Art & Exhibitions

Maria Lassnig Paired with Francis Bacon for an Emotional Double Header in Liverpool

Is the pairing doing Lassnig a disservice?

Is the pairing doing Lassnig a disservice?

Hettie Judah

In her 1971 animation Selfportrait Maria Lassnig draws her own face being inked by the rubber stamp of a bureaucrat or archivist: an authoritative bestowal of identity. Lassnig’s rubber-stamping consists of two words: the first “woman,” the second “weak.” Though they may represent how she felt she was seen by the outside world, Lassnig selected these labels herself, so one wonders at her choice of “weak.” Did she see it simply as a corollary of “woman”? Or was it a reference to her commitment to portraying the intimate inner sensations of her body through her art—her Körperbilder (body awareness paintings)? Is the business of emotion and personal feeling “weak”?

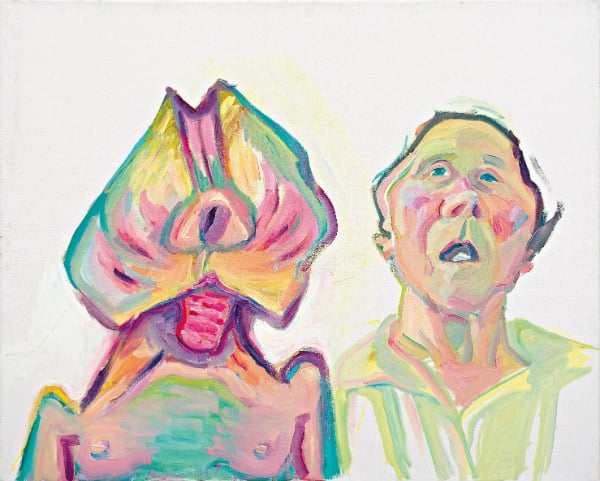

As is evident from a new retrospective of her work at Tate Liverpool, Lassnig was not weak of will. In 1940, in her early twenties she left her respectable job as a primary school teacher in rural Austria to study at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Here, too, she was defiant of expectations. The earliest work in this show, Selbstporträt expressiv (Expressive Self Portrait) from 1945, the year she graduated, shows Lassnig taking a spirited experimental approach to the depiction of self, quite removed from the approved art of the era.

Maria Lassnig, Expressive Self-portrait (1945). Courtesy

©Maria Lassnig Foundation

Lassnig’s less compelling work emerged at those moments where she experienced self-doubt relating to wider tendencies within the art world. Three trips to Paris in the early 1950s, during which she encountered Surrealism and works by the Abstract Expressionists, precipitated a series of cubist-inspired paintings. Their muddy khaki-inflected coloring and the scale-like planes of paint created by the palette knife build a sense of camouflage or concealment quite counter to her deeply seated desire to expose, delve, and explore the self.

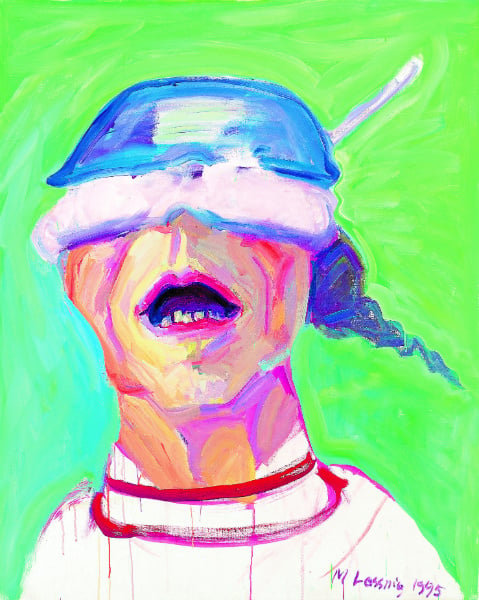

Following a series of expressive Strichbilder (line paintings) on large white-painted canvasses in the early 1960s, Lassnig commenced on her Körperbilder. Populated by anthropomorphic machine shapes and hybridized bodies, these were rendered in flesh tones ranging from the drained to the livid, against a background of antiseptic greens and blues, a palette that would dominate Lassnig’s painted work through to her death, in 2014, at the age of 94.

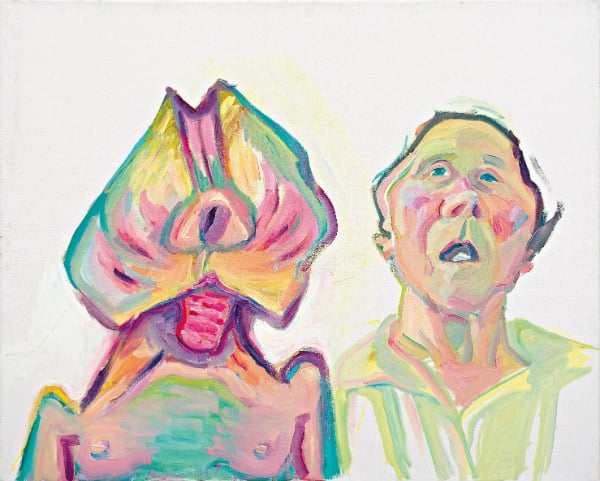

Maria Lassnig, Self-Portrait with Camera, (1974). Courtesy ©Maria Lassnig Foundation ©Artothek of the Republic of Austria, permanent loan, Belvedere Vienna

Tate Liverpool bolts this first UK retrospective of Lassnig’s work onto an exhibition examining Francis Bacon’s use of cages, frames, ellipses and other spatial structures in his paintings. There is some logic to the pairing—both artists were strongly affected by World War II, both explored the human figure in an era of machines, against the rise of photography, both portrayed flesh as in some way plastic, prone to ooze, spread, and distort, unconfined by the limits of the human form. Both, too, produced art that was expressive, emotional, and deeply knotted up in personal experience.

