On View

‘Hobbit’ Author J.R.R. Tolkien Didn’t Just Write About a Magical World—He Painted It, Too. See His Fantastical Artworks Here

"Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth" is on view now at the Morgan Library & Museum.

"Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth" is on view now at the Morgan Library & Museum.

Sarah Cascone

It’s hard to imagine a world without Harry Potter or Game of Thrones, but we might be living in it if it weren’t for J.R.R. Tolkien. The author is widely credited with giving birth to the modern fantasy genre through his realm of Middle-earth, the setting for his best-selling books The Hobbit, which came out in 1937, and its sequel trilogy The Lord of the Rings, published in 1954.

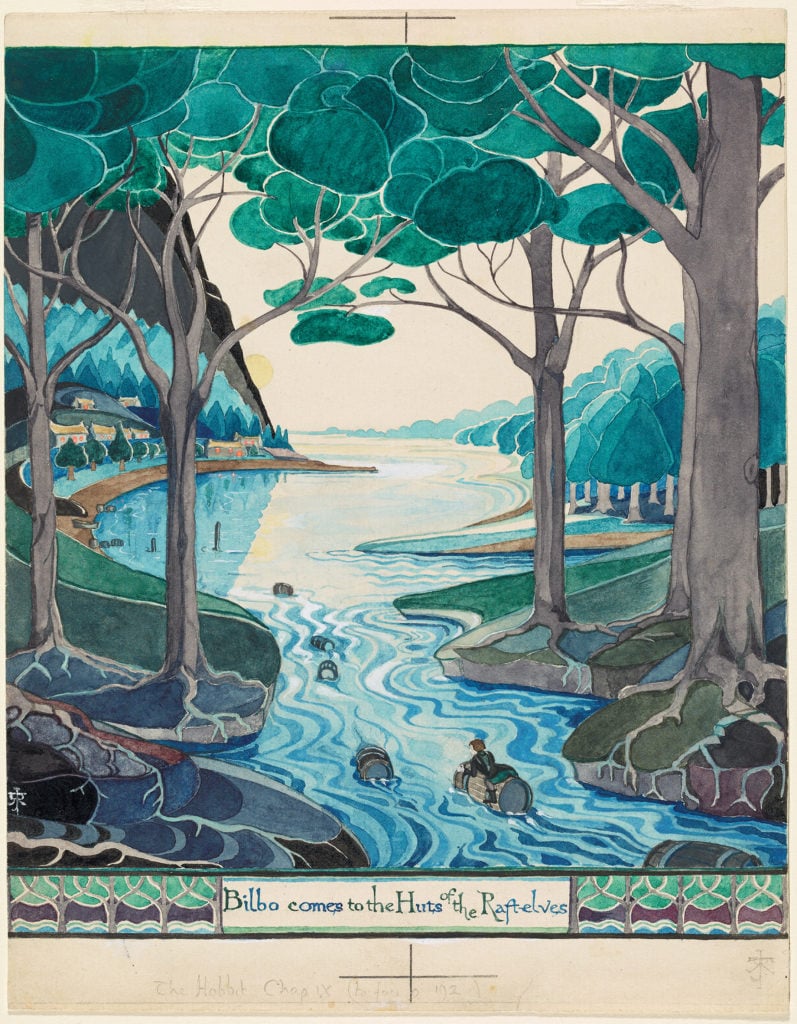

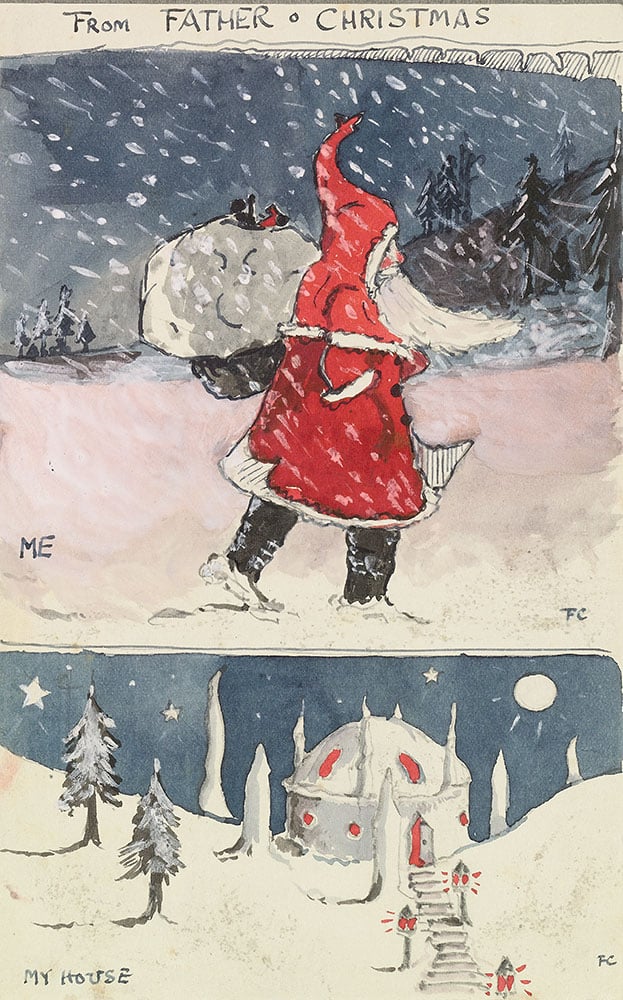

