Art & Exhibitions

Why the Time is Right for a Joan Mitchell Revival, According to Baltimore Museum Curator Katy Siegel

The sweeping retrospective promises to show a side of the Abstract Expressionist that has gone unappreciated.

The sweeping retrospective promises to show a side of the Abstract Expressionist that has gone unappreciated.

Sarah Cascone

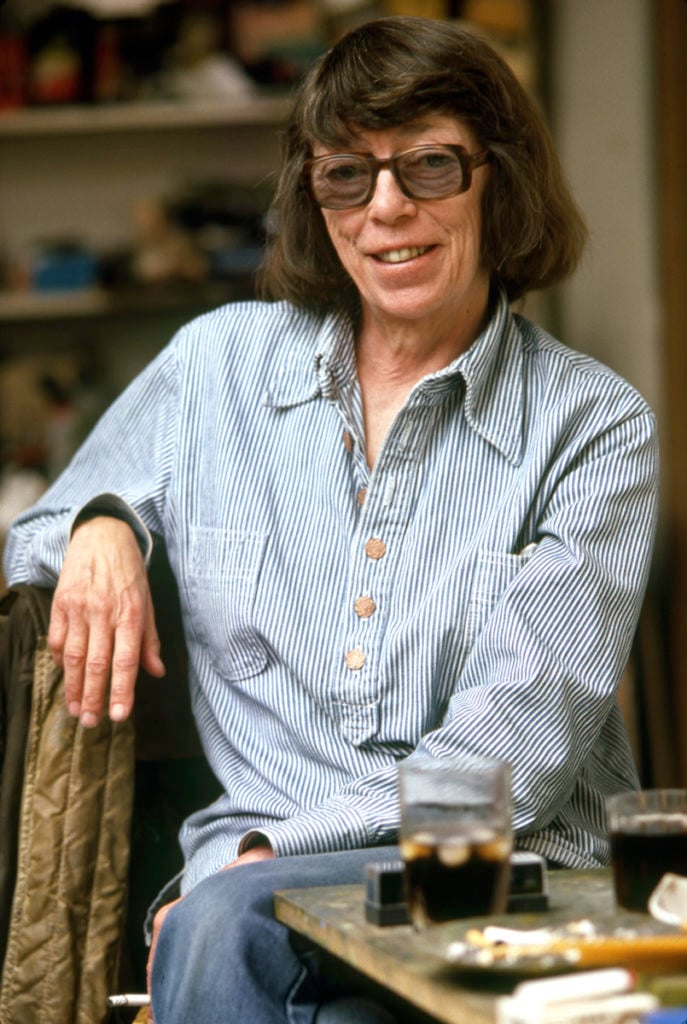

The celebrated Abstract Expressionist Joan Mitchell (1925–1992) is getting a major retrospective courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Art and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, starting in 2020. Organized by the BMA’s Katy Siegel and SFMOMA’s Sarah Roberts, the show will mark the first survey dedicated to Mitchell in the US in almost two decades, and promises to open an exciting new chapter in the reevaluation of her achievement as a major painter.

“It’s not like she’s an undiscovered artist who people didn’t see,” Siegel told artnet News. Yet even in her case, the curator suggests, there is work to be done to correct the record. “Joan Mitchell was working at an enormously high level for four decades, and people didn’t quite get it because she was a woman. I think people are ready to recognize her greatness.”

The show features 125 artworks including rarely seen paintings and works on paper, tracing the arc of her career from the early years in New York to large-scale multi-panel works made later on in France. As an important member of the New York School, Mitchell achieved the type of success that eluded many of her female peers, becoming immediately recognized for her artistic talent. She has been somewhat eclipsed by her male counterparts in the decades since—but that may be changing.

