On View

A New Exhibition of Work by Prisoners Defies the Stereotypes of Prison Art—See Highlights Here

An exhibition at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum brings together work by 34 incarcerated artists created over the past 30 years.

An exhibition at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum brings together work by 34 incarcerated artists created over the past 30 years.

Melkorka Licea

From the outside, Connecticut’s prisons look like any other dreary correctional facility in America. But inside, inmates are transforming their jail cells into art studios with the help of the Community Partners in Action (CPA) Prison Arts Program.

Now, Connecticut’s Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum is presenting work by 34 presently and formerly incarcerated artists created over the past 30 years in a new exhibition titled “How Art Changed the Prison: The Work of CPA’s Prison Arts Program,” on view through May 2019.

“This is an exhibition of work by real people trying to do great and good things in dark worlds behind razor wire in your neighborhood,” the CPA’s Prison Arts Program manager Jeffrey Greene, who organized the exhibition, writes in the show’s catalogue. “Please do not see this exhibition as a trip to the zoo or the opening of a cabinet of curiosities. This is an exhibition of sincere attempts to confront darkness.”

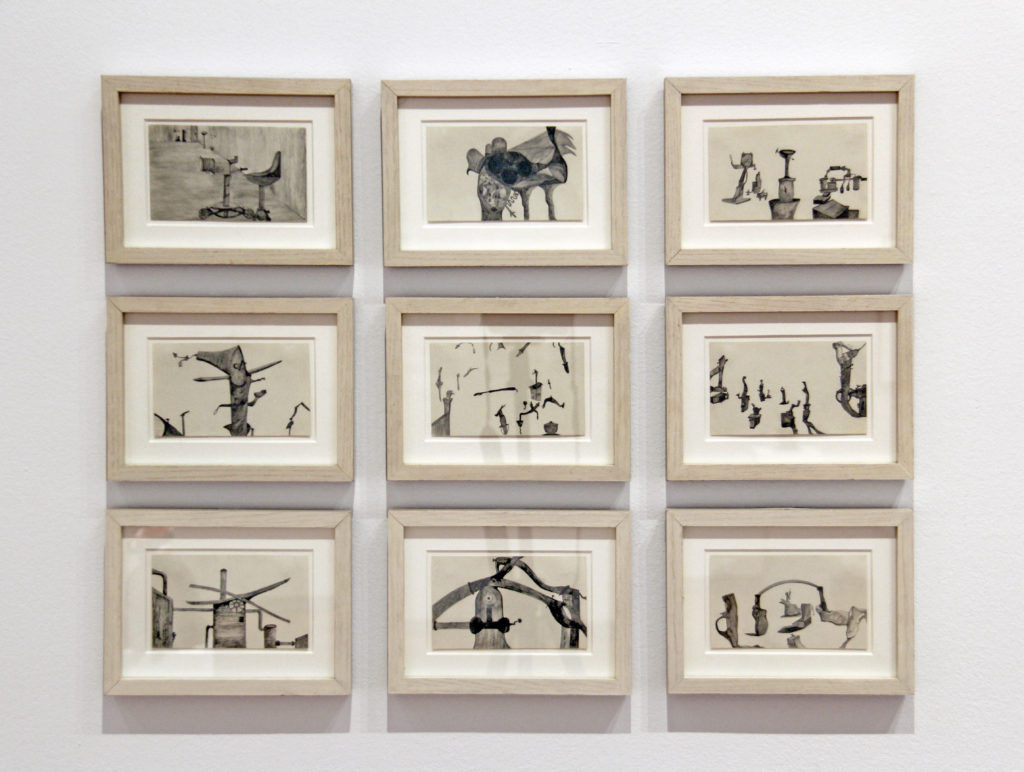

Installation view of “How Art Changed the Prison.” Photo: Christopher E. Manning, courtesy of the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.

The works in the show—103 in total—were compiled from current and former prisoners, private collections, and the CPA’s own permanent collection, and were made in six of the state’s 15 prisons.

Some of the pieces, such as those created by inmate Michael Seidman at Connecticut’s Brooklyn Correctional Institution, are made from typical art materials like colored pencils and ballpoint pens. Seidman—who joined the program in January 2017—started out by sketching drafts for a puzzle website he planned to create once he was released.

Installation view of “How Art Changed the Prison.” Photo: Christopher E. Manning, courtesy of the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.