Tolkien’s creative genius, however, extends far beyond his capabilities as a story teller. He was also a talented artist and mapmaker who illustrated his own writings. (A trained linguist as well, Tolkien created Middle-earth to provide a history to go along with his invented languages of Elvish and Orcish.) Now, the author’s artistic prowess is on full display at New York’s Morgan Library & Museum in the new show “Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth.”

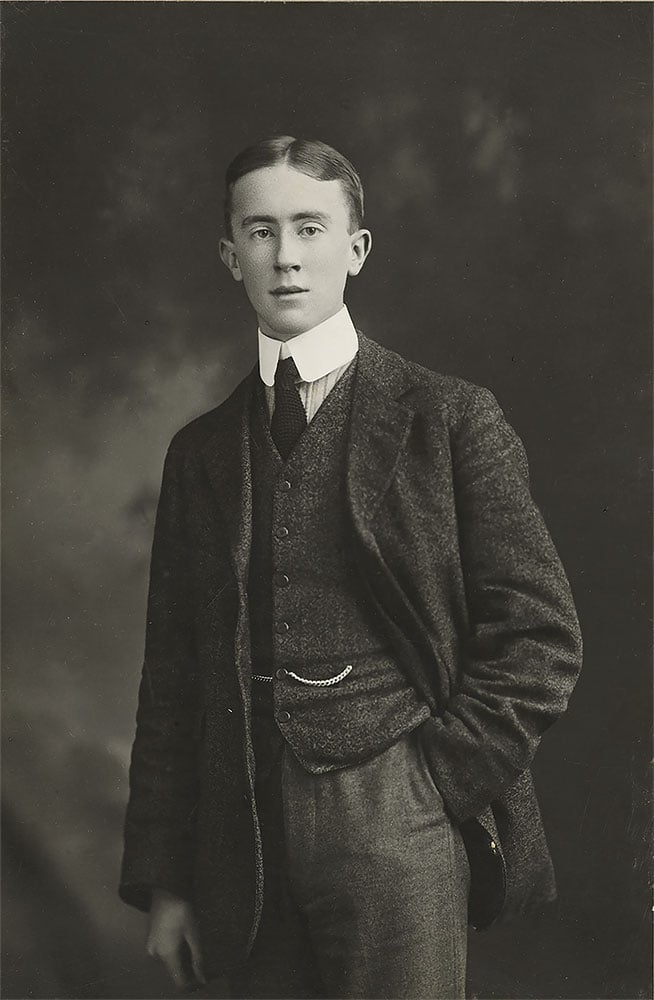

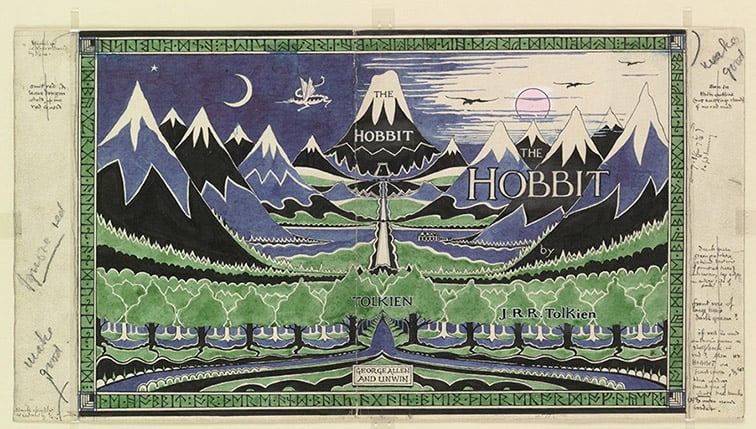

The exhibition, which originated at the UK’s Bodleian Library at Oxford University, features the largest selection of Tolkien-related materials ever displayed in the US. It includes childhood photographs of the author, who became an orphan at age 12, the final draft of the original dust jacket for The Hobbit, paintings of scenes from his books, and the original watercolors that became the cover art for the Ballantine-published box set of Lord of the Rings that was published between 1973 and 1980.