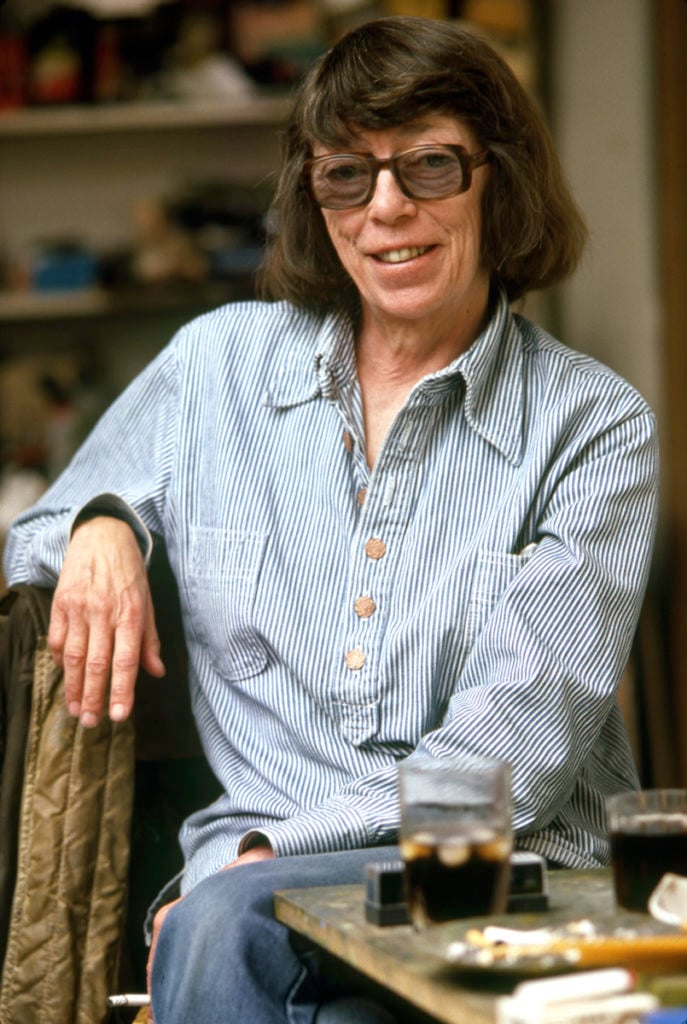

Joan MItchell, Bracket (1989). Courtesy of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

The announcement of the upcoming retrospective coincides with a dramatic uptick in market interest in Mitchell. According to the artnet Price Database, her record at auction is $16.6 million, set just last month at Christie’s New York by Blueberry (1969). David Zwirner gallery recently took over representation of Mitchell’s estate from New York’s Cheim & Read, just days before the new auction record was set.

Ahead of Art Basel in Basel, running through this weekend, Bloomberg reported that galleries were expecting to move as much as $70 million in Mitchell works at the fair. That estimate seems credible: According to reports, Hauser & Wirth placed Mitchell’s 1969 canvas Compostion with a European collection for $14 million; Lévy Gorvy of London and New York has sold Untitled (1959), which had an asking price of $14 million; and Zwirner sold a third Mitchell, Untitled (1958), for “in the region of its asking price,” which a fair representative said was $7.5 million.

Joan Mitchell, Untitled (1959). The painting, which had an asking price of $14 million, was sold at Art Basel in Basel by Lévy Gorvy of New York and London. Photo courtesy of Lévy Gorvy.

“It’s great when women and people of color get what they deserve,” Siegel said of the recent commercial interest. “It’s too bad that it so often happens after they’re gone. I wish it happened earlier.” The show has been in the works since 2015, well before the current surge in Mitchell’s prices.

In their research, Siegel added, she and Roberts found, while speaking with art institutions and experts around the country, that “there is just a enormous collective energy and feeling of good will and excitement around Mitchell.” She believes that this wide-ranging scholarly reassessment is the driving force behind the market’s newfound recognition of Mitchell’s importance.

“She is the last great, great artist of that generation who hasn’t been fully recognized or given her due. That’s partly because painting was out of fashion, but also because there’s been a really sexist and racist situation, where it was thought that big painting was being made by big white men,” Siegel said. “It’s really important that we’re able to see paintings now by people who are not the same 20 white men.”

