What they discovered was a totally unique means of making art, a therapeutic process during which Salomon would sing tunes of her own composition about the subjects of her paintings while she was working on them. The musical notes for these songs were inscribed on the back of her works, which has led some to confuse “Life? Or Theatre?” for an opera. In fact, the notes represent the melody connected to the piece’s inception.

“It’s very important that people know she wasn’t just painting her life,” Knotter explained. “She was singing, she was using her voice.”

Seventy years later, the artist’s most ambitious work is getting its most complete outing, shining a light on this under-recognized figure. “‘Life? Or Theatre?’ is so different in storytelling and form,” said Knotter. “I think it’s one of the major [body of works] one should know.”

“Charlotte Salomon” will be on view at the Jewish Historical Museum (Joods Cultureel Kwartier), Nieuwe Amstelstraat 1, 1011 PL Amsterdam, October 20, 2017–March 25, 2018.