The first show that Laura Hoptman curated after moving from the Museum of Modern Art to the Drawing Center last year asks a lofty question of the medium: Can drawing set us free?

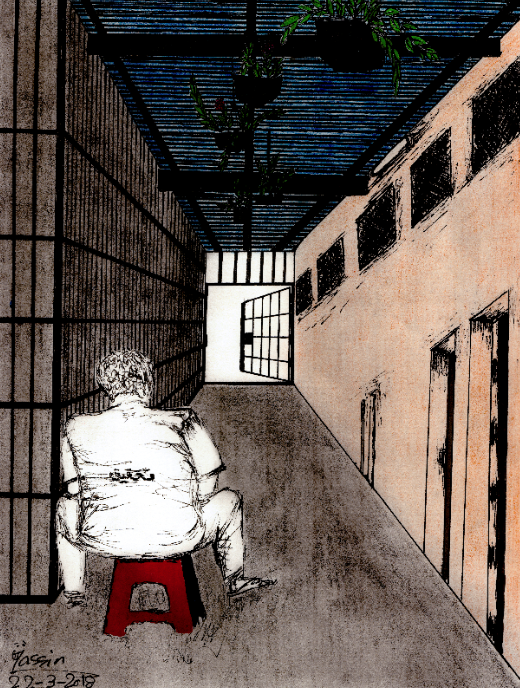

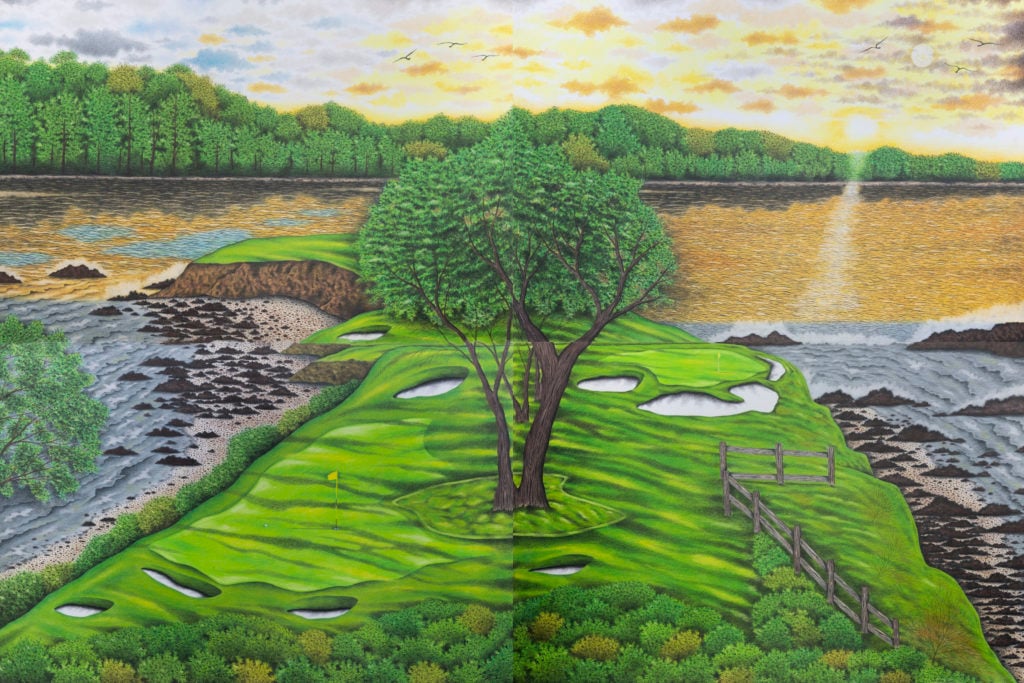

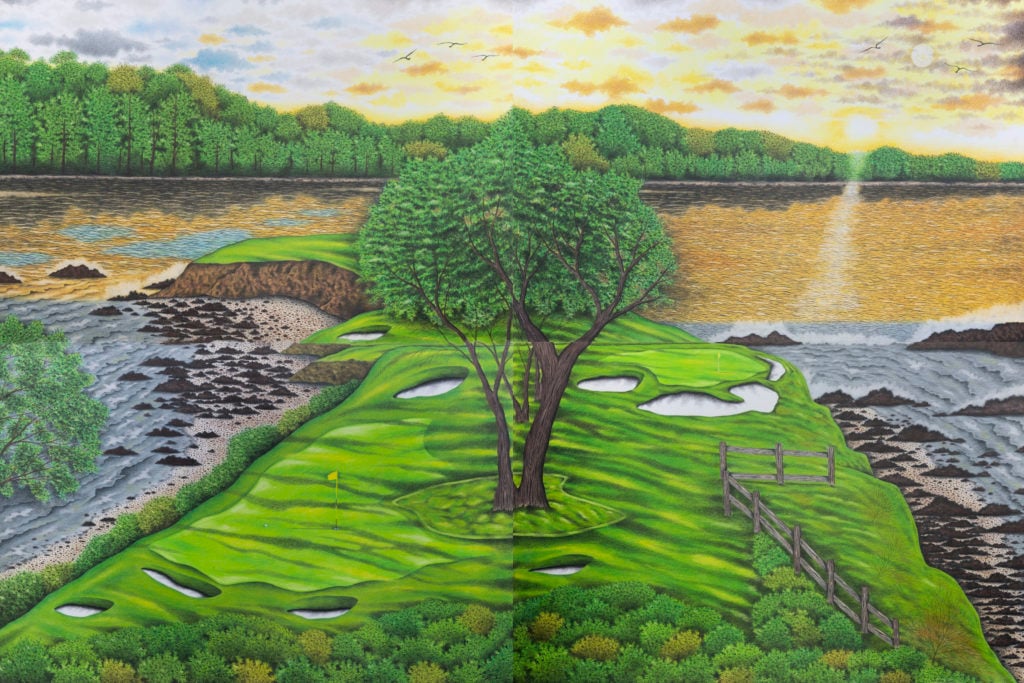

Actually, for one artist in the show, it did. Valentino Dixon was serving a life sentence for murder in the Attica Correctional Facility when he saw a photograph of his warden’s golf course and began drawing golf-scapes with colored pencils. After Golf Digest magazine profiled Dixon, reporters started investigating his conviction and found the evidence flimsy. Dixon’s daughter sold his pictures to help pay lawyers to reopen the case and, last year, a New York court vacated Dixon’s conviction and set him free.

Dixon’s drawings of golf courses are among the 150 works on view in “The Pencil Is a Key: Drawings by Incarcerated Artists,” open through January 5, 2020. But prison is only one means of confinement that the show considers. It also exhibits drawings made by artists in concentration camps during the Holocaust, in Japanese internment camps in the US, as well as greeting cards sent from the Gulag and detainee drawings from Guantanamo. Organized chronologically—from the French Revolution and the Jim Crow era, to South African apartheid and Pinochet’s Chile, up through the present mass incarceration plaguing the US—the show is also a crash course in 200 years of global calamity.

We spoke to Hoptman about how she tracked down the far-flung works, why she opted against showing so-called “prison art,” and how she navigated the sensitive issues around exhibiting work by both victims and criminals.

A drawing by Valentino Dixon. Courtesy of the Drawing Center.

This is your first show at the Drawing Center since you joined the museum a little over a year ago. Why did you want to make this your debut?

What I really wanted to do was start my tenure here with an exhibition that could not have been done anywhere else. And—this is a tall order, but I think we did it—I wanted an exhibition that in some way thematically proved how vital drawing is to people, just in general. And what’s more vital when you’re in extremis, you’ve lost your freedom, than to be able to express yourself through the medium of drawing? It makes sense to me and when I told my colleagues they were immediately like, “yeah we have to do this.”

