Reviews

How Delacroix’s Revolutionary Art Was Forged in the Fires of Counterrevolutionary France

The French Romantic lived through dramatic times, and helped shape their mythology.

The French Romantic lived through dramatic times, and helped shape their mythology.

Ben Davis

“I may not have fought for my country but at least I shall have painted for her.” So said Eugène Delacroix of his most famous painting, Liberty Leading the People (1830).

It’s a ringing statement, much quoted. From the leader of French Romanticism, it gives us the skeleton key to the Romantic myth of the artist: the artist whose formal innovations are forged in the fires of the age, whose creative convictions drive the world forward.

Except Delacroix’s example also shows how that is a bit of a mystification.

The great painter was a revolutionary in art but a moderate in politics. Born in 1798, his father had been a high-ranking Napoleonic official. Delacroix’s politics, to the extent that he had them, were Bonapartist, not republican. He believed in a benevolent dictator; he distrusted the mob. “Hating crowds, he looked upon them as little more than statue-breakers,” wrote Baudelaire, probably his greatest champion.

The outcome of France’s 1830 uprising was pretty much what Delacroix would have considered ideal: Charles X, remembered as one of France’s stupidest kings, was ousted for another king with slightly more popular credentials. The resulting July Monarchy of Louis-Philippe draped itself in the tricolor once more, claiming spiritual closeness to the French Revolution—hence the banner that the bare-breasted, allegorical figure of Liberty waves in Delacroix’s iconic picture.

Detail of Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People (28th July 1830)

(1830). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Still, all allegories are open to many readings, and Liberty Leading the People was a stunningly powerful one—powerful enough that it was kept out of view as potentially a little too inspiring to “the People.” (The master colorist later toned down the red in Liberty’s cap, probably to mute associations with the radical left.)

Liberty Leading the People is not among the paintings that have made the jump across the Atlantic from the Louvre for the Met’s giant new Delacroix show. But that absence may even be for the best if it allows us to look a bit better at the intricacies of how this figure, whose interests have shaped so much of how art is thought about, can be made sense of in the here and now.

A visitor looks at Eugène Delacroix’s self-portrait at the Metropolitan Museum. Image courtesy of Ben Davis.

Delacroix is an outstandingly stylish painter. Even where his subject matter feels remote or stilted, his sheer dynamism—backgrounds are always swirling atmospherically—can carry you pretty far.

If you like painting at all, you probably will find something to like here, from Delacroix’s small portraits of friends and confidants (Léon Riesener, looking like a real heartthrob) to his many and varied canvasses inspired by myth (Medea About to Kill Her Children), literature (Hamlet and Horatio in the Graveyard), and religious themes (Saint Sebastian Tended by the Holy Women) to his frothily accomplished late-career flower paintings.

Eugène Delacroix, Léon Riesener (1835). Image courtesy of Ben Davis.

What you see, beneath all these accomplishments, is appetite—appetite for sensation, appetite for new themes and arenas to prove himself; appetite for success. Unlike colleagues such as Géricault or Vernet, Delacroix had no personal fortune to sustain himself. He was well-born, but his parents both died when he was young, his family status dissolving in the hairpin turns of France’s early 19th century political dramas.

The upshot was that Delacroix had a keen sense of his own destiny, but also the keen sense that he needed to prove himself. That ferocious pride and drive radiates through his output.

A pair of Eugène Delacroix flower paintings. Image courtesy of Ben Davis.

Artists were then not yet in full rebellion against the salon system and the academy. Delacroix made his name with one foot in the world of the official exhibitions, which were associated with the state, and one foot in the private art market, which was expanding rapidly. He cherished the status and respect conveyed by the former, with its hierarchies and proprieties. But he was also keenly influenced by the latter, internalizing the drive to service the market’s hunger for the novel, the edgy, and the titillating.

Eugène Delacroix, Young Tiger Playing With Its Mother (Study of Two Tigers) (1830). Image courtesy of Ben Davis.

Thus you get something like his large painting Young Tiger Playing With Its Mother (Study of Two Tigers) (1830), brimming with feline panache and personality, the lead cat’s head given the imperious dignity that a neo-Classical painter would have given a Roman senator.

