Most summer gallery shows focus on presenting a broad swath of up-and-coming talent. But Kurimanzutto did something different: The Mexico City-based gallery traveled to London to present a tribute to a short-lived gallery that operated for two years in the mid-1960s. A version of the show will travel to Kurimanzutto’s recently opened New York space this fall, the gallery recently announced.

The lifespan of the artist-run gallery Signals was short, but its influence is long-lasting. The space showcased avant-garde works by European, Central, and South American artists, giving a global shot of adrenaline into the arm of London’s swinging art scene. But some good things are not meant to last: Signals shuttered in 1966, the same year TIME magazine officially declared London hip and happening.

David Medalla, Cloud Canyons (1963–2014), Image courtesy of the artist

and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City.

Co-founded by the Filipino-born artist David Medalla in an apartment when he was in his twenties, the gallery took its name from the kinetic sculptures of the Greek-French artist Takis. “Signals: If You Like I Shall Grow” was organized by the art historian Isobel Whitelegg and presented by Kurimanzutto across Thomas Dane Gallery’s two spaces in central London. (Kurimanzutto will return the favor when it hosts Thomas Dane in Mexico City next year.)

José Kuri, Kurimanzutto’s co-founder, first became interested in the historic gallery decades ago. His brother, artist Gabriel Kuri, had just returned from living in London in the 1990s and regaled José with tales of meeting Medalla and learning about the gallery’s radical and pioneering spirit.

“It was a gallery and it was also a gathering of artists working with a common idea,” Kuri says. “It reminded me of how we started our gallery, which was almost like a co-operative of artists.”

Looking Backward

The desire to pay tribute to pioneering dealers of the past has become something of a trend lately. Last October, Frieze London celebrated the legacy of A.I.R., the feminist artist-run art gallery that offered many now-prominent female artists their first shows in the ’70s and ’80s. And in May, Frieze New York presented a special section dedicated to the late, one-named art dealer Hudson and the legacy of his Chicago- and New York-based space Feature Inc.

Takis, Signal (1964), installation view of “Signals: If You Like I Shall Grow,” Kurimanzutto at Thomas Dane Gallery, London, courtesy of the galleries.

Is this impulse to look back prompted by the inexorable rise of the alpha gallery and the contemporary struggles of mom-and-pop shops? Kuri says his motivation is not so much nostalgia as a desire to look for lessons that can be applied by disillusioned dealers today.

“It’s more about revisiting the idea that there are other ways you can exist in the world,” he says. “If you compare it to how galleries are acting right now, it is becoming so corporate and business-orientated, going back to these very simple models where they shared this common energy is very inspiring for a gallery like ours.”

Pioneering Vision

Signals was one of the first galleries to show artists from around the world, from Venezuela to the Philippines to Brazil. “Can you imagine that in London in the ’60s?” Kuri asks. “That was very radical.”

The artist Takis is also central to the story of Signals, which was named after his series of kinetic works that reflected the rapid technological changes taking place in the ’50s and ’60s. The 1964 sculpture Signal, which features colored lights blinking on top of tall antennae, formed the centerpiece the London show. It was surrounded by works by artists including Lygia Clark, Otto PIene, Harry Kramer, and Hélio Oiticica, all of whom first made their London debut at the gallery.