My first impulse was to make the show thematic: We have to prove that drawing makes you free. That’s something we’d like to believe, but we’re not sure it’s the truth in every case. It’s a means of expression and a way to battle un-freedom, but it doesn’t necessarily make you free. It made Valentino Dixon free, I guess. But it was an unprovable concept, one that we loved, but it’s pie in the sky.

All the works in the show were made by artists during periods of incarceration. What other parameters did you set when you curated the show?

It’s not codified, but “prison drawing” is a thing and we knew from the get-go that that’s not something we wanted to look at, prison drawing qua prison drawing. I’ve seen wonderful exhibitions in the past of work made by people in prisons in the US, or in therapeutic programs like the one in San Quentin, but that was not what we wanted to do.

The parameters are to only look at people who were artists and/or became artists while they were in prison, and the reason is intentionality. We didn’t want to show involuntary artists’ work, work that wasn’t meant to be exhibited. A perfect example was a saved cache of drawings by children in Auschwitz. This was something we didn’t want to do, the kind of work that was done involuntarily. The second condition is everybody drew, the third is that all the work in the show was created in the moment when these artists were not free. So for the [Honoré] Daumier, it’s very specifically dated February 1833—it couldn’t have been in March, when he wasn’t in the clink.

What about when it came to the biographies of the artists? Were there any artists you wouldn’t have included based on the nature of the crimes they committed?

We had help from our colleague Nicole Fleetwood, a professor [of American studies and art history] from Rutgers whose area of expertise is precisely this, contemporary art done under circumstances of incarceration in US. We were asking what we thought were searching questions: Is it okay to put a political prisoner next to a murderer? Are people going to be upset? And she said, “first of all, you’re not judges, you don’t have any idea who’s a political prisoner or not, or what that even means because there are lots of different ways to cut that, and you should just stay within your expertise. You guys are curators of drawing, that’s what you know. Stay within that and you’re fine.” And she was so right. That’s what we tried to do. We looked for good and interesting drawings. To your question of biography, her rule of thumb was that it doesn’t matter.

