On View

‘Bodies Can Be Our Own Borders’: Artist Julia Chiang on Making Art About Invisible Forces Within Us, From Sneezes to Anger

The artist discusses marriage, motherhood, and art-making ahead of her new solo exhibition.

The artist discusses marriage, motherhood, and art-making ahead of her new solo exhibition.

Ariana Marsh

A lot has changed in the six years since Brooklyn-based artist Julia Chiang first showed her work at Tokyo’s Nanzuka Gallery. After taking time to focus on motherhood and raising her two daughters, the artist is now returning to the space with a vibrant new solo exhibition. Called “Pump and Bump,” the show is a colorful exploration of the body and the invisible forces that roil it—from anger to tears to a simple sneeze.

“I’m constantly thinking of how things within us can be mimicked outwardly,” Chiang explains. “The violence we create, the love we share, the boundaries we make—it all starts from these tiny cells, and how they move, grow, push, explode, and come together.”

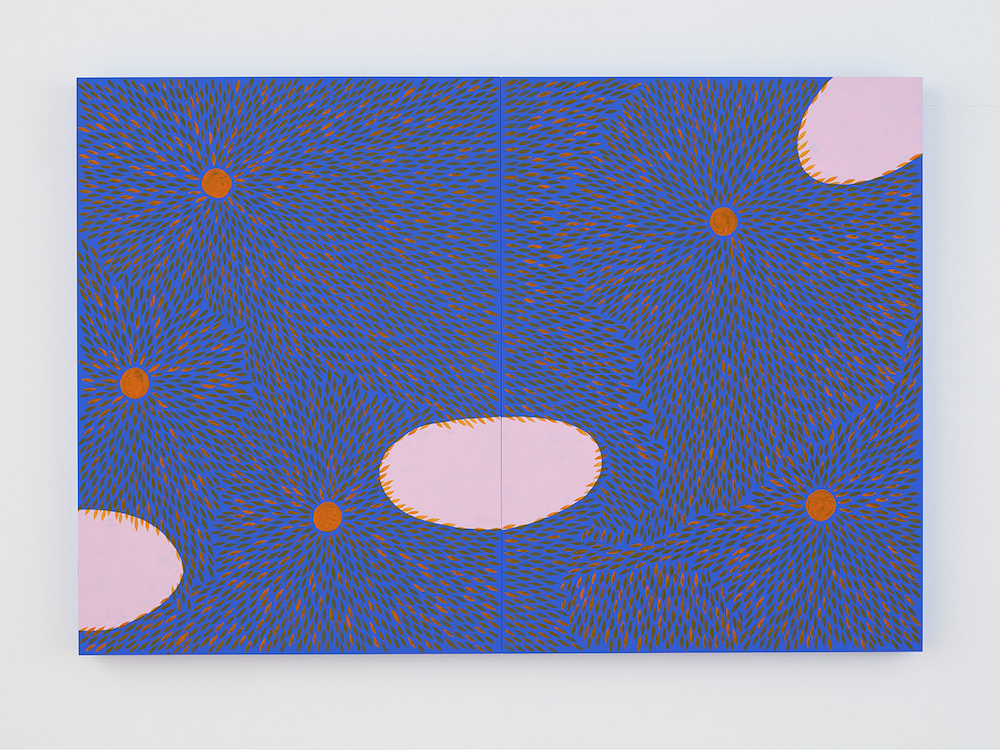

The show includes a selection of paintings and ceramics featuring Chiang’s signature repetitious style, in which tiny petal shapes blanket surfaces like cells. Her color palette—reds, blues, and purples—are inspired by her interest in contemplating the body from the inside out.

“I feel like if what you make can even just gets someone to pause and walk away with something, that’s a good thing,” Chiang says. “There’s this weirdness where people don’t even pause anymore, so if they stop to look, I’m pretty psyched.”

Chiang speaks with artnet News about the inspiration behind her show, how becoming a mother shaped her work, and the role art plays in her marriage to art-market superstar KAWS.

Tell me about how the show came to be.