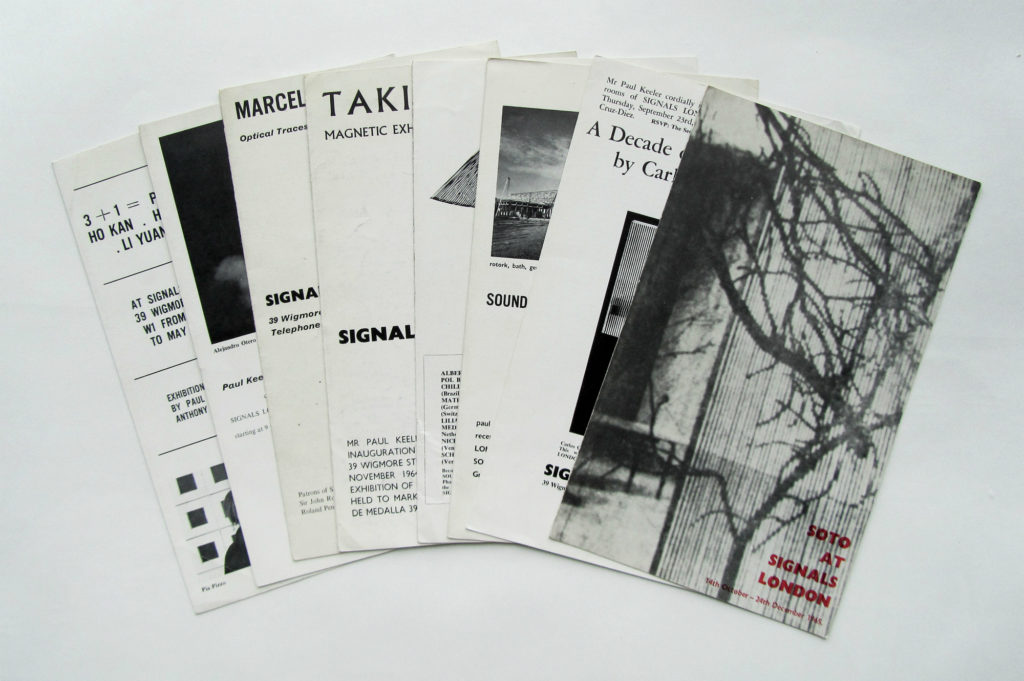

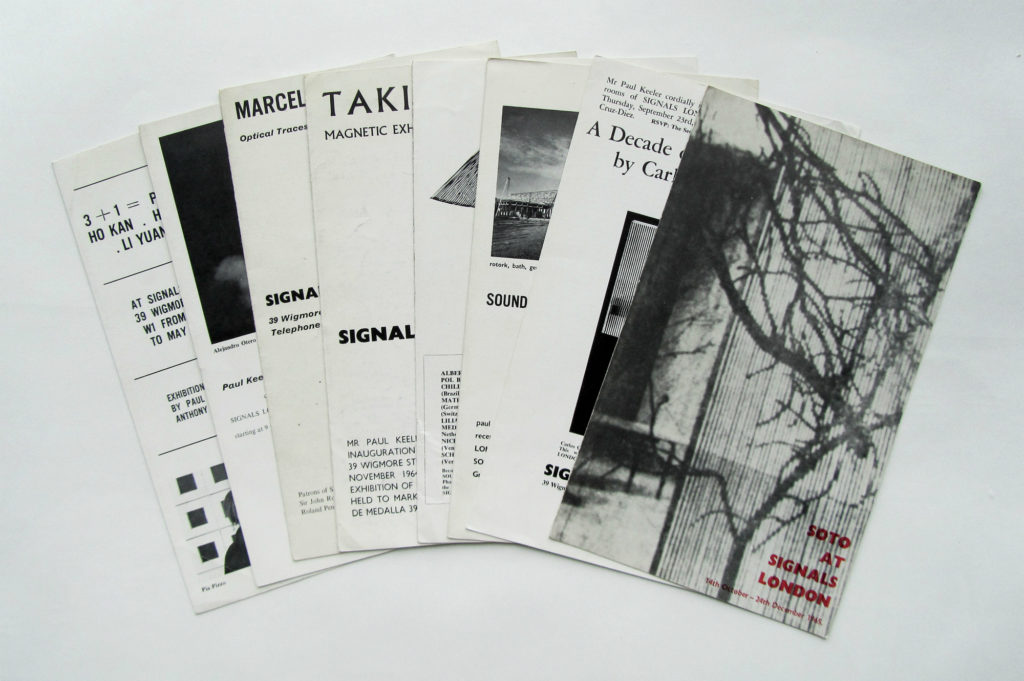

Signals exhibition pamphlets (1964–66). Image courtesy William Allen Word & Image, London.

Kuri is quick to credit the art historian Isobel Whitelegg for her original research on the history of Signals and the biographies of some of the more obscure artists who showed there. She also tracked down many of the elusive works in the show. One even turned up in a north London garage. “I am just a fan,” Kuri says. “She is the scholar.”

Whitelegg’s research revealed that Signals presented more than the kinetic and Constructivist art for which it is best known. “They were not just kinetic artists—they were conceptual artists,” Kuri stresses. He notes that David Medalla translated poetry that appeared in Signals’s magazine, known as the Signals Newsbulletin.

Gustav Metzger, film still from Auto Destructive Art, by H. Liversidge (1965).

Image courtesy Contemporary Films, Ltd.

That said, the most eye-catching works in the show are the kinetic ones, like Medalla’s Cloud Canyons (1963–77), a cluster of cylindrical towers overflowing with white foam. The sculpture was inspired by the artist’s memory of seeing New York’s skyscrapers disappearing into low clouds. The work, which Kuri describes as “seminal,” will travel to the New York version of the show in October.

“In London, we put in a lot of British artists; in New York, we will try to focus and go deeper into the more international relationships, between Medalla and [Signals co-founder] Gustav Metzger, between Lygia Clark and [Mexican painter] Mathias Goeritz,” Kuri says. British artist who were part of the Signals story included Ivor Davies, Kenneth and Mary Martin as well as Chinese-born Li Yuan-Chia.

Ivor Davies, Yellow Shadow (1965). Image courtesy the artist and Kurimanzutto, Mexico City.

Kuri hopes that artists from the Signals generation will begin to secure the museum retrospectives and surveys they deserve. He says that Tate Modern is working on “a big Takis show,” which the gallery has not officially announced, while a German museum director is interested in organizing a survey of the German artist Harry Kramer’s work.

Medalla, the Signals co-founder, also deserves a retrospective, Kuri says. (The globetrotting artist’s 1967 participatory textile work, A Stitch in Time, was included in last year’s Venice Biennale exhibition, “Viva Arte Viva.”)

As British politicians fixate on border controls post-Brexit, Kuri says: “London should feel proud. It is amazing it all happened in London in the ’60s. Hopefully, that will be interesting for New York to see.”

“Signals: If You Like I Shall Grow” runs through July 21 at Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

“Signals: If You Like I Shall Grow (Part II)” runs from November 13 to January 21, 2019, at Kurimanzutto New York.