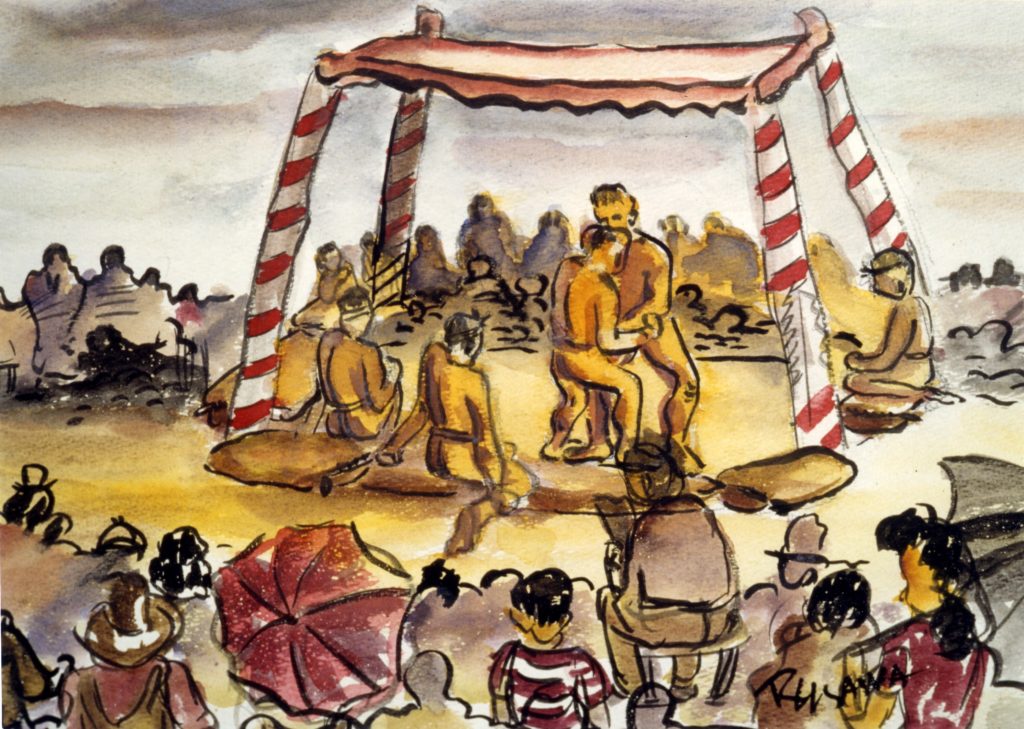

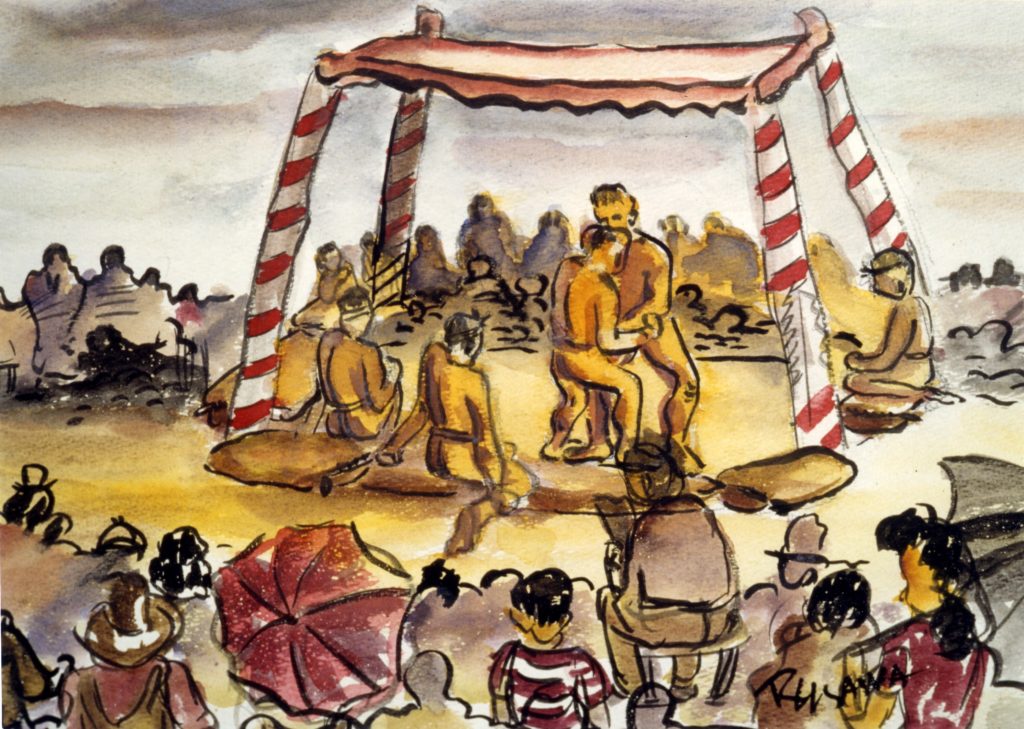

Ruth Asawa, Sumo Wrestlers (1943). © Estate of Ruth Asawa, courtesy of David Zwirner.

Some of the wall texts are very explicit about the reasons the artists were incarcerated. For example, Joe Massey’s explains that he attempted to shoot his first wife, failed, and accidentally killed someone else. Then, after escaping from prison he shot and killed his second wife. Other texts don’t mention the cause of imprisonment at all. How did you decide how to contextualize these parts of the artists’ stories?

We’re often [showing] art-historical figures who are no longer with us, and whose stories are extremely well known, such as Gustave Courbet. He was accused of tearing down the Vendôme Column, which he claimed he didn’t do, but that’s why he went to jail, because he was one of the Communards of 1871. That’s part of his biography. For those artists who are no longer living and for whom the jail time was a part of their biography that has been repeated over and over again, we would include that. And for those artists who are living, we just asked them. And if they wanted us to include their story, we did, and for those who didn’t, we didn’t.