Greene recognized Seidman’s artistic talent and encouraged him to expand his body of work, convincing him he was creating not just puzzles, but vibrant works of art. The project culminated in a series of intricate puzzles—including three-dimensional works—that require viewers to unpack with an answer key. Seidman—who recently stopped making art after developing carpal tunnel syndrome—is due to be released soon.

Meanwhile, other inmate artists used quotidian items they found around their cells to make their work, such as Ramen noodle wrappers, toilet paper, soap, tape, Q-tips, and floor wax. One artist, Edward Schank, designed a three-dimensional self-portrait by weaving together 1,374 Ramen wrappers to create Self Portrait Jewelry Box (2016).

Installation view of “How Art Changed the Prison.” Photo: Christopher E. Manning, courtesy of the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.

The CPA—originally named the Prisoners’ Friends Society—was founded in 1875 in Hartford by a group of social reformers, including Samuel Clemens (better known as Mark Twain), who was on the program’s board. The Prison Arts Program was conceived in 1977, making it one of the country’s oldest of its kind. The program also holds its own exhibition every year called the Annual Show.

The artists receive 60 percent of proceeds from sales of their work to their inmate accounts; 25 percent goes to a fund to pay for postage to return Annual Show artworks to families; and 15 percent goes to the Commission on Victims’ Services Compensation Fund.

The CPA and Greene’s hope is to change the prison environment into a healthier, more productive place.

“I am trying to help people create the calm and space needed to consider themselves,” Greene writes in the catalogue. “I am trying to help them create a life that is bearable and, moreover, rewarding.”

See more art from the exhibition below.

Installation view of “How Art Changed the Prison.” Photo: Christopher E. Manning, courtesy of the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.

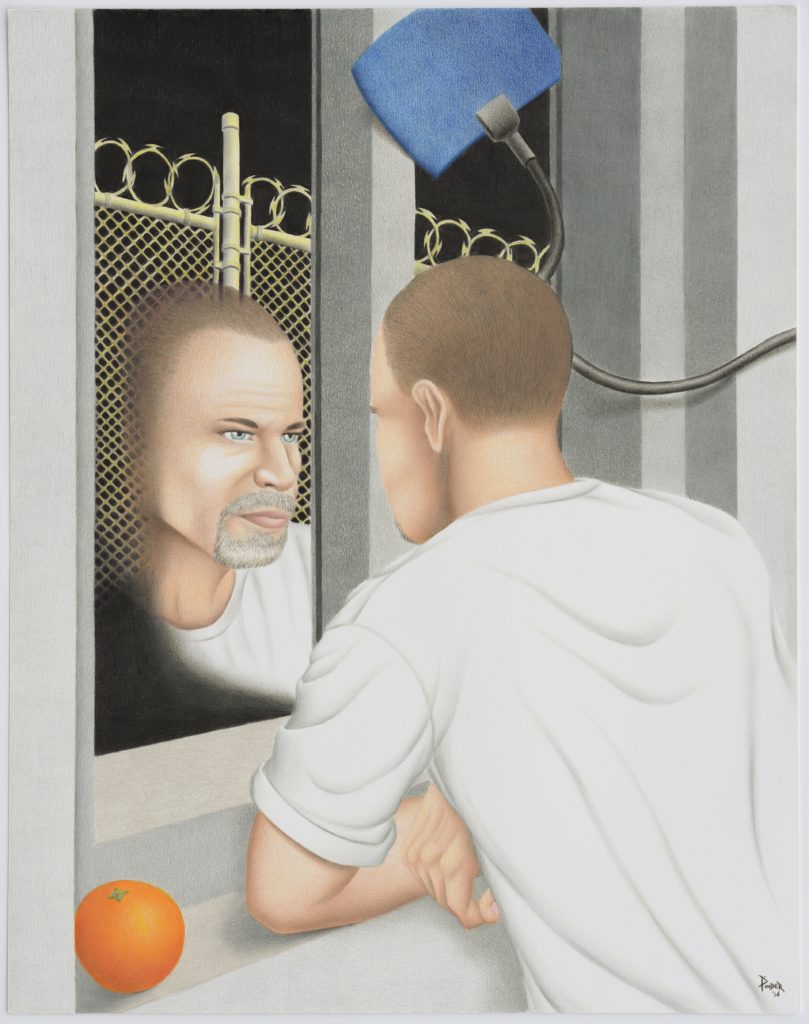

James Pinder, Outside Looking In (2016).

Installation view of “How Art Changed the Prison.” Photo: Christopher E. Manning, courtesy of the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.

