On View

Leonardo da Vinci’s Greatest Unfinished Painting Literally Has His Fingerprints All Over It—and Now You Can See Them for Yourself

The work will soon go on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The work will soon go on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Sarah Cascone

The painting is unfinished, its origins shrouded in mystery—and yet it has been hailed as one of the great masterpieces in the history of art. And now, an entire exhibition is dedicated to it at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

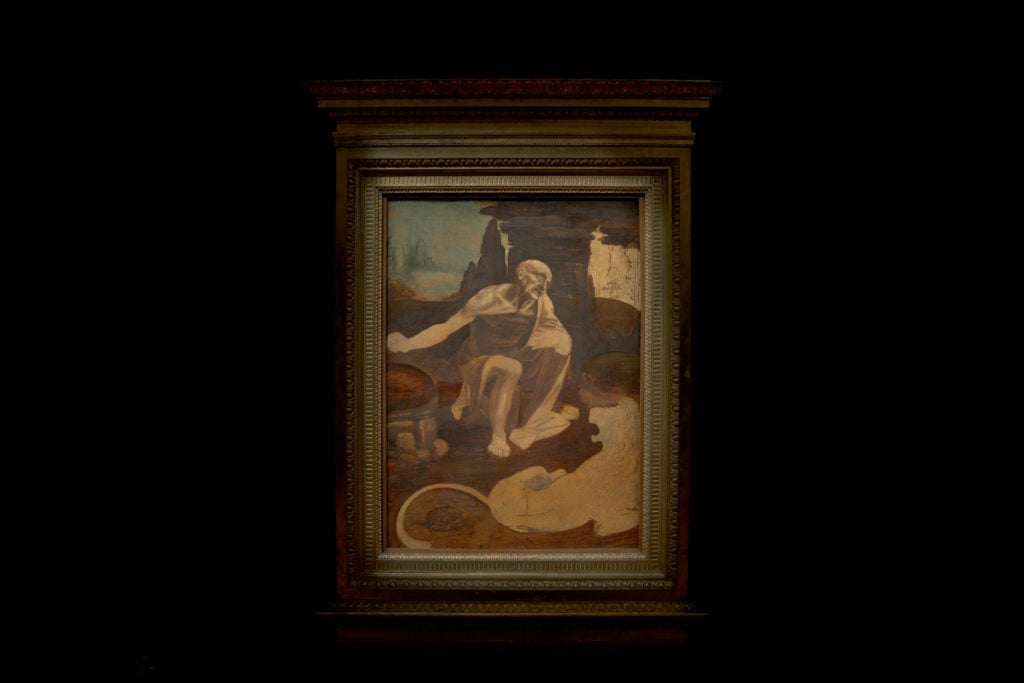

The work is Leonardo da Vinci’s St. Jerome, and it is on loan from the Vatican Museums in Rome (where it is normally on view in the Pinacoteca art gallery) as part of the worldwide celebrations of the 500th anniversary of the artist’s death.

“It’s hard to part with a Leonardo at any moment,” said Met director Max Hollein at the press preview for the show. “It’s especially hard to part with a Leonardo in this very year when the whole world wants to do a Leonardo show and only very few can.” (The two museums have been collaborating on projects, such as last year’s blockbuster exhibition “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination,” for more than three decades.)

“We usually do exhibitions with many, many works, but Leonardo is different and this painting is certainly different,” added Hollein, noting that St. Jerome is “one of possibly only six paintings whose authorship by Leonardo has never been questioned.”

Leonardo da Vinci, St Jerome (begun circa 1482). © Governatorate of the Vatican City State, Vatican Museums. Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The painting shows St. Jerome at prayer at the end of his life, a hermit in the wilderness, alone save for his lion companion—a common Renaissance subject. And yet it stands alone in its deeply moving, intimate depiction of the penitent saint in a moment of private reverie. As Jerome stares up at his crucifix, his spiritual struggle is plain to see, even though many passages of work show little more than the ground preparation on the wood panel, with hastily sketched outlines.

“For Leonardo, a painter’s most ambitious goal was to convey a composition with convincing emotion,” said exhibition curator Carmen Bambach. “Few paintings in the history of Western art can elicit such a powerful psychological reaction.”

Part of the painting’s power comes from the fact that you can literally see Leonardo’s hand in it.

“A close examination of the paint surface reveals the presence of Leonardo’s finger prints in the upper left portions of the composition,” Bambach said. “Leonardo used his finger to distribute the pigments and to create a soft focus effect in the sky and landscape.”

A major Leonardo scholar, Bambach recently published her authoritative, four-volume catalogue raisonné, Leonardo da Vinci Rediscovered—an undertaking 24 years in the making. But at the Met, St. Jerome is being shown in a spare, almost empty gallery to reflect the painting’s solemnity. “The concept was to create a chapel-like sanctuary to heighten the profound contemplative dimension of the painting that Leonardo himself intended,” she said.

Bambach believes that Leonardo intended St. Jerome as an aid for personal prayer and meditation, although there are no known documents detailing the circumstances of its creation. The first mention of the work comes in the will of Swiss artist Angelika Kauffmann (1741–1807). Some years after, it was purportedly rediscovered in Rome by Napoleon’s uncle, Cardinal Joseph Fesch.

Leonardo da Vinci, St Jerome (begun circa 1482) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. © Governatorate of the Vatican City State, Vatican Museums. Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

What’s undeniable is that the saint’s head was cut out to create a more finished-looking painting, and that the cuts and rejoinings are still clearly visible in the panel today. According to some accounts, Fesch found one part of the picture at an antique shop, and the rest at a shoemaker’s.

“Although it seems very mythical,” Bambach said, “there is something in the story that has the ring of truth.”

“Leonardo da Vinci’s St. Jerome” is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Lehman Wing, Gallery 955, 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York, July 15–October 6, 2019.