Emojis have officially entered the collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, but those 176 characters probably look a little different than the ones US audiences are used to using to express themselves with. The emoji has come along way since the Japanese company NTT DoCoMo introduced 176 basic 12-by-12 pixel images in 1999.

The brainchild of Shigetaka Kurita, emojis were designed as a way to display images on cell phone and pager screens in a bid to appeal to teenagers. The medium was quickly embraced in Japan. In 2007, when Apple released the iPhone, they knew they needed to incorporate emojis to succeed in the Japanese market.

Curious Americans soon discovered these hidden symbols, originally meant only for Japanese users. In 2011, Apple officially added emoji to American devices, and thus began a great love story for our times, ushering in the global advent of a new, pictorially-enhanced means of communication for the 21st century.

Shigetaka Kurita, NTT DOCOMO. Emoji (original set of 176), 1998–99. Software and digital image files. Gift of NTT DOCOMO Inc., Japan. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

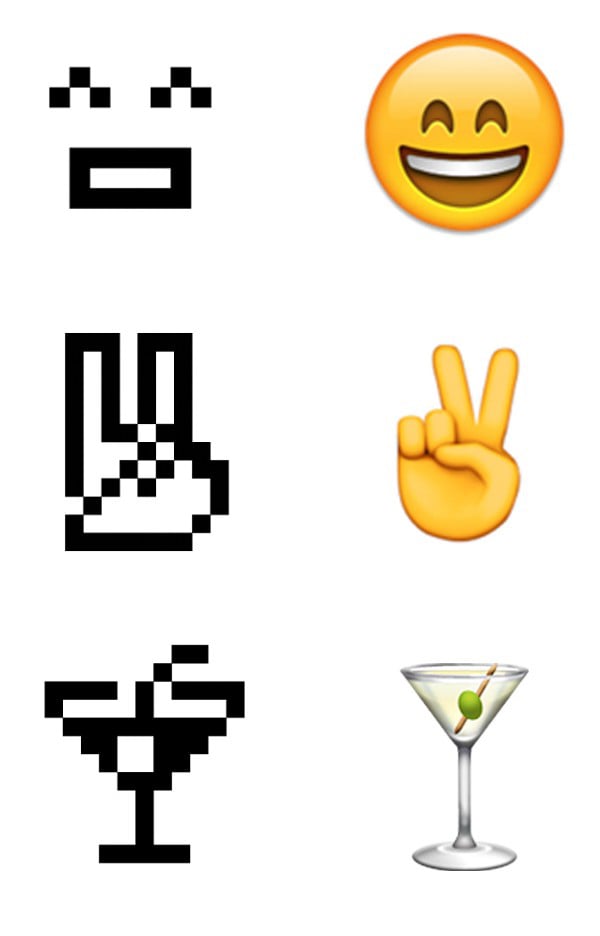

The very first emojis are now somewhat difficult to decipher, but many of the symbols remain universal: the heart, the smiley face, and even the martini glass are easily identified. The digital file for those original emojis is a gift to the museum from NTT DoCoMo.

In its announcement, MoMA called the original emojis “humble masterpieces of design [that] planted the seeds for the explosive growth of a new visual language.”

Today, emojis have truly become a method of communication all their own, with one artist even attempting to translate the Bible into the cheerful graphics. Other projects include emoji celebrity portraits, a version of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Early Delights, and glittery, blinged out sculptures.

1999 NTT DOCOMO emoji compared to 2016 iOS emoji. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

“Emoji tap into a long tradition of expressive visual language,” wrote the museum, noting that the digital objects represent the evolution of ancient hieroglyphics, as well as, more recently, the well-known emoticon, or smiley face, and more complex Japanese kaomojis such as this: ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. “Filling in for body language,” the press release continued, “emoticons, kaomoji, and emoji reassert the human in the deeply impersonal, abstract space of electronic communication.”

The emoji received a multi-ethnic upgrade in 2015. Earlier this year, the Unicode Emoji Subcommittee added 11 new emojis designed to promote gender equality, after complaints that female characters were mostly relegated to dancers and other stereotypical roles. Now, there are male and female versions of all the human emojis.

Today’s iPhones feature 1,851 emoji. To tap into the medium’s history, visit MoMA, where the original set will be on view in the lobby beginning in December.