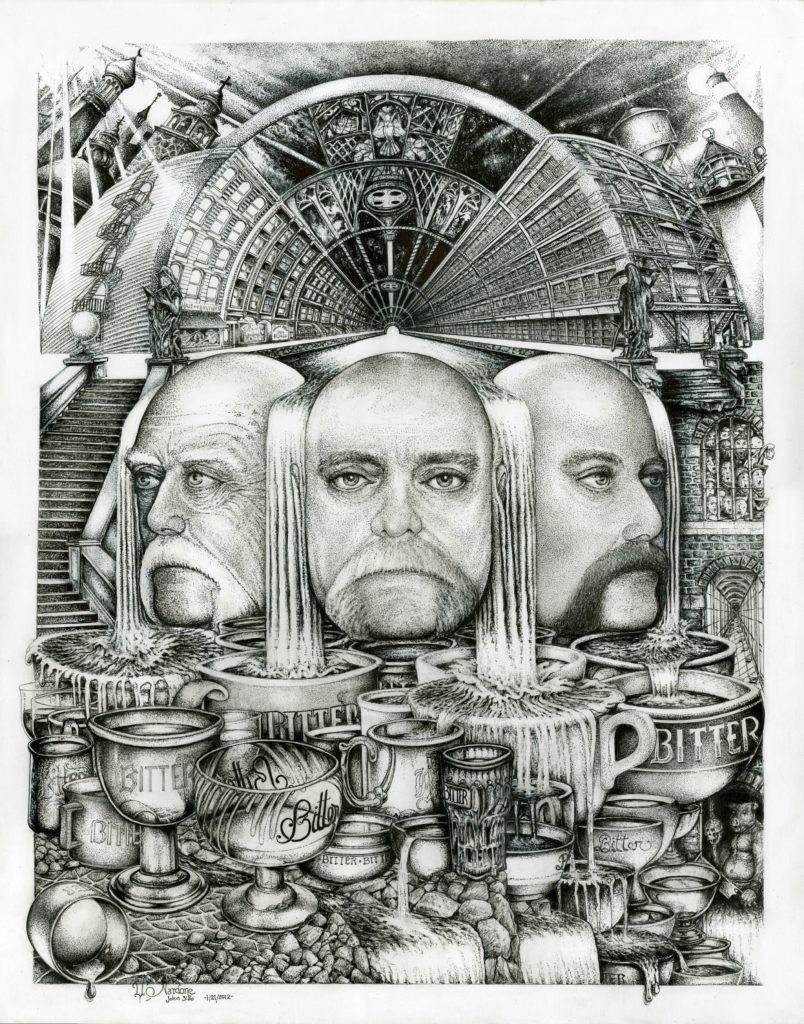

Vincent Nardone, Bitter Cup #36 (2011–2012).

Luis Norberto Martinez, Northern Flicker (2016). Collection of Jeffrey Greene.

Installation view of “How Art Changed the Prison.” Photo: Christopher E. Manning, courtesy of the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.

Lamont Thergood, The Day (2014). Collection of Jeffrey Greene.

Installation view of “How Art Changed the Prison.” Photo: Christopher E. Manning, courtesy of the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.

