Reviews

‘Gay Gotham’ Reveals Splintered History of New York’s Queer Communities

Solidarity and separation play out in the Museum of the City of New York's new survey.

Solidarity and separation play out in the Museum of the City of New York's new survey.

Rain Embuscado

“Gay Gotham,” the Museum of the City of New York‘s new show opening Friday, October 7, surveys the “queer networks” that thrived throughout the 20th century by tracking the lives of ten artists. Backed by its occasional history lessons, the exhibition delivers on its promise; yet a closer reading reveals a fiercely splintered history marked by individual commitments and glaring reminders that even the queer community isn’t exempt from issues of race, class, and gender.

The show opens with the first half of the century in the second floor gallery, featuring works and personal documents by Harlem Renaissance artist Richard Bruce Nugent; Hollywood-entrenched playwright Mercedes de Acosta; modernist impresario Lincoln Kirstein; New York intelligentsia photographer George Platt Lynes, and the beleaguered composer Leonard Bernstein. Though informative, it’s hard not to read this selection of artists as arbitrary representatives of their moments.

Under the Visible Subcultures sub-section, for instance, a text highlights Mabel Dodge and her come-one-come-all home salon of “bohemianism, radicalism, and sexual freedom.” Nearby, another text on the Harlem Renaissance describes Carl Van Vechten as a “publicity ambassador” for inviting fellow white New Yorkers to participate in the uptown community. Regrettably, both sections read as footnotes to the exhibition.

Andy Warhol and Candy Darling, photographed by Cecil Beaton. Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

Upstairs, Andy Warhol and Robert Mapplethorpe claim walls of their own, replete with photographs, art works, and personal memorabilia loaned by their respective foundations. Dancer Bill T Jones and artist Harmony Hammond share another wall, while photographer Greer Lankton occupies a corner with a signature window display.

At a press preview on Thursday, co-curator Stephen Vider turned our attention to a flier Hammond designed for “A Lesbian Show,” a group exhibition she curated in 1979. “There was already little to no space for women in high art,” Vider explained. “There had never been anything like it.”

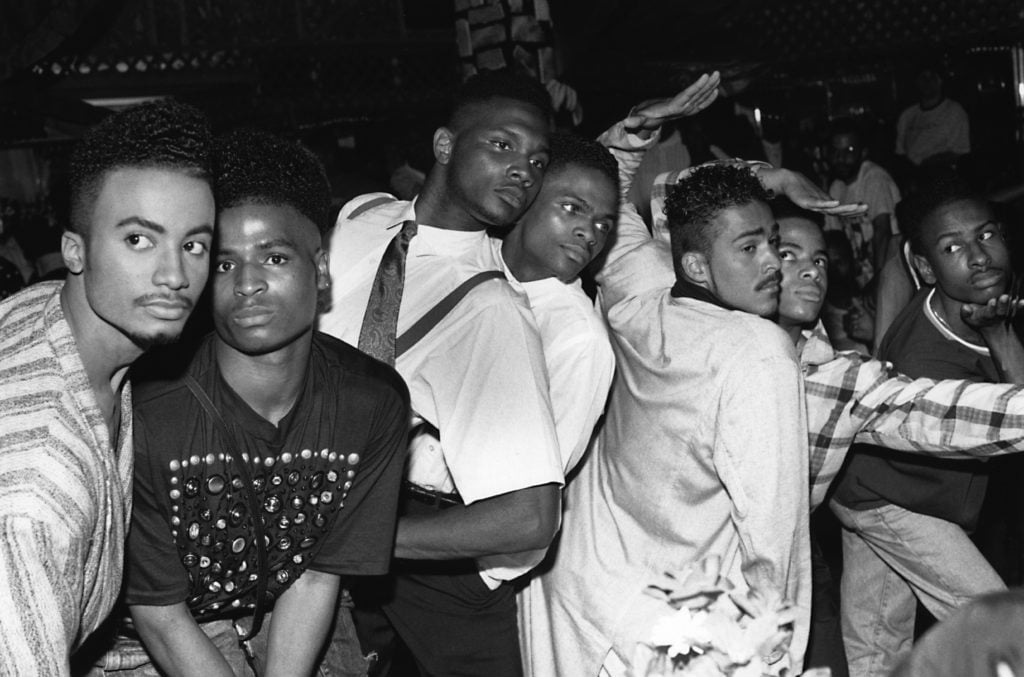

Chantal Regnault, From Left: Whitney Elite, Ira Ebony, Stewart and Chris LaBeija, Ian and Jamal Adonis, Ronald Revlon, House of Jourdan Ball, New Jersey (1989). Courtesy Museum of the City of New York.

Across the room and adjacent to Lankton’s installation is the themed Posing section, which yields an electrifying mix of images featuring turn-of-the-century subcultures: Tseng Kwong Chi’s East Village art scene, Alice O’Malley’s alternative clubs, and Chantal Regnault’s vogue balls. “A lot of gay and lesbian bars in the ’80s and ’90s were engaged in racist practices like double and triple carding,” Vider said.

Taken as a whole, the show successfully frames a century’s worth of history by extolling art as a preservative force for queer artists. “New York has always attracted outsiders who are willing to fight and make space for themselves,” Vider said. But beyond the unifying rubric of sexual variance, “Gay Gotham” underscores, albeit inadvertently, the disappointing reality that the LGBTQ’s constituent communities rarely overlapped.

“Gay Gotham” is an exhibition at the Museum of the City of New York that runs from October 7 through February 26, 2017.