“The textual and visual creation of Middle-earth went hand in hand for Tolkien,” said exhibition curator John T. McQuillen during a preview of the show. “To see the actual materials that began it all is really stunning. You see the story taking shape.”

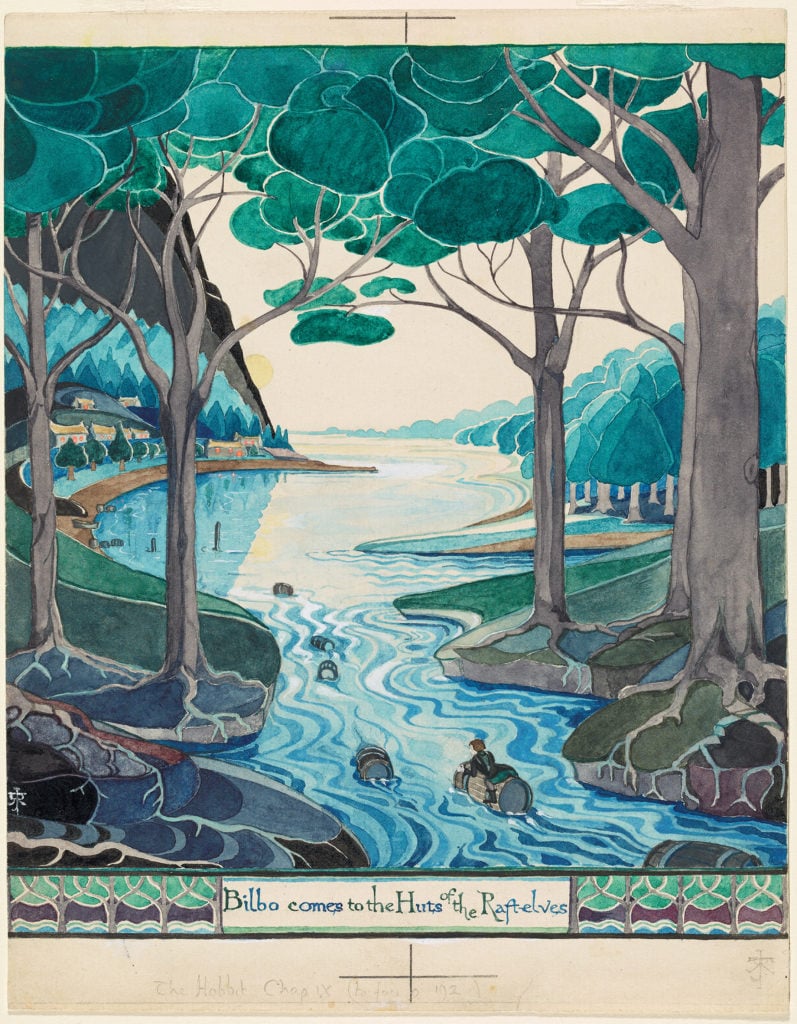

J.R.R. Tolkien’s first map for The Lord of the Rings (circa 1937–49). Courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries, ©the Tolkien Trust 1992, 2015.

There is Tolkien’s well-worn map, depicting the geography of Middle-earth, from the hobbit’s home in the Shire—inspired by Tolkien’s own childhood in the Birmingham countryside—to far off Mordor, overrun with evil. There’s also an intricate chart tracking each character’s whereabouts on a day-by-day basis, as Frodo Baggins, Aragorn, and Gandalf the Grey each go their separate ways in their quest to destroy the One Ring.