In other ways the pairing does Lassnig a disservice. The two exhibitions are physically twinned, so you must walk through the Lassnig show to get to the Bacon, rather like a supermarket herding shoppers through the “improving” fruit n’ veg department before they can get to the meat and booze they came for.

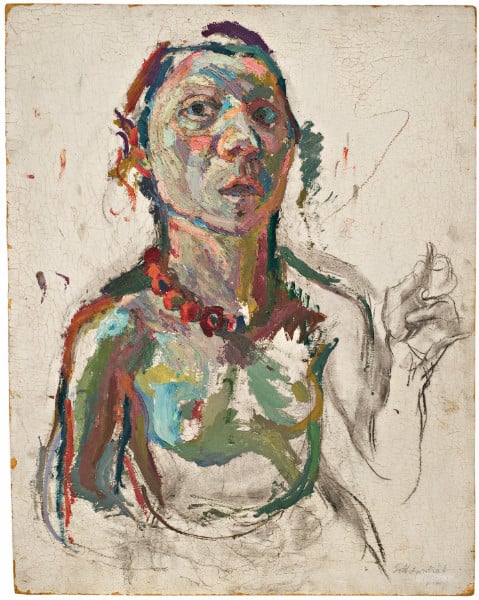

Maria Lassnig, Self-portrait with Saucepan (1995). Courtesy ©Maria Lassnig Foundation

For even the most diligent student of the Lassnig show, it’s hard not to emerge from this sequence of exhibitions feeling so pummelled by Bacon that memories of the show that came before him are recalled through a cloud as if one were reeling from a punch to the head. Where Lassnig explores physical sensation, emotion, and mankind’s relationship to technology with quizzical humor and expressive oddness, Bacon leaps headlong into the abyss. You can’t beat Bacon at pain. Where his mouths are all screaming teeth or bruised with compression as if the face wanted to consume itself, Lassnig’s self portraits often show the artist with her mouth half open as if startled, or perhaps hesitating on the edge of speech.

Yet pain and anger too are part of Lassnig’s artistic vocabulary: a series of paintings created during the first Gulf War show furious blind humanoid figures carried on weapon-like limbs. Toward the end of her life her paintings explored personal sensations of disease and exhaustion—an untitled work from 2005 presents a seeping, near-horizontal form propped up on crutches like an ancient Japanese pine tree. The faces of the convalescents in Krankenhaus (Hospital, 2005) are cartoonish grotesques of pain and exhaustion, but the bodies glimpsed beneath the sheets are warped and abstracted with suffering.

Francis Bacon, Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne Standing in a Street in Soho (1967). Courtesy © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2016. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. Acquired by the state of Berlin

With only ten years difference in age (Bacon was born 1909, Lassnig in 1919) the fact that Lassnig is receiving a tentative introductory retrospective while Bacon is afforded an academically rigorous thematic investigation is also eloquent of their relative positions in the artworld. Lassnig was an innovator, with an individual vision, rather than a copyist of styles established by men that had come before, but of course she was also, as she never allows us to forget, a rubber stamped “woman,” exploring a woman’s sensations and physical experiences.

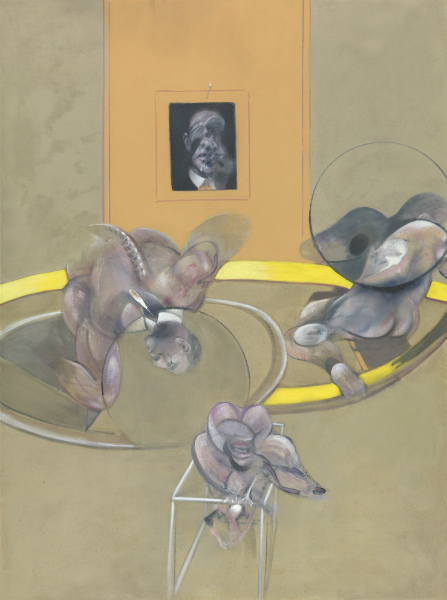

These quibbles are perhaps only to serve as a caveat in approaching two rich and rewarding exhibitions (part of that caveat being precisely that they should be taken as two shows rather than one). Bacon’s use of framing devices in his paintings achieves the twin horror of claustrophobia (the boxed-in subject) and agoraphobia (the threat of the poison-tinted void beyond). Lassnig, even in painting herself emerging from or wrestling with the canvas, feels present and engaged in the space of the gallery. With Lassnig we journey through a shared navigation of life’s difficulties: with Bacon, a private hell.

Francis Bacon, Three Figures and Portrait (1975). ©The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2016. Image courtesy Tate.

“Maria Lassnig and Francis Bacon: Invisible Rooms” are on view at Tate Liverpool until September 18.

“Francis Bacon: Invisible Rooms” will tour to Staatsgalerie Stuttgart from October 7, 2016 – January 8, 2017.