It’s been an ongoing conversation since the last show I had at Nanzuka Gallery six years ago, when I was pregnant with my first child. At that time, I was entering the unknown of becoming a mom, and Shinji Nanzuka [the gallery’s owner and founder] was saying, “When you feel ready to show again, let me know.” That’s rare, right? Over the years, he took pieces of mine to fairs and kept me in the loop. When I had just the one kid, I could work regularly, part-time. Maintaining the work didn’t feel as difficult, in a way. But when our [newest] little one arrived, she really threw me off—she was really hard as a baby. I always kept working, but the idea of committing to a show on my own just didn’t seem like a good idea. So finally, when I got more into the regularity of the craziness, I decided to commit to doing this show.

Do you have any special relationship to Japan? Why did you choose to return to Nanzuka and show in Tokyo rather than, say, New York, where you live?

I love Japan but I haven’t shown there from a particular relationship to the place. I met Shinji though my husband [Brian Donnelly, also known as KAWS] when I traveled with him there years ago. He asked to see my work, and to visit my studio, and it started from there. I had only known of a few Japanese artists he showed, but after time with him, and meeting some of his artists, it felt like we were old friends. The opportunity for my own show came about six years ago. He’s always been supportive of me in the sense that he knew I wanted to take time to be a mom and just make work slowly and figure things out.

Julia Chiang, Summer Hot (2019). Photo courtesy Nanzuka gallery.

How does the work in this show compare to your last exhibition there?

It’s similar to what I was doing before, just smaller scale. I painted and did a lot of ceramics and made a lot of functional stuff, just because I wanted to keep everything regular. If you step out of the studio for too long, when you get back in, everything is weird and the groove is just gone. I wound up giving a lot of gifts to people and making stuff for my kids. It’s a total luxury that I can choose to raise my kids and be there when I need to be or want to be and also juggle my own studio schedule. The majority of people in this country have no choice. Our country is not one that supports the belief in time needed with raising families. In that way, I feel super fortunate. Not to say it’s easy—it’s kind of [like] trying to figure out a way to maintain two full-time jobs without the secure benefit of one full-time job.

What was the inspiration and drive behind “Pump and Bump”?

I don’t aim to represent anything specific. One of the magical things about art for me is not knowing what somebody’s intention was in what they made, and walking away with my own understanding of it. But with everything I do, I’m constantly thinking about our bodies internally and externally—how everything functions within and how it’s expressed outwardly. I’ve always connected with behavior, with the way people interact physically in real time, how they clash and come together. If something’s happening externally, whether it’s arguing, crying, or war, it’s manifesting inside of us, too. If our bodies can be our own borders for all our inside stuff, we can be each other’s boundaries for all the physical stuff around us. Our blood can’t just go through our skin, it’s enclosed within us. If people explode with anger, there are physical constructs to control it.

So does each painting within the exhibition reference an emotion or emotional reaction?

I’m not making a painting and thinking, “This is going to portray what happens when you get punched in the face.” It’s not so specific. In general, I think about cause and effect regarding forces of nature. So, if you come at something with this much pressure, what could be a potential result of that? If you could see a sneeze from inside and outside, what might it look like? If you could portray what happens in your body when you’re having sex, if you could see all the things going on within two people, what might that look like? It’s not necessarily a specific emotional feeling, it’s more just imagining specific forces [more generally].

Julia Chiang, Bumpity Bump (2019). Photo courtesy Nanzuka gallery.

Tell me a little about your color theory. It informs so much of your work.

I’m drawn to blues and reds and purples a lot because I feel like they are part of our internal makings. Not that if you cut yourself open there’s all that rainbow, but if you bleed or if you bruise, these are very common colors. I feel like there’s kind of an extended rainbow of color when you think of all that comes out of us, so I usually start from that palette. Recently, I’ve been looking a lot at body scan images and medicine and drugs and the surreal, weird vividness in all of that. It’s really beautiful to me. They’re always strange—very saturated, very vibrant, and not really colors that you would normally think of when it comes to the body.