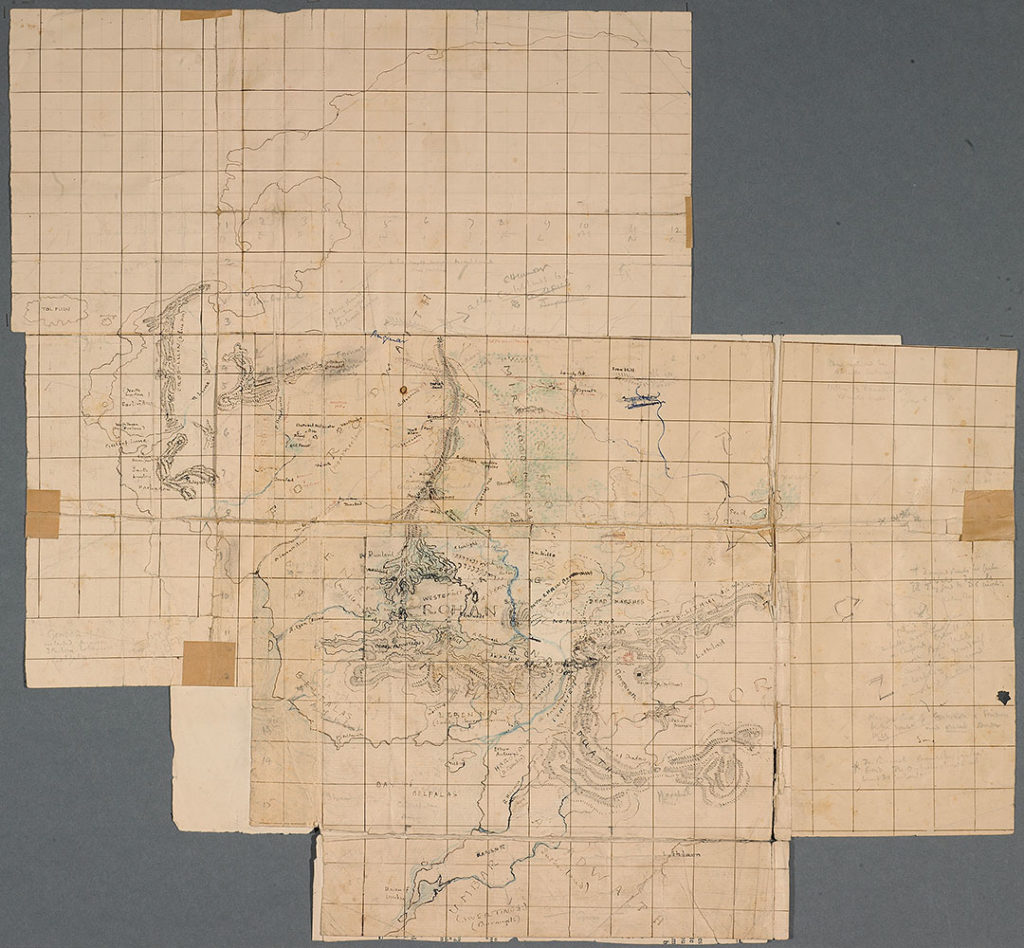

The show also provides glimpses into Tolkien’s personal life. There’s a portrait of his wife, Edith Bratt, alongside a paragraph noting that their romance was the inspiration for the love story of Beren and Lúthien, mentioned in Lord of the Rings and told in full in The Silmarillion. Plus, there’s adorable missives “from Santa Claus” to the couple’s children, written by Tolkien in a shaky hand (it’s cold at the North Pole, after all!).

J.R.R. Tolkien (1892–1973), Father Christmas drawing of “Me” and “My House,” (1920). Courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries, ©the Tolkien Estate Ltd 1976.

Tolkien’s children were the original audience for The Hobbit, and they were apparently less than pleased to have their bedtime story shared with the public. Luckily for the rest of us, their father ignored their objections and gave the world one of the greatest fantasy stories ever told.

“His sort of world creation is not, I don’t think, matched by George R.R. Martin, or even J.K. Rowling,” McQuillen said. “The history of his setting goes far beyond anything that either of them in their narratives, I think, accomplished, or even maybe aimed to do.”

Even those who consider themselves intimately familiar with the epic tale of Frodo and the One Ring will likely learn something about the series, especially through notes that reveal Tolkien’s initial plot plans. For instance, Treebeard, the kindly Ent who meets Merry and Pippin in Fangorn Forest, was originally intended to be a bad guy, in league with the fallen wizard Saruman. And Gandalf the Grey was supposed to be named Bladorthin—a wise revision if there ever was one!

Edith Bratt, aged 17 (1906). Photo by the Victoria Studio, 201 Broad Street, Birmingham, courtesy of the Tolkien Trust, ©the Tolkien Trust 1977.