Are there any themes that you see recurring in the works of incarcerated artists?

Yes, certain things that recur are very logical, like drawing as documentation: this is what it looked like in my cell, this is how I lived, this is how I suffered, this is what happened to me. You see a lot of portraiture because if you don’t have a view out your window, you’re going to look at your neighbors or friends or comrades. Richard Dadd’s portrait is actually of his jailer—he looks like a nice fellow. There’s also a kind of drawing that’s used to barter or sell and we don’t have much of that kind of work in the show but there is some, [such as] fantastic works on prison-issue handkerchiefs that come from the American southwest, and envelopes that have been decorated. That’s a kind of drawing you see a lot of. We also have a recurring kind of drawing that’s in the form of greeting cards. In the case of the Soviet Gulag we have three greeting cards, and there’s a great card by a prisoner from Santiago, Chile, sent to his wife.

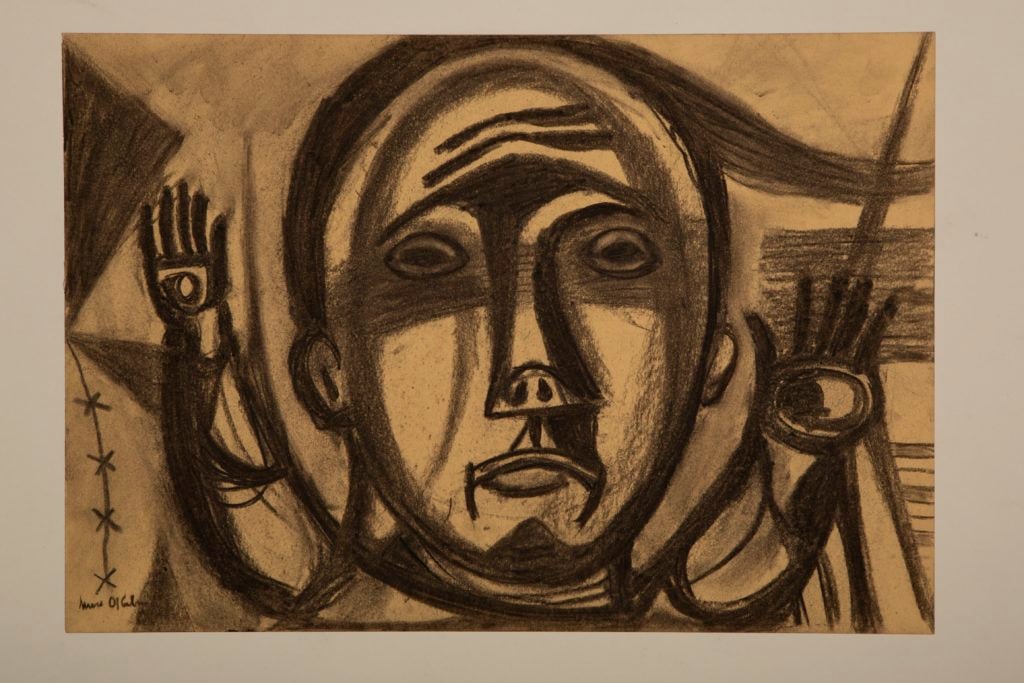

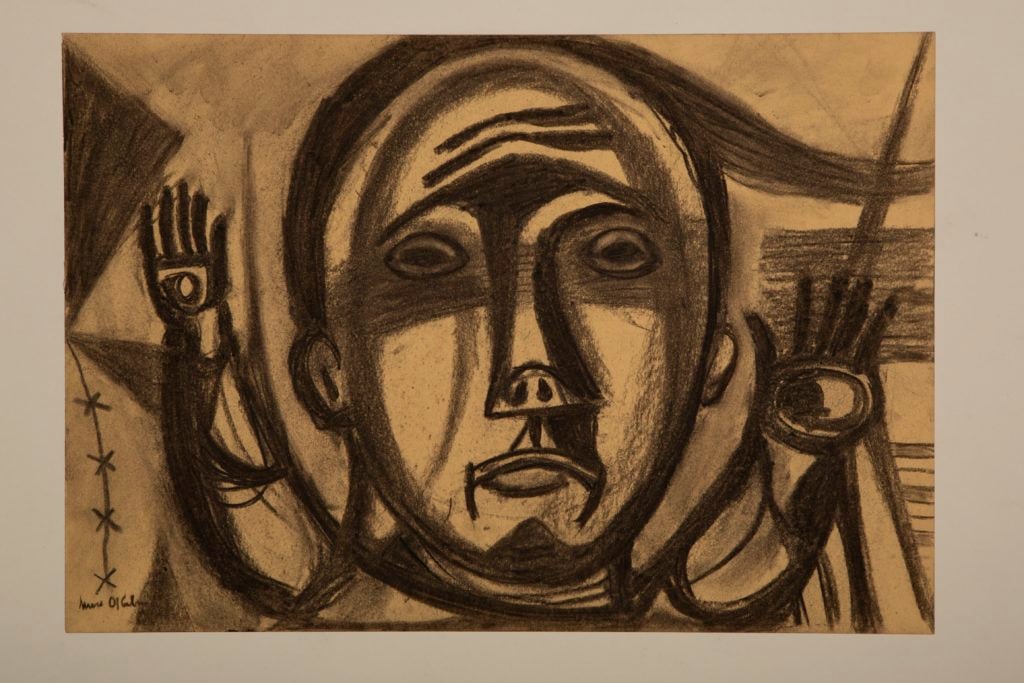

Miné Okubo, Untitled (Single Figure With Arms Raised) (1942–44). Japanese American National Museum.

That leads into this other whole subgenre: epistolatory works. Herman Wallace, one of the Angola Three, who was held in solitary confinement for over 30 years—he was a Black Panther accused of murder—corresponded with an artist called Jackie Sumell and she saved all the letters because he was in his head building his dream house. Another type is works for sale, such as handmade playing cards—like those in the show by Gil Batle, which were made to be played with, or perhaps to be sold or traded. That’s a genre that comes out of at least American prisons. There are also non-narrative expressions. You can see that with Halina Olomucki or Miné Okubo, who was one of the inmates in US Japanese internment camps. These are artists making art that is expressive of their feelings, as opposed to documenting their situation.

