“Why are we tolerant, and not intolerant, of suffering?” Julia Scher asks me over the thundering sounds of her installation at Esther Schipper Berlin on a recent afternoon.

The 64-year-old American artist rose to acclaim in the early 1990s for posing exactly these kinds of impossible, wide-angled questions. Speculative topics like the future of humankind in the face of artificial intelligence were still marginal issues then, but they appear potently relevant today Esther Schipper, where Scher’s breakout techno-landscape from 1998, Wonderland, has been faithfully recreated twenty years later.

On view until February 9, the soundscape hangs on the cusp of analog and digital technology and it feels, amazingly, like it hasn’t lost any of its currency in the passing decades. It also feels, worryingly, like Scher’s ominous musings on the future may have finally arrived.

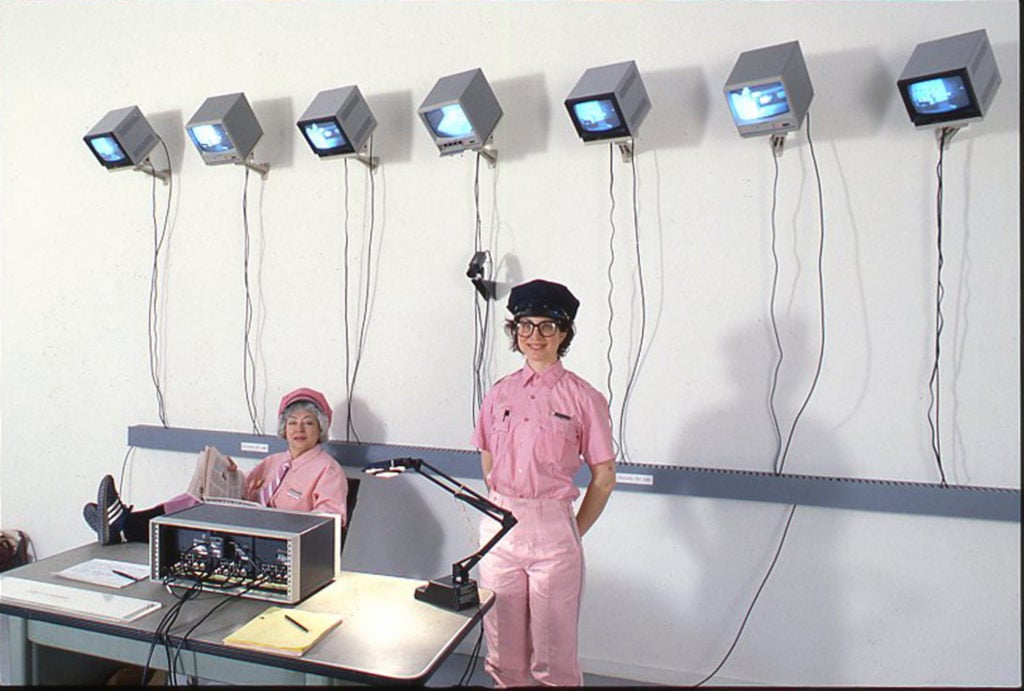

Exhibition view of Julia Scher’s Wonderland, Esther Schipper, Berlin, 2018. Photo: Andrea Rossetti.

Through the Rabbit Hole

Wonderland made its debut at New York’s Andrea Rosen gallery in 1998. As Scher puts it, the piece is still a fundamentally “New York work.” Indeed, it includes a towering portrait of a 10-year-old Lena Dunham and her sibling Grace Dunham, whose parents—artists Caroll Dunham and Laurie Simmons—allowed Scher to photograph them, as a favor to dealer Andrea Rosen.

The entire installation is child-sized, complete with tiny stools, desk, and candy scattered around. Children, who Scher calls “young innocents,” are among the most helpless victims of violence. But in Wonderland, things have changed. Scher has put the kids in charge.

“When being told to do all this shit by the Queen of Hearts in Alice in Wonderland, who eventually tells Alice ‘off with your head,’ Alice replies, ‘screw you—you’re just a pack of cards!’ In my version, she’s saying, ‘you’re just a bunch of bytes!’ She is defying the computerization of her life,” Scher says.