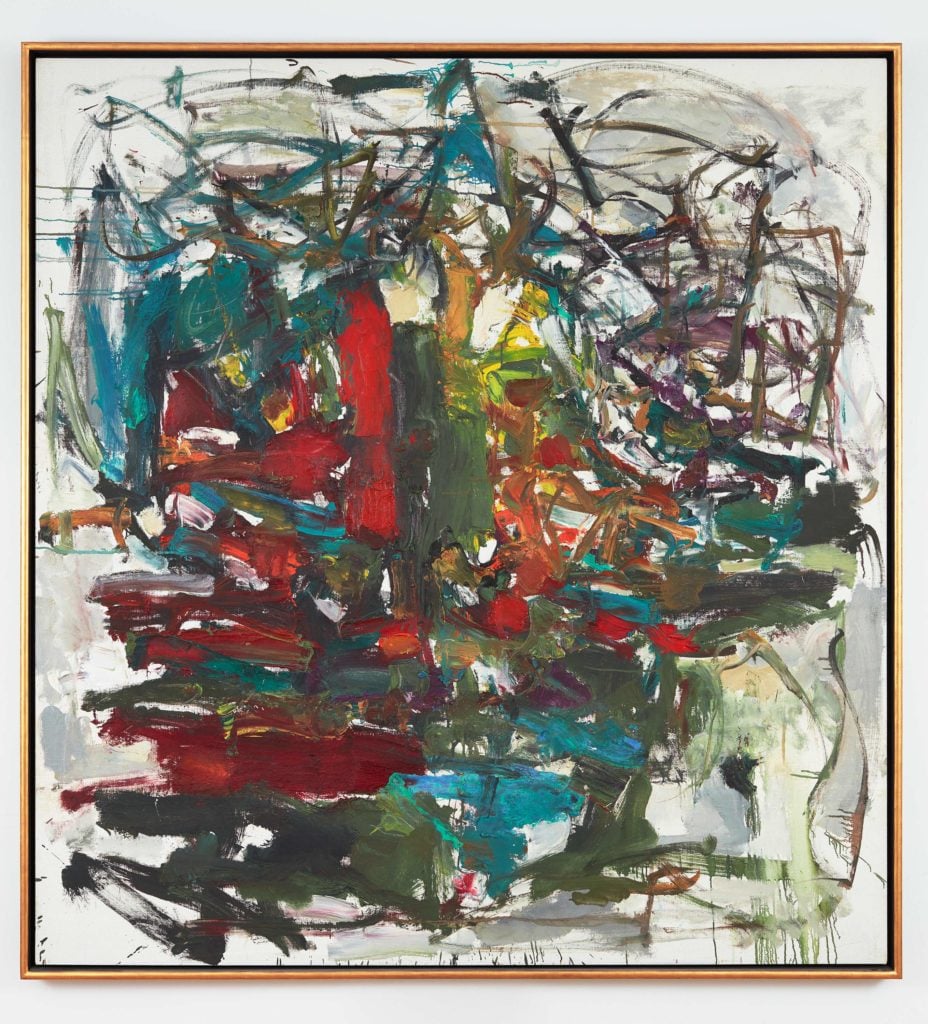

Joan Mitchell, East Ninth Street (1956). Photo by rocor via Flickr Creative Commons.

Mitchell’s reputation also suffered, according to Siegel, because her work wasn’t conceptual, and focused instead on more everyday, approachable themes. “We’re coming to a place where we can say that people can be brilliant intellectuals and artists without being conceptual,” she explained. “Music, poetry, feeling love for friends, dogs—the things that moved Mitchell, we are more open to valuing again.”

The BMA/SFMOMA show is Mitchell’s first US retrospective since “The Paintings of Joan Mitchell” at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art in 2002, a show that went on to appear at the Birmingham Museum of Art, the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, and the Des Moines Art Center.

Overseas, the artist was the subject of a 2015 retrospective at the Kunsthaus Bregenz in Austria that traveled to the Museum of Ludwig in Cologne.

The upcoming exhibition will open in Baltimore before touching down at SFMOMA in September 2020 and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York in February 2021. It will be double the size of the Whitney show.

Highlights are set to include major works such as the three-panel canvas Bracket (1989), which has been on prominent view at SFMOMA since its reopening in 2016.

Joan Mitchell, Mon paysage (1967). Photo by Margnac via Flickr Creative Commons.

“One of the great surprises of the exhibition will be how fresh the work from the last 25 years of her life looks,” said Siegel. “A lot of the artists of her generation died early… Her work continued to develop, but it seemed out of fashion at the time.”

“The way art history was being written, no one wanted to see what your later work looked like. People wanted to see the first thing that was innovative or trendy and then they were onto the next thing,” she added. Now, audiences are becoming more willing to examine the full scope of an artist’s career. For Mitchell, that means late canvases “filled with color and experiment and athleticism,” said Siegel. “She was an amazing athlete, a competitive ice skater, diver, tennis player… it really looks like it could have been made yesterday!”

The curators have also secured important loans such as East Ninth Street (1959), from the collection of the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art; and the abstract French landscapes Mon Pasage (1967) and No Rain (1976), from the Fondation Maeght in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France, and New York’s Museum of Modern Art, respectively. Such masterworks will be supplemented by Mitchell’s sketchbooks, a selection of archival photographs, and examples of other less-well-known facets of her career.

“With the pastels, the works on paper, the collaborations with poets, the small paintings that have almost never been shown, the transitional paintings between the huge masterworks that people are more familiar with, people are going to be amazed by the show and what it means to see Joan Mitchell in the fullness of her dimensions,” Siegel predicted.