Reviews

Francis Bacon’s New Major Exhibition Will Transform Our Understanding of His Work

The new catalogue raisonné is also a revelation.

The new catalogue raisonné is also a revelation.

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

Last week, there were two major events relating to Francis Bacon and, on this occasion at least, they didn’t have anything to do with the artist’s record-breaking market, but with a renewed and in-depth understanding of his fascinating oeuvre and artistic process.

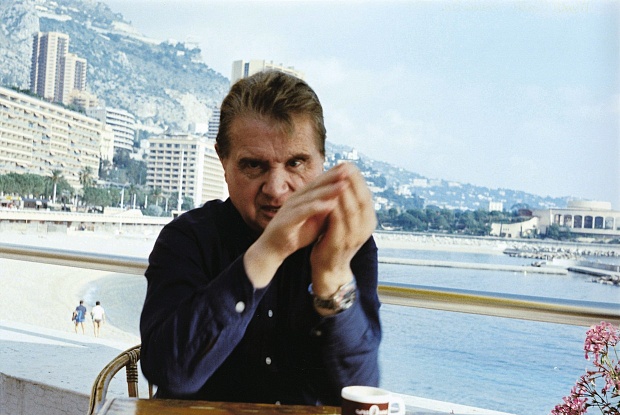

On June 30, the Francis Bacon Estate published a new catalogue raisonné, presenting the 584 surviving paintings that form his complete oeuvre, including many previously unpublished works.

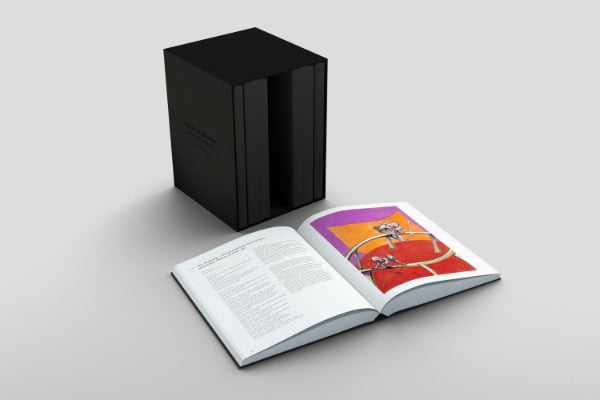

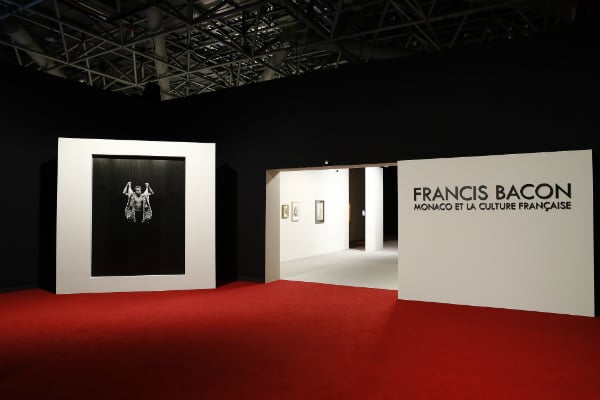

Two days later, on July 2, a major exhibition of his work, entitled “Francis Bacon: Monaco and French Culture” opened to the public at the Grimaldi Forum in Monaco, gathering 66 paintings by the artist alongside works by Modern masters who influenced him, including Pablo Picasso, Alberto Giacometti, Auguste Rodin, Fernand Léger, and Chaim Soutine.

At the core of both the catalogue raisonné and exhibition is Martin Harrison, a Bacon scholar, writer, and curator, who edited the former and curated the latter.

Francis Bacon: Catalogue Raisonné. Edited by Martin Harrison, published by The Estate of Francis Bacon, sold & distributed by HENI Publishing.

The catalog —a stunning five-volume, cloth-bound affair weighing over 15 kilos—is a staggering tour de force a decade in the making, for which Harrison even managed to track down over 100 “missing” paintings that had never been cataloged before.

The handsome publication, with its 538 pages and 800 illustrations, is a collector’s item in itself and, at £1,000 a pop, has suitable collector-worthy price. It even comes foam-crated in a box, like an artwork, so, if it sounds like something you would like to own, be quick, as only 4,000 copies have been released.

