On View

The Internet Totally Changed What It Means to Make Art Today. A New Show Explains How.

The ICA Boston has organized an ambitious exhibition tracing the web's influence on art from 1989 to the present.

The ICA Boston has organized an ambitious exhibition tracing the web's influence on art from 1989 to the present.

Taylor Dafoe

In 1989, Tim Berners-Lee developed the World Wide Web while working at a particle physics laboratory in Switzerland. That invention, more than any other over the past 30 years, has transformed culture as we know it. But so far, museums have been slow to grapple with the web’s influence on art. In fact, an exhibition opening next week at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, is touted as the first major museum show ever devoted to the way the internet has shaped contemporary art.

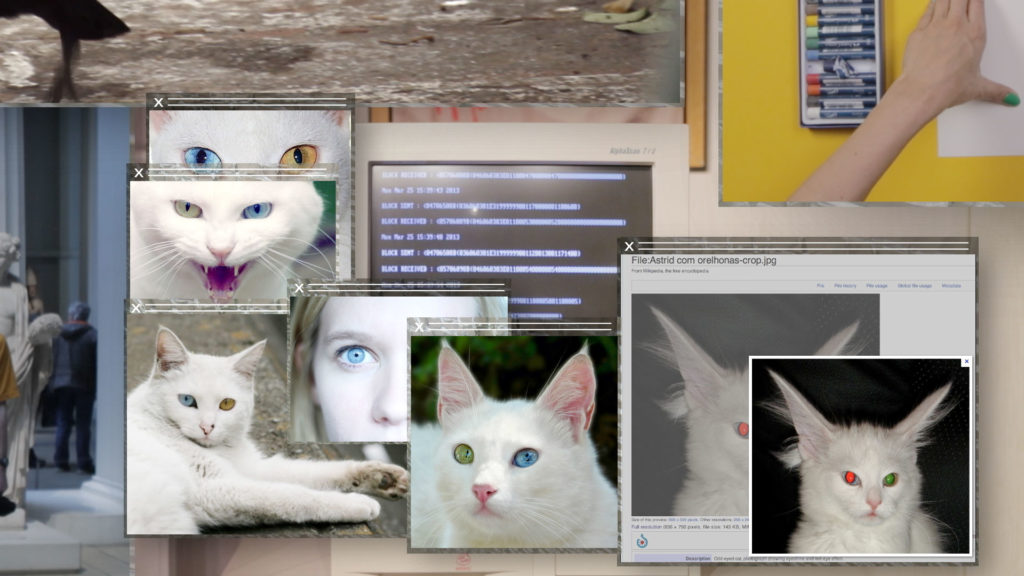

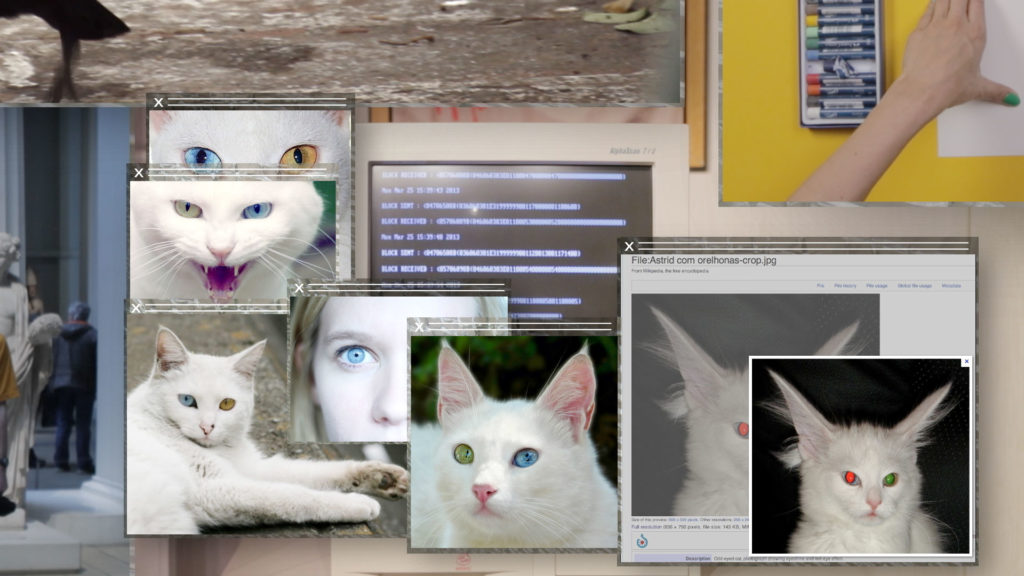

The wildly ambitious exhibition, “Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today,” brings together work by more than 60 artists, including Harun Farocki, Ed Atkins, Pierre Huyghe, and Cao Fei. It includes work in a vast variety of media, ranging from the digital (video essays by Hito Steyerl and Camille Henrot, a virtual workstation by Sondra Perry) to the analogue (Thomas Ruff’s blurred pictures of web-sourced porn, paintings by Albert Oehlen and Laura Owens).

“We’re thinking of the Internet as a social construct,” says the ICA Boston’s chief curator Eva Respini, who organized the show with newly promoted assistant curator Jeffrey De Blois. “We define it as a set of relationships that have changed everything about our culture—how we eat, how we date, how we shop, how we travel, and how we see.”

Lizzie Fith/Ryan Trecartin, Permission Streak (still), 2016. Courtesy the artist, Regen Projects, Los Angeles, and Sprüth Magers. © Lizzie Fitch/Ryan Trecartin.