Today, it is certain to be among the most lovable works on view at the Met. In France, it was an intriguing puzzle to its observers: Why was this image of an animal (a minor genre) painted at the scope and scale of a history painting (the highest of genres)?

This is the classic Delacroix two-step: the power of the familiar, the shock of the new.

Inspired by English Romantic poet Lord Byron, Delacroix shared the passions of many young Europeans for the cause of the Greek nation, locked in struggle for independence from the Ottoman Empire. His decision to salute it in numerous paintings was one of artistic solidarity—but also simply a calculation that such a subject would be novel, as he put it, “a way to set myself apart.”

In a newly shifting world of artistic entrepreneurialism, topical subjects got attention. Delacroix would know: He had been a model in Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa, a lurid news account in painting form. Succès de scandale was a valid route to fame for a young man in a hurry, which Delacroix definitely was.

Eugène Delacroix, The Death of Sardanapalus (1827). Image courtesy of Ben Davis.

The Death of Sardanapalus (1827), his entry to the salon of 1828, was a little too successful in this regard, widely pilloried as nihilistically shocking. (The giant final version cannot be moved from the Louvre, or even the gallery it is in; at the Met it is represented by two smaller versions.)

It is a fever dream of a painting, depicting a historical tall tale of an Assyrian potentate who, anticipating his defeat, had all his accumulated wealth, including his wives, destroyed. It reaches for that classic-Romantic convergence of anguish and passion, death and sex. The composition is all contorted flesh and cascading treasure.

Sardanapalus himself is draped on the bed at the center, fierce, languid, and sadistically indifferent to the chaos. He is a proxy for both the artist and the spectator, who is given license to luxuriate in the razzmatazz of extremes.

Detail of Eugène Delacroix’s The Death of Sardanapalus. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Now considered a classic, the Death of Sardanapalus also unites the two elements of Delacroix that are ripest for present-day critical scrutiny: his use of women and his Orientalism.

In her classic essay on “The Imaginary Orient,” Linda Nochlin wrote of the Death of Sardanapalus that, though clearly a fantasy of the Exotic East, it was actually less about “Western man’s power over the Near East” than it was about “contemporary Frenchmen’s power over women.”

As that sentence suggests, this “erotic ideology” was hardly confined to Delacroix—though his particular appetites in his studio, via his eloquently confessional personal Journal, became part of the legend of the artist-as-hedonist. Delacroix made meticulous notes to himself of his sittings with his models, marking an X if they had sex, remarking on how much he paid her, and how good the sex was.

Eugène Delacroix, Duke of Orleans Showing His Lover (ca. 1825-26). Image courtesy of Ben Davis.

A work like the Duke of Orleans Showing His Lover (ca. 1825-26), featuring a man raising a sheet to show off the bottom half of a nude woman to her husband—he doesn’t recognize her, that’s the gag—is extra raunchy. It was so, the Met’s wall label says, specifically because Delacroix figured that the racy edge made for good art sales. He can be counted, in this sense, as an innovator in the commercial imagery of sex.