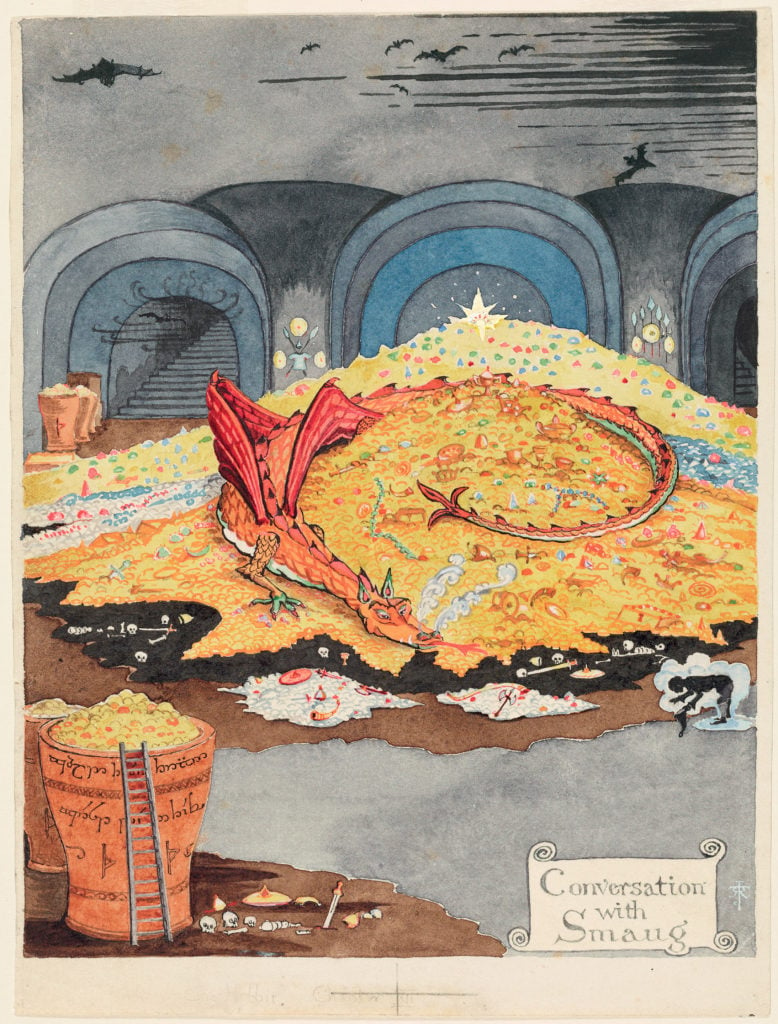

Surprisingly, Tolkien was quick to denounce his skills as an artist. “They are my own, I fear, and with the exception of the jacket, bad,” he wrote of the illustrations in the first edition of The Hobbit.