The importance of, and need for, this catalog and how it will influence our understanding of Bacon’s oeuvre can’t be overstated, as there’s only one previous edition, the 1964 catalogue raisonné compiled by the then-Tate director John Rothenstein and Tate curator Ronald Alley.

Francis Bacon, Portrait of George Dyer in a Mirror (1968). Fundacíon Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. Photo Hugo Maertens ©The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS 2015.

However, this early catalog only included around 63 percent of Bacon’s total oeuvre—which makes sense, considering he would still live and paint for another 28 years, until his death in 1992 in Madrid. The book, which reproduced the majority of the paintings in black and white, was notoriously difficult to complete.

“[Rothenstein and Alley] had the singular difficulty of having Bacon alive, I didn’t suffer from that,” Harrison said in November last year, as his mammoth project was nearing completion.

He did however face a fresh set of challenges, the biggest of which was locating those 100 extant paintings that were scattered all over the world in (very) private hands and had never been cataloged or published publicly before, Harrison told artnet News in over dinner Monaco, the night before the preview of the show.

Installation shot of “Francis Bacon: Monaco and French Culture” at the Grimaldi Forum, Monaco. Photo ©JC Vinaj/Grimaldi Forum.

The expert was in Monaco adding the finishing touches to the installation of “Francis Bacon: Monaco and French Culture,” and displaying the same hands-on approach and attention to detail evidenced in the catalog, as he dealt with the technicians to ensure maximum perfection every single aspect of the exhibition, including the dramatic the lighting.

The exhibition is an absolute triumph. Harrison has put his knowledge of all things Bacon—surely bettered after a decade of research for the catalog—and created a stunning non-chronological journey through Bacon’s oeuvre, bringing to the fore his references and inspiration—some of them more predictable (Picasso and Rodin), and others, for the majority of viewers, less so (who knew Bacon was so moved by Vincent van Gogh’s work that he even painted a series of portraits of the Dutch artist in his signature style in 1956-57?).

Installation shot of “Francis Bacon: Monaco and French Culture” at the Grimaldi Forum, Monaco. Photo ©JC Vinaj/Grimaldi Forum.

Organized in thematic areas (including Inspirations, The Human Body, France and Monaco, and The Triumph of the Grand Palais), the show presents a novel, less clichéd reading of Bacon, with a large number of lesser known and late works in very vivid colors on display.

Among the most beguiling surprises is the 1989 Study for Portrait of John Edwards, whose bright pink background, almost fuchsia, might seem incongruous with Bacon’s palette at first, but once seen makes perfect sense.

Installation shot of “Francis Bacon: Monaco and French Culture” at the Grimaldi Forum, Monaco. Photo ©JC Vinaj/Grimaldi Forum.

Yet, one of the most surprising revelations of the show is not so much to do with technique but with biography, namely, the strong and enriching relationship that Bacon sustained with French culture and France, particularly with the cities of Monaco and Paris, and how it influenced his work.

Surely, what comes to mind when thinking of Bacon’s psycho-geography are the louche streets of Soho in London, and its infamous watering holes, the French House and the Colony Room, as well as the slightly less gritty South Kensington area where he lived. And yet, he spent three years of his life—between 1946 and 49—in Monaco, a city that he would continue to visit for the rest of life, and where the only Francis Bacon Foundation in the world has been established, spearheaded by the Lebanese-born Swiss property developer Majid Boustany (who’s also directly involved in the exhibition).