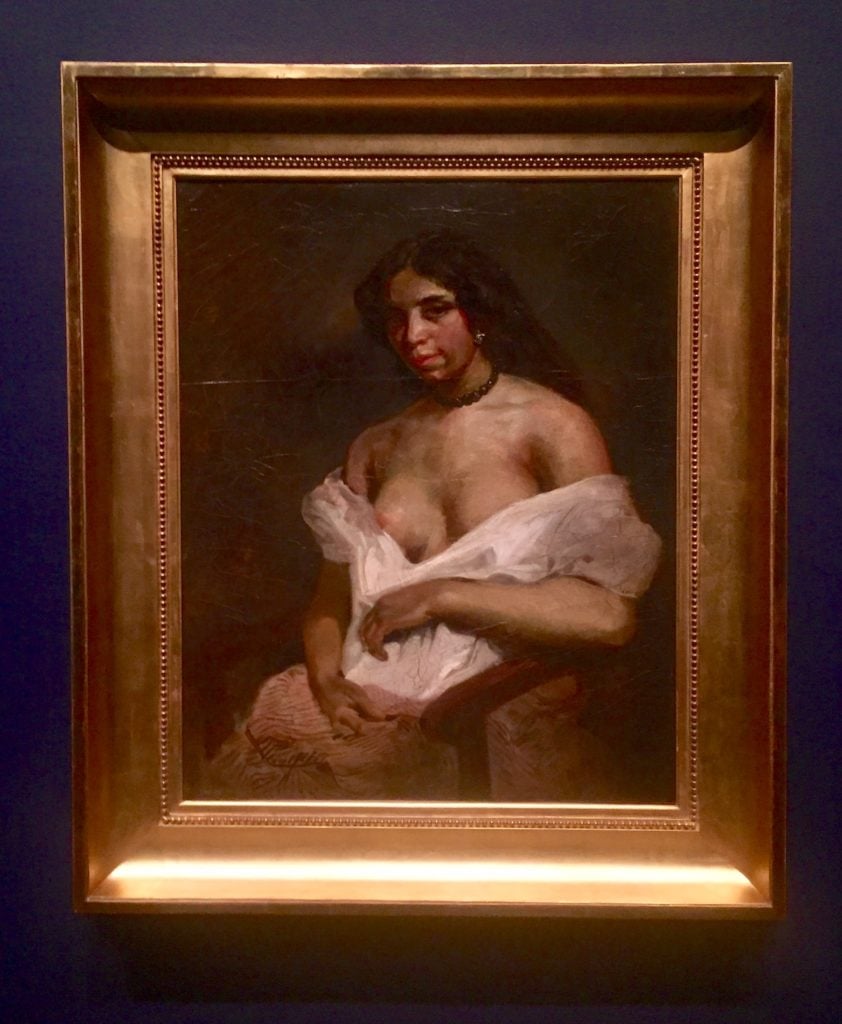

Eugène Delacroix, Portrait of Aspasie (ca. 1824). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

What to make of the enigmatic expression of Portrait of Aspasie (ca. 1824), a very direct, dishabille studio portrait of a multiracial model? Delacroix painted “Aspasie” multiple times. I gather that little biographical information is available about her, or the details of their relationship (Delacroix’s Journal mentions multiple sexual encounters with someone he calls “la nera”—”the black”). Her presence here makes sure that you can’t forget the hierarchies of race, sex, and class that Delacroix’s art participated in and propagandized.

As for Delacroix’s treatment of Orientalist themes, the major period arrived after the critical drubbing he had taken for the fantastical Sardanapalus. His is not quite the consolidated pseudo-scientific picturesque of Gérôme or even the clammy weirdness of his arch-rival Ingres’s later harem scenes. Delacroix would draw motifs that reappeared in his art for years to come from a 1832 trip to North Africa.

It was occasioned by an invitation from Charles de Mornay, France’s ambassador to Morocco. This diplomatic mission to the region was made necessary because France had conquered Algeria in 1830, inaugurating anew its colonial empire. It is worth noting that the same year as Delacroix’s visit, France’s military occupation was on the warpath, driving inland, exterminating the entire Ouffia tribe in the spring. (“May god preserve us from the justice of the French,” one Algerian observer would write.)

Eugène Delacroix, Women of Algiers in Their Apartment (1833–1834). Musée du Louvre, Paris. © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Franck Raux.

The most well-known Delacroix product of this era is Women of Algiers in Their Apartment (1834). This famous painting is actually quite odd, hovering somewhere between a harem fantasy and painted reportage. It is placed deliberately, though subtly, in the present: the woman at center sports a modern timepiece, hung from her bodice. These women seem, in a particular way, unreadable, at this moment when France was still debating what to do with its new imperial holdings.

The show gives Delacroix a lot of credit for calling the space an “apartment” rather than a “harem,” thwarting the conflation of the exotic and the erotic (in evidence in Sardanapalus) that is so characteristic of French Orientalism. Another reading might simply be that the exact balance of realism (used to cloak the exoticism) and fantasy (used to cloak the sordid dynamics of colonialism) had not yet been resolved in these early days.

Eugène Delacroix, Women of Algiers in Their Apartment (1847). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Fifteen years later, when Delacroix returned to the Women of Algiers theme, the pale odalisque on the left has a lower plunging neckline; the black servant figure is now explicitly presented as opening the curtain on a forbidden scene; the window, with its connection to street life and its reality, is gone, as is the detail of the modern watch. The whole thing now recedes into the velvety costumed darkness of a bordello fantasy.