As viewers walk around the installation, fun-house mirrors alter the reflections of their bodies while Scher’s voice directs their movements. The work tempts visitors to take selfies, an aspect of its development that delights Scher (since it was made well before camera phones). “I love technology,” she says as she takes out her phone and we snap a picture together. “I’m a total groupie.”

Lena by Julia Scher. Courtesy of Esther Schipper.

Her enthusiasm for digital technology is tempered by an ominous undertone, however. “There will be violence as we enter a world of new neural networks and new connections that were never before there,” she says.

“When people have to run away from a fire, the person who can run the fastest has a better chance of survival. In that sense, the way we’re built—our physicality—used to be a determining factor,” Scher says. But “strength could change in the future with the advent of artificial intelligence and body extension robot networks. But how will it change?”

“The hope is that brute strength won’t be necessary at some point, that it will drop away. But if we (humans) keep populating the Earth like this, how can you get equality, equity, and extensions for every person?” she says.

I ask her if she thinks our relationship to power is changing in civil society today. She seems encouraged not by the answer but by the question. “These are questions that humans ask, but these are not questions that artificial intelligence will ask. In your proposal, it’s great to see that you are a human!”

Scher, who is deftly avoidant of concrete answers, adds that she remains optimistic. “Maybe the human thing is over but, because I’m human, I have hope. I have trust though that technology will continue to move on,” she says. “If not by humans, technology will continue to do it itself.”

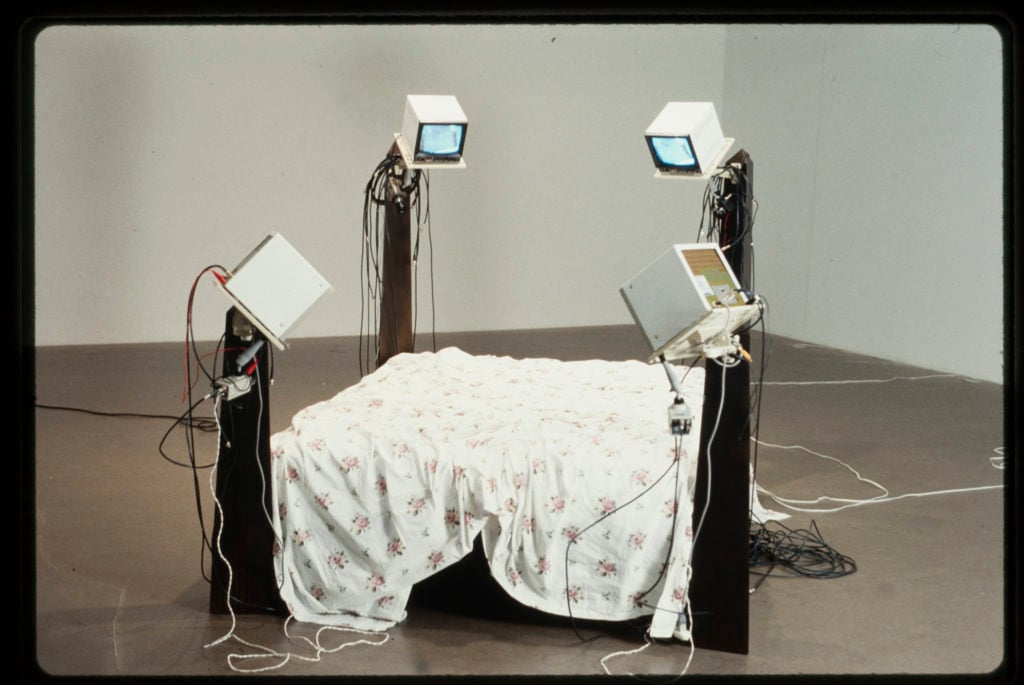

Julia Scher’s Guards, Hidden Camera at Frieze London 2018. Courtesy of Esther Schipper, Berlin.

