Art & Exhibitions

Christopher Williams at MoMA: The Aesthetics of Smartypants

Prepare to have your mind blown: the photos in the show are hung extra low.

Prepare to have your mind blown: the photos in the show are hung extra low.

Ben Davis

The only thing more frustrating than a Christopher Williams show is someone pretending not to be frustrated by a Christopher Williams show. Because you are. Admit it. He is trying. So. Hard. To frustrate you. Nevertheless, my problem with the Roxana Marcoci-curated “The Production Line of Happiness,” as the current Williams retrospective at MoMA is called, is not that: I like difficult art. It’s that the difficulty Williams purveys feels canned and over-mannered, an academicized version of that caricature of pedantic indie-rock cool, “It’s so obscure, you’d never get it…”

“I’m actually a little puzzled when people say that I’m interested in a lack of transparency or making puzzles,” the 58-year-old Düsseldorf-based American photoconceptualist told New York’s Julie Baumgardner recently. “I think my work is a lot more direct than people allow it to be.” To which I respond: Oh really, Christopher? Let me describe your current MoMA retrospective to you.

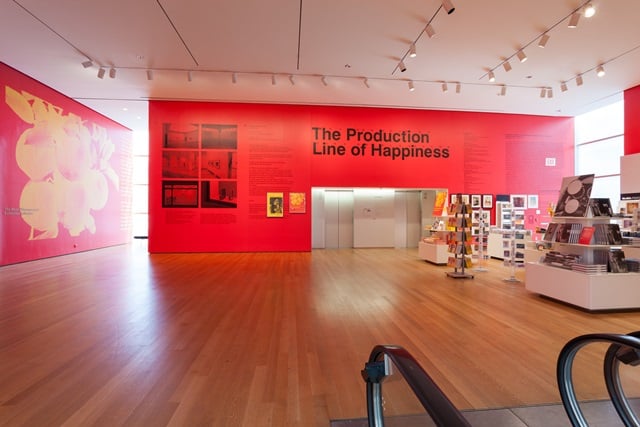

Installation view of “Christopher Williams: The Production Line of Happiness” at The Museum of Modern Art, New York (July 27–November 2, 2014).

Photo by Jonathan Muzikar. © 2014 The Museum of Modern Art

The 60-plus smallish photographic works in “The Production Line of Happiness,” hailing from throughout three-and-a-half decades of Williams’s career, convey a signature interest in difficult-to-read images: a series of unlovely, vacant black-and-white landscapes, seen from different angles; images of unremarkable scenes that are clearly set-up; lots of objects posed against neutral backgrounds, like ads without the copy. It is never clear what exactly the context of the images is, and they are rarely formally beautiful enough to be enjoyed without some idea.

For this show, Williams has insisted that there be no wall text, thereby doubling down on the inscrutability. There is a complex checklist you can pick up, which features only the titles of the works, which are often extremely verbose—sort of like wall texts themselves, though never with enough information to explain anything. One, for a 2000 picture of a car turned on its side, runs more than 200 words, detailing the vehicle’s make and model, its price, specific data on the engine, chassis, and construction, and where the photo was taken, but singularly failing to explain why you should care.

Christopher Williams, Model: 1964 Renault Dauphine-Four, R-1095 / Body Type & Seating: 4-dr-sedan–4 to 5 persons / Engine Type: 14/52 Weight: 1397 lbs. Price: $1,495.00 USD (original) / ENGINE DATA: / Base Four: inline, overhead-valve four-cylinder / Cast iron block and aluminum head. W/removable cylinder sleeves. / Displacement : 51.5 cu. in. (845 oc.) / Bore and Stroke: 2.23 × 3.14 in. (58 × 80 mm) / Compression ratio: 7.25:1 Brake Horsepower: 32 (SAE) at 4200 rpm / Torque: 50 lbs. at 2000 rpm. Three main bearings. Solid valve lifters. / Single downdraft carburetor / CHASSIS DATA: / Wheelbase 89 in. Overall length, 155 in. Height: 57 in. / Width: 60 in. Front thread: 49 in. Rear thread: 48 in. / Standard Tires: 5.50 × 15 TECHNICAL: / Layout: rear engine, rear drive. Transmission: four speed manual / Steering: rack and pinion. Suspension (front): independent coil springs. / Suspension (back): independent with swing axles and coil springs. Brakes: / front/rear disc. Body construction: steel unibody. / PRODUCTION DATA: / Sales 18,432 sold in U.S. in 1964 (all types) / Manufacturer: Régie Nationale des Usines Renault; Billancourt, France / Distributor: Renault Inc., New York, NY., U.S.A. / Serial number: R-10950059799 / Engine Number: Type 670-05 # 191563 / California License Plate number: UOU 087 / Vehicle ID number: 0059799 (For R.R.V.) / Los Angeles, California / January 15, 2000 (No. 6) (2000).