Let me ask you something, do you think going through the exhibition is depressing?

No, the circumstances surrounding the art are often very dark, but the works themselves vary so much—you don’t get the sense that every artist was in a constant state of despair.

Yes. It doesn’t crush the human spirit in the end. It’s great if drawing or art is a vehicle for that, for proclaiming your humanity even when people are trying to take it from you.

Do you think that incarceration changed the way any artists worked?

For Gustave Courbet it was the end of his career and it broke him. The same with Jacques-Louis David, because these were patriots, real Frenchmen, and they were both exiled. Courbet died in Switzerland. Certainly you see with David a big change, but of course these are people at the top. Courbet was a Communard, David was the painter to Napoleon, so to see everything in ruin and devastation after all that work is tough.

But there are some artists who found their voice in prison, such as Inez Nathaniel-Walker. Her figures are portraits of people incarcerated with her. She lived out the rest of her life as an artist in the Finger Lakes doing portraits like that. It’s very difficult to tell apart her portraits from when she was incarcerated from those that came after. You can only tell by the kind of paper.

There’s been a lot of interest in art made in confinement recently. Earlier this year the Smithsonian acquired drawings made by migrant children in US custody and at the same time, the Brooklyn Public Library had a show of works made by artists for inmates in solitary confinement. Have you noticed this trend? What do you make of it?

Absolutely, and it’s because mass incarceration has finally come to the fore as one of our major, major societal problems. It’s a horrifying issue but now we have a TV show, Orange Is the New Black, and it’s in the culture, in the discourse. This is not a unique thing. We’re one of a whole number of exhibitions.