Imagining the Future as Female

Scher’s female-centric installation, which draws reference both to a brothel and a teenage girl’s bedroom, conflates a surveillance society with the male gaze. Her baby pink security blankets, pink guard uniforms, and photographs of children in pink uniforms, who are portrayed as safekeepers, stir up tension between the realities of women, who tend to be over-observed in both public and private spaces. (Scher’s choice of pink comes from its history as the color attached to homosexuals in the Nazi death camps and later as the symbol of resistance and empowerment in the AIDS coalition ACT UP.)

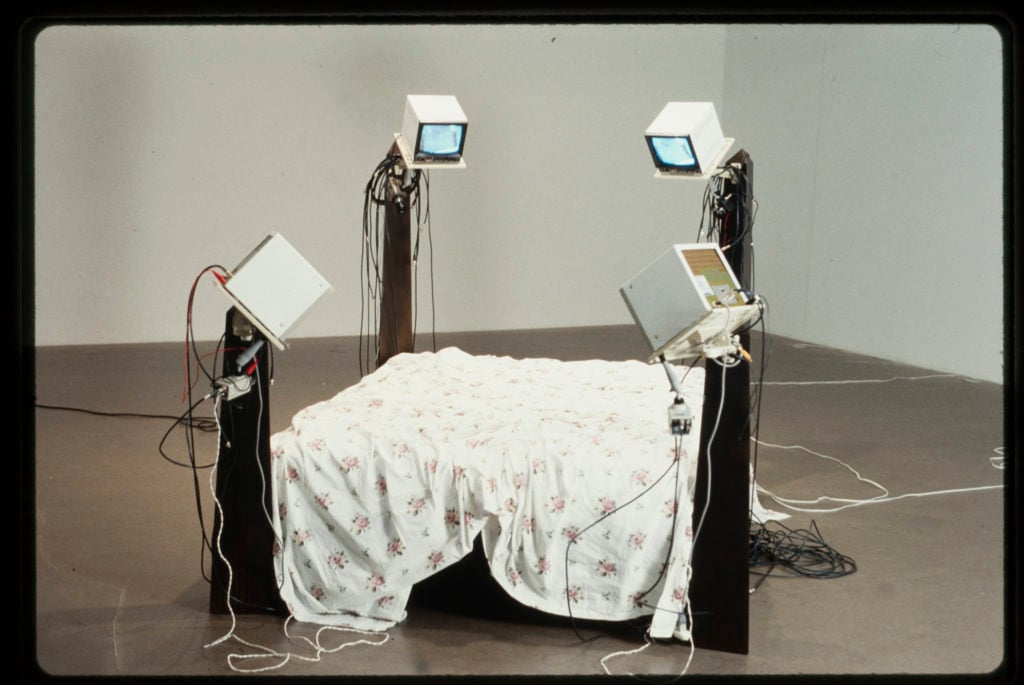

These are all ingredients in Scher’s vision of dystopian optimism, as is Mama Bed, a work from 2003 that features a bed and a leather whip, surrounded by cameras. Everything lingers around the boundary of being cute but also profoundly scary. “Is something really threatening if it’s sweet?” asks Scher.

Always There (1994) from Scher’s “Surveillance Beds” series. Courtesy of Esther Schipper.

Scher taught the first class on surveillance studies in the US at the Massachusetts College of Art in Boston. It’s no small wonder, considering her premonitions about the paradoxes of “smart” technology were eerily prescient (If this is a SmartRoom, why don’t the lights works!? calls out the installation, in doubt of itself.) Today, she’s a professor of multimedia and surveillant architectures at the Academy of Media Arts in Cologne, where she has lived for many years.

“Does a [‘SmartRoom’] mean that, without computers, we are in a DumbRoom?” Scher asks me, in another baffling question. “Are we paying more to be with artificial intelligence? Wonderland comes out of an alertness about what everybody already knew back in 1998: how devastating technology smells on one side, but how grateful we are for it on the other.”

I wondered if she could imagine the male gaze ever becoming outmoded, as technology may continue to change power relations. “Let me answer the question sideways first. My hope is that identification itself becomes more liquid, like it really is,” Scher says. “And my hope is that it the dominating gaze, used to force you into a shape, will be like some kind of plague—gone.”