Photo: Courtesy The Art Institute of Chicago, Emilie L. Wild Fund, 2004.21 © Christopher Williams

Williams has also insisted that all the photos at MoMA be hung below normal height, forcing you to stoop slightly (and also, I think, making the light hit the glass wrong, leading to some literal inscrutability amid the glare). Why? He explains, “[Y]ou’re confronting the idea that they should be higher and then the question is why should they be higher?” Of all the burning issues that need to be confronted about museum culture, our tyrannical notions about appropriate hanging heights would not be first on my list. This is about as twee and self-indulgent as institutional critique gets.

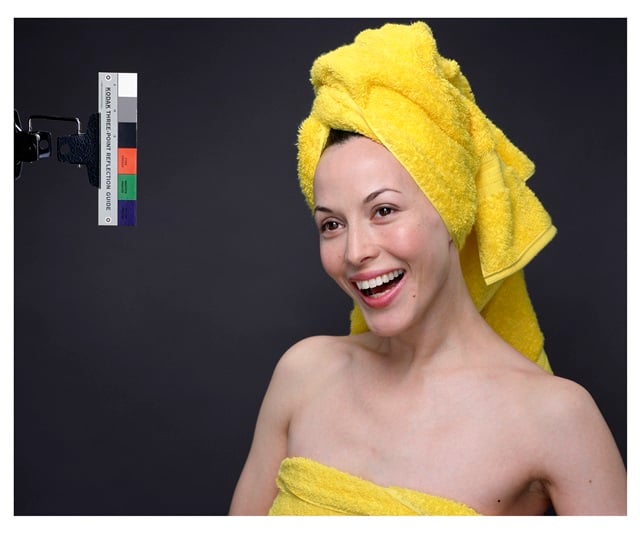

At his best, Williams’s photographic artworks, often made with the help of commercial photography studios, employ a combination of crispness and coyness to conjure an image whose details are so obviously over-specified, but nevertheless so semiotically mute, that it needles at you in a memorable way. This is true, for instance, of a pair of images of a woman identified in a caption as “Mieko.” In one she smiles, in the next she does not. In both, her hair is wrapped in a bright yellow towel. A color control strip of the kind that you find at the margin of photographic prints is included in the image to the left. It’s missing the key color yellow.

Christopher Williams, Kodak Three Point Reflection Guide / © 1968, Eastman Kodak Company, 1968 / (Meiko laughing) / Vancouver, B.C. / April 6, 2005 (2005).

Photo: Courtesy of the artist; David Zwirner, New York/London; and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne © Christopher Williams

All Williams’s images have highly specific back stories about all their many hyper-groomed details—back stories that there is no convenient way to access here. But even if the loyal MoMA believer goes off to seek out Williams’s stories, does it enrich us to discover that the model with the towel was chosen according to the precise dictates of a casting notice by the revered French director Jacques Tati? Not really. But maybe the specificity of what Williams is doing in each case doesn’t matter at all, and the works are conveying the sense of the gap between what you see and what you get. If so, the result combines all the raw drama of stock photography with all the fun of being stuck at a party with that guy who answers every question with another question.