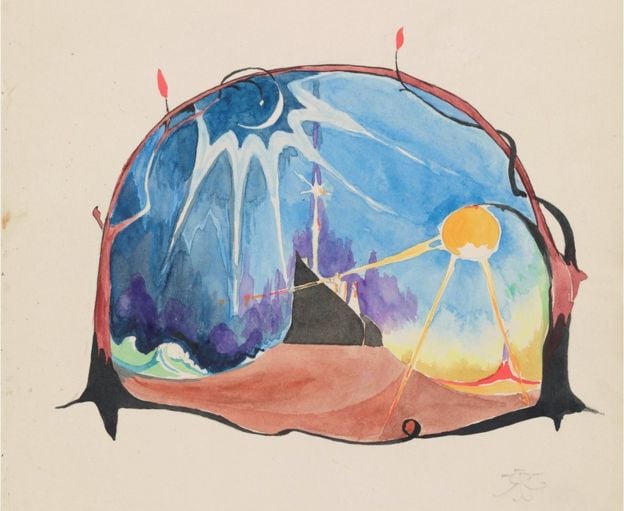

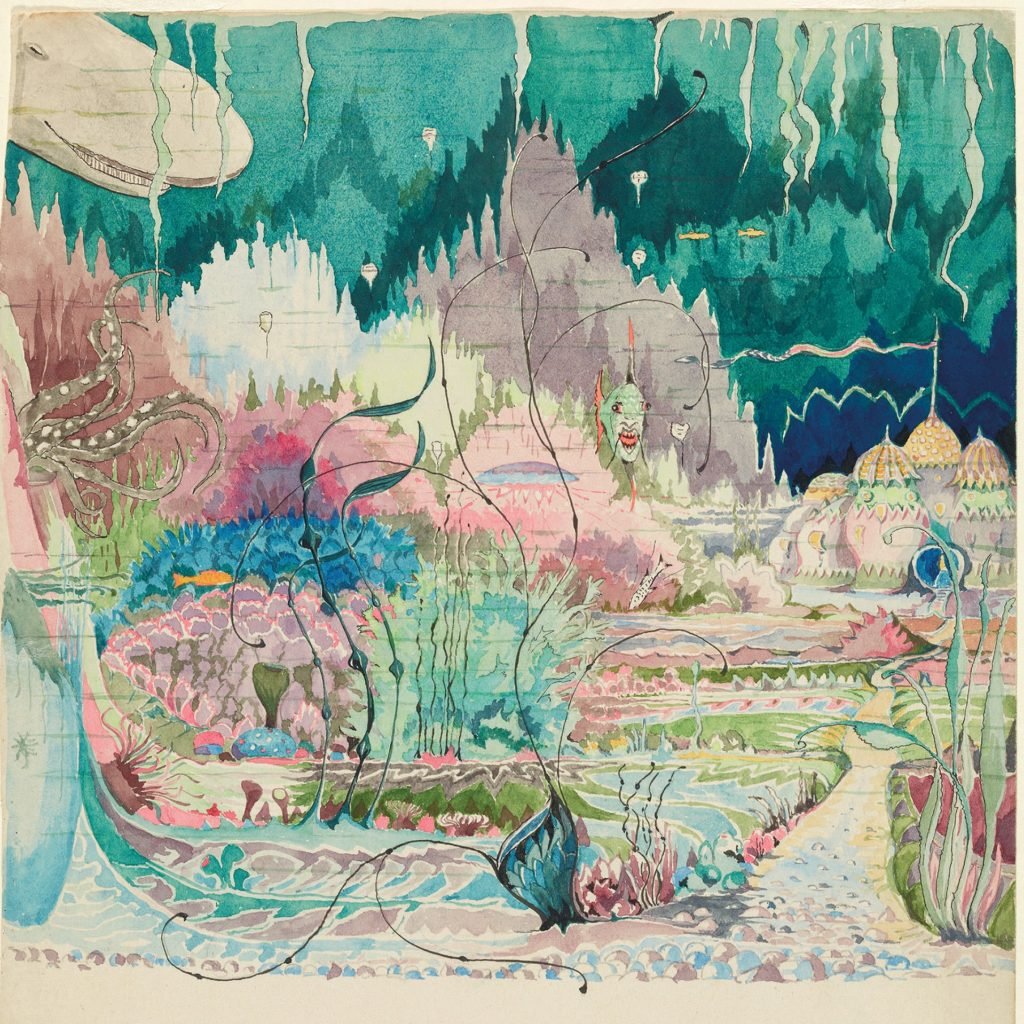

Nevertheless, the show’s biggest discovery is undoubtedly Tolkien’s artistry, from the intricate doodles he drew on the newspaper while contemplating crossword clues, to the almost abstract fantasy drawings that he made independently of Middle-earth in a sketchbook he called The Book of Ishness.

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hill: Hobbiton-across-the Water (1937), which appears on the cover of the Ballentine Books edition of The Lord of the Ring: Fellowship of the Rings. Courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries, ©the Tolkien Estate Limited 1937.

Together, the works on view “show Tolkien’s artistic abilities and his willingness to experiment with different style,” said McQuillen. “I would place his work alongside that of Beatrix Potter, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, and Maurice Sendak in the famed halls of children’s literature.”

See more works from the exhibition below.

J.R.R. Tolkien in 1911. Photo by the studio of H.J. Whitlock & Sons Ltd., Birmingham. Courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries, ©the Tolkien Trust 1977.

J.R.R. Tolkien, Conversation with Smaug, a watercolor illustrating a scene from The Hobbit. Courtesy of the Tolkien Estate.

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Shores of Faery (1915), an illustration for The Silmarillion. Courtesy of the Tolkien Estate.

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Gardens of the Merking’s Palace, an illustration for his novella Roverandom, written in 1925 and published in 1998. Courtesy of the Tolkien Trust.

J.R.R. Tolkien, dust jacket for The Hobbit with the author’s notes. Courtesy of the Tolkien Estate.

J.R.R. Tolkien, watercolor of an eagle. Courtesy of the Tolkien Estate.

A J.R.R. Tolkien fantasy landscape (circa 1915). Courtesy of the Tolkien Trust, ©the Tolkien Trust 2015.

“Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth” is on view at the Morgan Library & Museum, 224 Madison Avenue, New York, January 25–May 12, 2019.