Delacroix, wrote Kenneth Clark, “had the utmost contempt for the age in which he lived, for its crass materialism and complacent belief in progress; and his art is almost entirely an attempt to escape from it into romantic poetry.”

There may be something to this heroic framing—but it is written as if the artist made art only for himself, which Delacroix, ever hungry for recognition, definitely did not. And after all, what is more characteristic of an ultra-materialist society than that it produces this drive towards escapism and puts it to work?

Installation view of “Delacroix” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image courtesy of Ben Davis.

Louis-Philippe’s July Monarchy would eventually crash into the continent-wide revolutionary upsurge of 1848. After the brief detour of the Second Republic (1848-1851), history yielded up another autocracy: Louis-Napoleon’s Second Empire.

This reflux provoked the fury of Karl Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire, which includes some thoughts on the role that artistic mythology played in France’s formative half-century of Revolutionary drama. Thinking of the role that Neo-Classical imagery had played for the leaders of the Revolution of 1789, Marx wrote how the regalia of antiquity provided “the ideals and the art forms, the self-deceptions, that they needed to conceal from themselves the bourgeois-limited content of their struggles and to keep their passion on the high plane of great historic tragedy.”

Having ushered in an expansive industrial capitalism, Marx thought, France no longer needed its cocoon of artistic myth-making: “Entirely absorbed in the production of wealth and in peaceful competitive struggle, it no longer remembered that the ghosts of the Roman period had watched over its cradle.”

And yet… even as Delacroix’s rakish dynamism was specifically forged as a refutation of the pious clarity of Neo-Classicism, upon visiting Morocco and Algeria, he had immediately imagined its real-life inhabitants as living avatars of that longed-for, colorful antiquity. “You’d think yourself in Rome or in Athens, minus the Attic atmosphere,” he marveled.

And so one way to look at Delacroix’s rapaciously inventive, ingratiating art is as furnishing a kind of heroic-Romantic imaginary vocabulary to France’s particular 19th-century hybrid bourgeois-monarchical society. Who better to do so than the man of aristocratic sympathies who also identified as the upwardly mobile, ever-restless striver?

Eugène Delacroix, Lion Hunt (Fragment) (ca. 1855). Image courtesy of Ben Davis.

The “Liberty” of Liberty Leading the People proved to be the liberty of France’s unleashed imperial expansion and laissez-faire speculation under Louis-Philippe. For myself, another example comes from the Second Empire and serves as the finale of the Met show: the giant Lion Hunt (1855). (Its top half, depicting hunters in turbans atop rearing stallions, was lost in a fire in 1870; extracted from its overall plan, the chaos of the lower half, displayed here, looks almost abstract.)

By the mid-1850s, Louis-Napoleon was keen to show off France as the center of capitalist Europe with the Exposition Universelle. Highlighting the nation’s heroic artists as well as its industrial riches was part of the PR scheme. Now in his late 50s, Delacroix’s establishment sympathies and career of innovation put him squarely in favor. He was asked to make an exposition that gathered his greatest hits.

Realism was now the insurgent style in Paris. Delacroix’s Lion Hunt, created to crown his retrospective at the 1855 Exposition, is ultra-vivid in its details—but certainly not at all realist.

Detail of Eugène Delacroix, Lion Hunt (Fragment) (ca. 1855). Image courtesy of Ben Davis.

What you see is a tortured tangle of animal and human bodies, spears and claws, blood and brocade. The giant-sized final canvas is even more crowded than the design in the smaller studies that Delacroix made for it (also on view); the ultimate image drives toward edge-to-edge sensation. It remixes imagery from his hero, Peter-Paul Rubens, with Delacroix’s by then long-established use of the Orient as a cipher for experience at its most intense and sublime. The painting’s savage frenzy is a vehicle for his virtuosity, devoid of any other justifying moral.

Eugène Delacroix, Study for Lion Hunt (1855-56). Image courtesy of Ben Davis.

Lion Hunt gives the formula for pure, mercenary showbiz that we can still recognize today: eye-popping violence, exotic locale, big stunts. If you read it as a career-summarizing manifesto, it is about art as the quest for intense sensation; art as a ferocious struggle for achievement that subordinates all other considerations; dog-eat-dog—or human-vs-lion—competition, enshrined in the glory of larger-than-life artistic metaphor.

“Delacroix” is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through January 6, 2019.