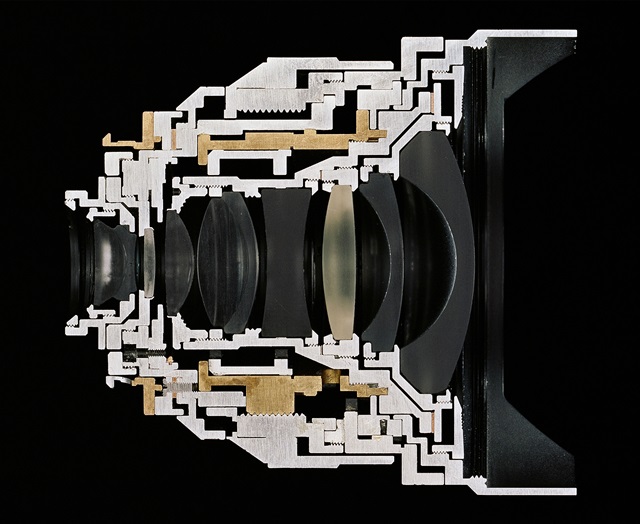

I find something retro about Williams’s obsessions, which seem tethered to the now-passed intellectual moment of 1980s-era photographic, conceptual, and appropriation art with which he is often associated, when the image had an authority it does not now. Williams is very, very invested in assaying the arcana of photo production of the professional, non-digital variety (since this is mainly a retrospective, you can’t fault him for not addressing technology that wasn’t around when he was working; but he compares unfavorably in my mind to the recently passed German filmmaker Harun Farocki, who had similar concerns with highlighting media artifice, but who found new riddles to explore in the digital right up until his last work). Williams often homes in on things taken apart or cut into cross-sections so that you can stare into their guts, in particular high-end cameras, cut cleanly in half so that you can see all the interlocking plates and nested lenses of the apparatus, as if you were looking at the section of a tree, trying to read the secret history of climate coded into its rings. The results can be lovely, in a natural history museum kind of way.

Christopher Williams, Cutaway model Zeiss Distagon T* 2.8/15 ZM / Focal length: 15mm. Aperture range: 2.8 – 22. No. of elements/groups: 11/9 / Focusing range: 0.3 m–infinity. Image ratio at close range: 1:18 / Coverage at close range: 43 cm × 65 cm. Angular field, diag./horiz./vert.: / 110/100/77˚ / Filter: M 72 × 0.75. Weight: 500 g. Length: 86 mm / Product no. black: 30 82016. Serial no.: 15555891. / (Subject to change.) / Manufactured by Carl Zeiss AG, Camera Lens Division, Oberkochen, Germany / Studio Rhein Verlag, Düsseldorf / January 18, 2013 (2013).

Photo: Courtesy private collection © Christopher Williams

But what secret message do you find in this cutaway image of the camera? By foregrounding cameras and their surrounding paraphernalia (like that color bar), Williams’s images function as a reminder of the labor and processes that go into making the image, it’s technical constructed-ness. Even five years ago it might have been different, but it is striking how trite this moral feels in the digital present. Everything is Photoshopped, filtered, meme-ified; most museum-goers, I venture to say, will already know that images are plastic and mutable and rhetorical. HSBC, the big global bank, has an ad campaign that takes the form of the same image, repeated three times, with three different captions: a bald head seen from the back, for instance, labeled variously “STYLE,” “SOLDIER,” and “SURVIVOR.” An arch hipness about media artifice is a basic element of a certain mainstream notion of cool. There has to be something more to the gag, intellectually, than just nagging you, over and over and over and over, with the reminder that things are set-up; since there’s not here, and the payoff of digging in behind the scenes is far from clear, the work seems to have all the wit of “Interrupting Cow.”

Meanwhile, all this pseudo-critique is just a smokescreen for a very specific form of aesthetic pleasure that should be critiqued itself. “I am interested in a descriptive activity that has such a blunt specificity that it transcends its informative function,” Williams told Artforum, suggesting that he is going for a vibe that can only be called meta-pedantry. In his 1957 book Mythologies, Roland Barthes talked about how modern media culture operates sneakily on two levels, offering an obvious, denotative meaning but then also slipping in a second, connotative meaning, the way, say, an image in an ad might show you a car, but also really be about insinuating, “This machine is a chick magnet.” Uncovering such machinations is partly what Williams’s art is about.

But it’s quite obvious that you can turn the same form of criticism back on Williams’s own photos: Whatever unique bit of intellectual trivia he is holding forth on in any particular image, there’s a secondary meaning advertised by every one, telegraphed by the entire elusive/allusive apparatus of the work. The mythology of Christopher Williams’s art can be summed up in a single sentence: “I am just so, so, so smart.”

“Christopher Williams: The Production Line of Happiness” is on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, through November 2, 2014.