Bound to be a crowd-pleaser is a new interactive VR project by Jon Rafman. In a room overlooking the Boston Harbor, viewers will don goggles and proceed through an eight-minute-long virtual journey, in and out of water, through a post-apocalyptic world.

Appropriately, the show extends outside of the gallery walls as well. The exhibition was the impetus for a sprawling exploration of art and tech unfolding at 14 Boston-area cultural organizations all winter. Meanwhile, Olia Lialina and the collective HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN? will present custom projects on the museum’s website for the duration of the show.

Jon Rafman, View of Harbor (2017). Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Matthew Monteith. © Jon Rafman.

The show poses a variety of knotty questions: How has the way that information circulates online changed the way we understand it? How has the internet changed our relationship to our own bodies? How has it transformed conversations around identity?

But perhaps the most difficult question for curators was a practical one: How can a museum effectively tackle these issues, given that many of the works included are nonphysical? How do you make an exhibition about art that is not meant to be shown in a white cube, and in many cases questions the efficacy of institutional systems altogether? Is it even possible to make a cohesive statement about the impact of something so large and diverse?

“This is not a show of technology… it’s a show about technology,” Respini says. “The Internet has now been around long enough that we can take a step back and examine how it has changed the production of art as well.”

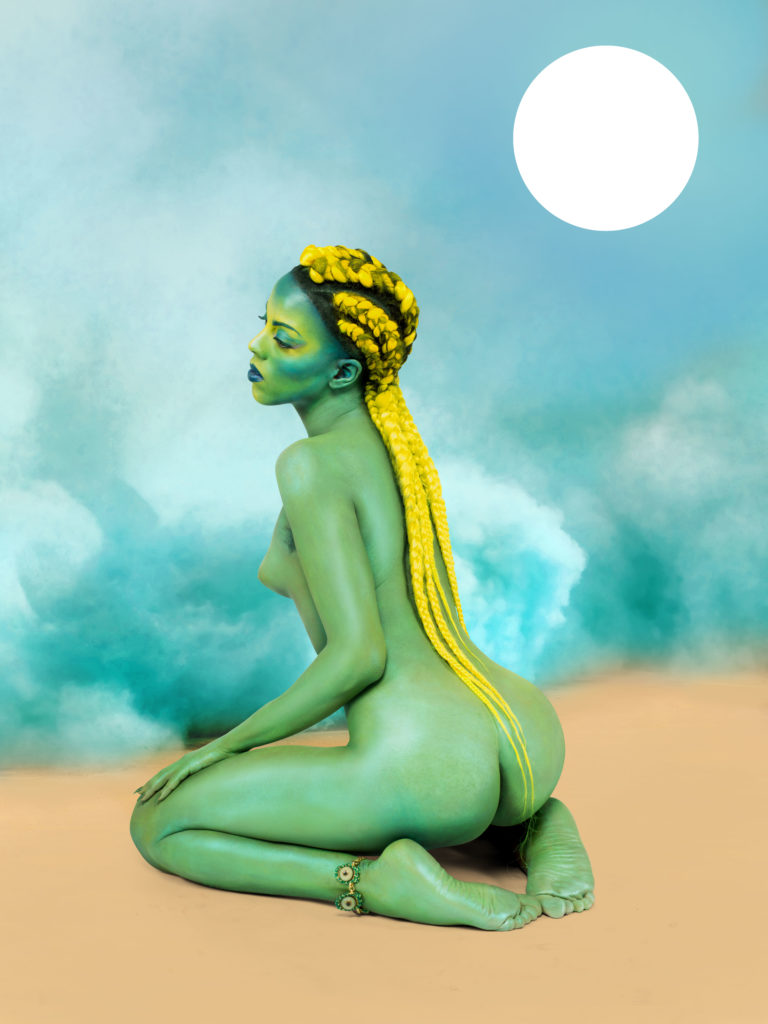

Juliana Huxtable, Untitled in the Rage (Nibiru Cataclysm) (2015). Courtesy of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. © Juliana Huxtable.

The show begins in 1989, in part because it was the year the Internet was birthed. Obviously computers, and even versions of the internet, existed before then, and indeed influenced art. But for Respini, 1989 “represents a defining contemporary moment. It’s the year that the World Wide Web was invented, yes, but ’89 was also a moment when, one could argue, globalization began. The fall of the Berlin Wall, Tiananmen Square, the first satellite sendup into space for GPS—it all happened then.”

Globalization is a theme that threads through the entire show, which includes artists from 21 different countries. “We didn’t want to assume a worldview of the internet that’s our own,” Respini says. “We tend to think of the internet as universal, but in fact, only 40 percent of the world’s population has access to it.”

Judith Barry, Imagination, dead imagine (1991). Courtesy of the artist and Mary Boone Gallery, New York. Photo by Adam Reich. © Judith Barry.

The show also traces changing perceptions of the internet as it began to infiltrate everyday life in unanticipated ways.

“For some, there’s a sense of the utopic possibility of the Internet—such as people like Nam June Paik, whose work previsioned a world of universal connectivity,” Respini notes. “Others have a more dystopian view of it, which I think is the prevailing view today—about algorithmic bubbles, about fake news, and people like the Yams Collective, talking about the role of activism and how we think everything is visible online—but in fact, this is not true.”

Amalia Ulman, Excellences & Perfections (Instagram Update, 27th May 2014), (Matching!!), From the series “Excellences & Perfections” (2015). © Amalia Ulman.

“Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today,” opens February 7, and will be on view through May 20, 2018. The ICA/Boston is located at 25 Harbor Shore Drive, Boston.