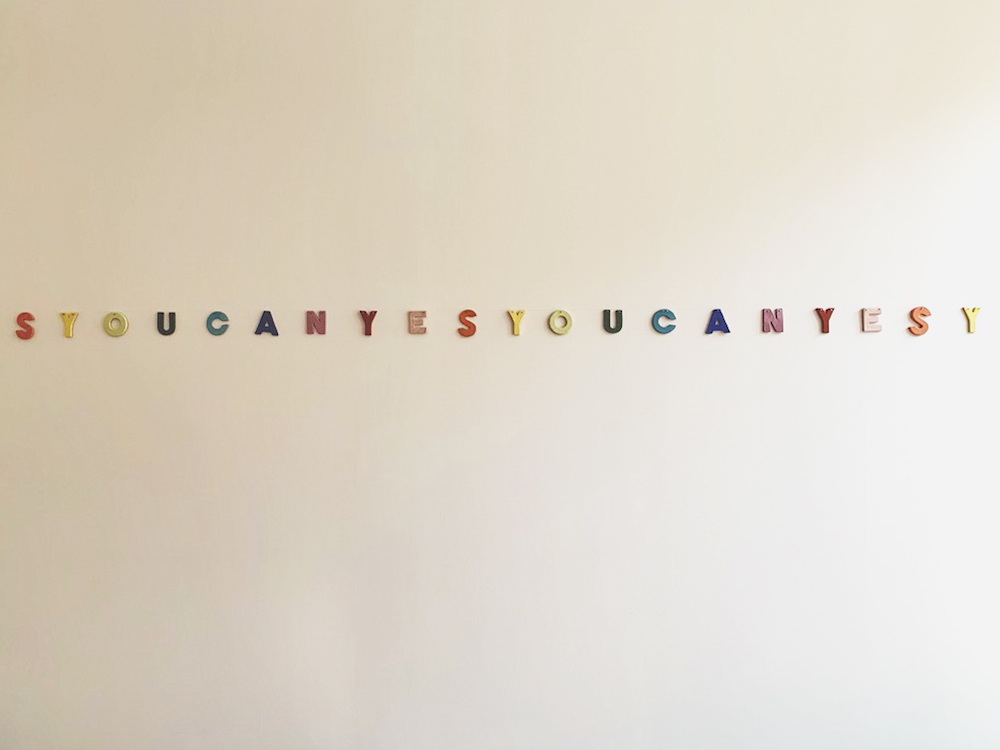

The phrase “Yes You Can” features prominently in your show. Where did that come from?

We’re in a climate where everything in the world seems like it’s falling apart and getting worse. It feels like there’s an overwhelmingly negative response to things: “No, it’s not gonna happen” or “You can’t do this, you can’t do that.” I felt there was this need—this physical need—to believe that things can change, that things can happen. When said over and over, the positive feels more like a need to believe, an attempt at convincing oneself almost. Now, more than ever, we could all use some convincing… at least I can. I also really related to the phrase “Yes You Can” in terms of managing work and family life and taking on the news. I just felt like it was really reflective of the times.

Why did you choose to display the phrase in ceramic letters?

I’ve always loved working with ceramics. It’s the material I’ve worked with the longest, and I’ve always loved it for its duality of being super fragile and super strong. I like the contrast of saying something loud and confidently with a ceramic letter that might potentially break as soon as you hang it on the wall, if you hit it the wrong way. They’re just very connected for me, the material itself and the install of the words.

Julia Chiang, Yes You Can (2019). Photo courtesy Nanzuka gallery.

What, to you, is the point of making art? Of looking at art?

I’ve just always loved making things. Itchy hands, you know? They can’t stay still. And looking at art—I’ve always loved seeing how people make things, what they make, and how they see. I remember as a kid going to the Met and just being blown away. I couldn’t believe hands made the things I saw, and I’ve always loved learning how people make the things they do.

You’re married to an artist. How does art factor into your relationship?

I mean we’re married, so we share it all. We talk art as much as we talk about everything else and we share a lot about what we’re making, though we work really differently. But yes, art is a big part of our family.

“Pump and Bump” is on view at Nanzuka Gallery, Shibuya Ibis bldg #B2F, 2-17-3 Shibuya Shibuya-ku, Tokyo, September 7–October 5, 2019.