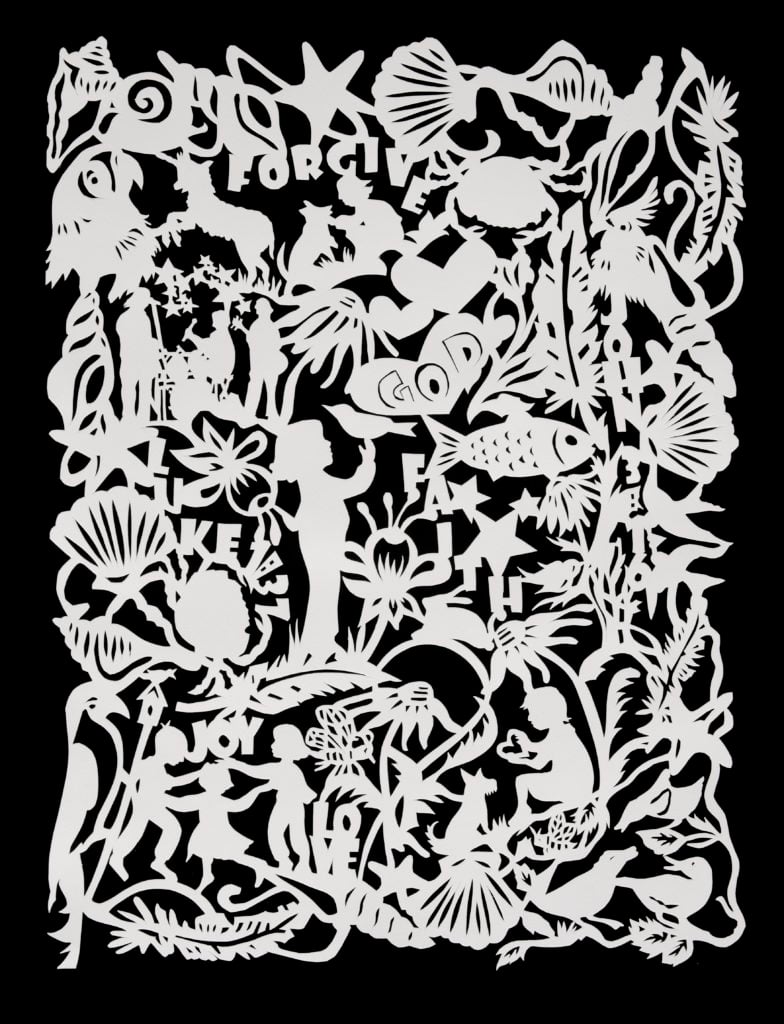

Nicholas Palumbo, FORGIVE (2015–2016).

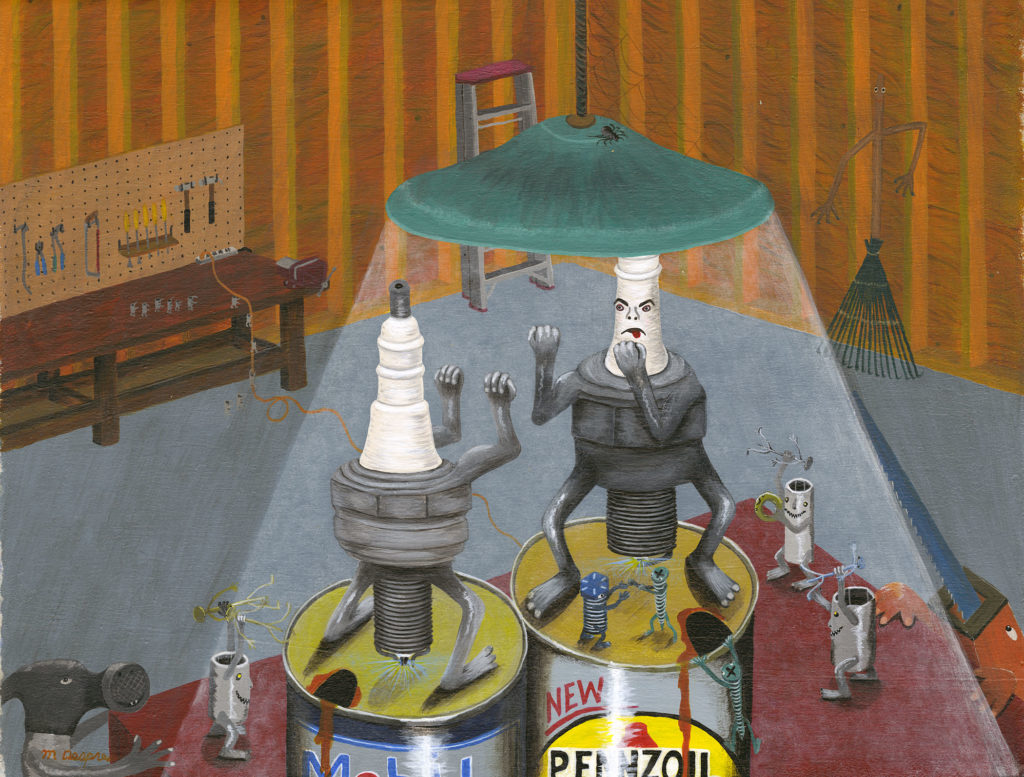

Mark Despres, Spark Plug Battle (2006). Acrylic on bedsheet. Collection of Jeffrey Greene.

Installation view of “How Art Changed the Prison.” Photo: Christopher E. Manning, courtesy of the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.

Installation view of “How Art Changed the Prison.” Photo: Christopher E. Manning, courtesy of the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum.

“How Art Changed the Prison: The Work of CPA’s Prison Arts Program” is on view at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, 258 Main Street, Ridgefield, Connecticut, January 27–May 27, 2019.