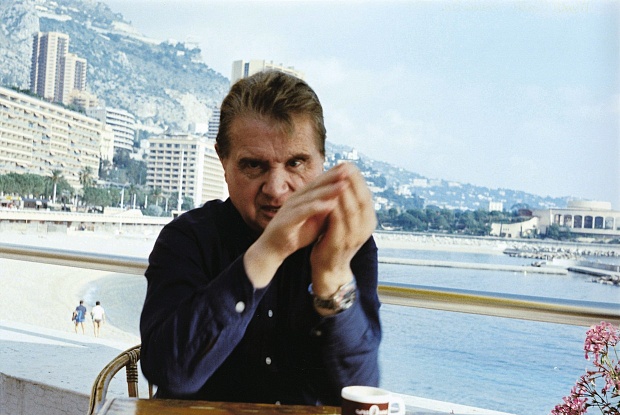

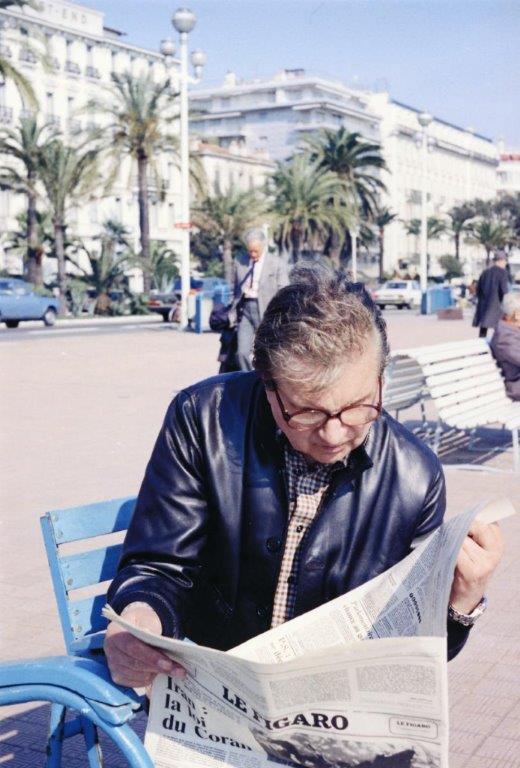

Francis Bacon in Nice in March 1979. Photo ©Eddy Batache.

Admittedly, Bacon’s reasons to settle temporarily in the affluent mini city-state on the Côte d’Azur had quite a lot to do with his less sunny passion for gambling, with the Casino of Monte Carlo being a big draw for deep-pocketed gamblers from across the world. But it wasn’t all drinks and games of dice and roulette on the French Riviera, as his painting also underwent a major transformation during his stay.

Firstly, he began concentrating on the human form, a subject he would explore for the rest of his life. Secondly, it was in Monaco where he began working with the motif of the “Screaming Pope,” his unique take on Diego Velázquez’s 1650 Portrait of Pope Innocent X that would become the subject of one his most recognizable and potent series.

The show is superb—definitely worth a trip if you happen to be in the area during the summer—oozing a sense of gravitas bolstered by the dramatic exhibition design also by Harrison, inspired the Swiss architect and stage lighting theorist Adolphe Appia.

Tall, heavy curtains highlight the vast vertical scale of the space, purple light projected from below creates intriguing nooks worthy of a David Lynch film, and metallic bars in the shape of beams and doors replicate the domestic cages Bacon was so fond of painting to frame his crouching figures—an imprint, no doubt, of the stint, during his 20s, that Bacon spent working as an interior designer.

Installation shot of “Francis Bacon: Monaco and French Culture” at the Grimaldi Forum, Monaco. Photo ©JC Vinaj/Grimaldi Forum.

Towards the end of the exhibition, a vast room homes Bacon’s monumental 1970 triptych Studies of the Human Body, which he painted specifically for his historical 1971 retrospective at Paris’s Grand Palais. The stunning work, which was inspired by Picasso’s distorted explorations of the female form, is suspended mid-air, hovering on top of three curved steps, as if daring the viewer to climb up and grab it. This major work, moreover, is in private hands, so seeing it in the flesh is a genuine privilege.

Nearby, Picasso’s Femme couchée à la mèche blonde (1932), this one belonging to the Nahmad Collection in Monaco, serves as reminder of the Picasso that Bacon loved and fought, the towering figure who was both a role model and a competitor for the British artist.

There’s much to read between the lines in this show, and another of Harrison’s deft touches is the restrained use of interpretive material. It would have been easy for this Bacon scholar to overwhelm those less familiar with the artist and his work with an avalanche of information and minutiae. Instead, we are given a broad narrative to guide us, but are left to fill in the gaps by observing the brushstrokes and visceral shapes up close.

‘Francis Bacon: Catalogue Raisonné’ (ed. Martin Harrison) was published on June 30, 2016 by the Estate of Francis Bacon, priced at £1,000 | $1,500 | €1,400.

“Francis Bacon: Monaco and French Culture” is on view at the Grimaldi Forum, Monaco, from July 2-September 4, 2016. A catalog, edited by Martin Harrison, has also been published to accompany the exhibition.