On View

Long Lost Van Gogh Paintings Go On View in Amsterdam Amid Controversial New Documentary

Convicted burglar offers detailed account of the 2002 theft

Convicted burglar offers detailed account of the 2002 theft

Eileen Kinsella

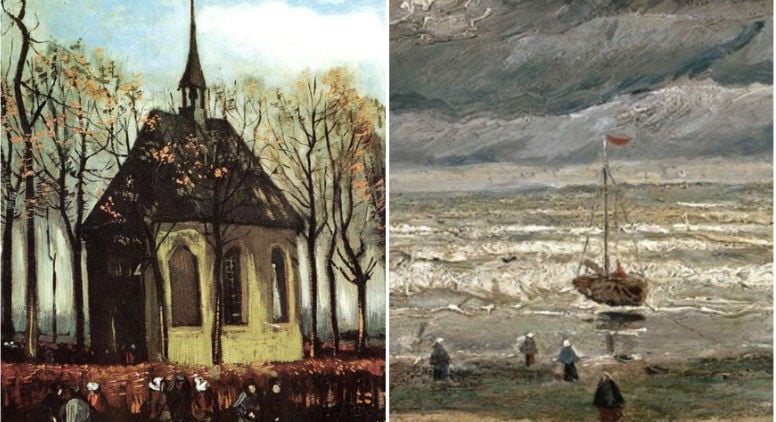

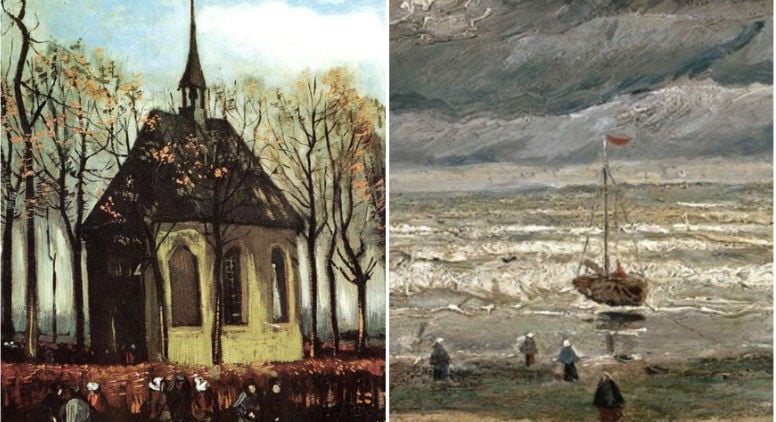

Tomorrow morning in Amsterdam, the Van Gogh Museum is planning a press conference to mark the return and unveiling of two long-lost masterpieces: The Church in Nuenen and The Beach of Scheveningen. The return is a major deal, because the works were brazenly stolen from the museum’s collection in 2002.

The New York Times got a jump on the story today with a lengthy and extremely detailed report regarding a documentary airing on Dutch television tomorrow night (KRO-NCRV) that features an unusual focus–the thief himself, who for the first time in 15 years, has fully admitted his guilt.

Times reporter Nina Siegal spoke to the burglar, a Dutchman named Octave Durham, who, by his own admission, is, or was, a career criminal.

Interestingly, the Van Gogh Museum is still so furious with Durham over his actions and denial of culpability that it refused to cooperate with the documentary and has criticized the focus on Durham. However, museum staff did talk to Siegal, with director Axel Rüger stating, “The museum is the victim in this case, and I would expect very different behavior from someone who shows remorse… He knew exactly what he had done and he never breathed a word. To us it feels as if he is seeking the limelight.”

Filmmaker Vincent Verweij defended his decision to give Durham a platform, even while acknowledging the “tricky ethics” associated with doing so. Further, Verweij says Durham was not compensated for his participation in the film.

“The interesting thing is that you never see documentaries or articles about art theft from the perspective of the thief,” said the documentarian. “It’s always the experts, the museum people, the prosecutors, but never the ones who actually do it, and I think that’s a unique perspective. It’s not meant to be a glorification of this guy.”

Durham comes across as a colorful character. “Some people are born teachers. Some people are born footballers. I’m a born burglar,” he tells the Times.

After Durham and his accomplice, Henk Bieslijn, stole the works, they tried to sell them to a Dutch criminal named Cor van Hout (who was convicted of kidnapping Heineken beer magnate Alfred Heineken in 1983). But there was a dramatic twist in the caper: Van Hout was killed on the same day the transaction was due to go down.

Durham and Bieslijn then sold the paintings to an Italian mafia boss, Raffaele Imperiale, for roughly €350,000 ($380,000), divided the proceeds, and went on an international spending spree.

More than a decade went by with no leads. But last September, Italian authorities found the works at Imperiale’s mother’s home near Naples, wrapped in cloth near the kitchen. Imperiale has since fled to Dubai and may face extradition to Italy, where he has been sentenced to 20 years in jail for multiple offenses, not limited to his connection with the Van Gogh heist.

For Durham’s part, he was released from jail in 2006 and has paid about €60,000 of an imposed €350,000 fine. He was subsequently jailed again after a failed bank robbery, according to the Times. In 2013, he reached out to the Van Gogh Museum and offered his assistance in retrieving the works while still maintaining his innocence.

The museum rejected his suggestion that they buy the works back and declined his offer.

Durham met Verweij in 2015 and told him he wanted to help find the paintings so that he could make amends for his crimes, but inexplicably still maintained his innocence to the filmmaker as well. Verweij says he was skeptical of Durham and told him outright that he didn’t believe he was innocent.

Eventually he agreed to meet Durham at a cafe, “and he admitted that he’d told me a lie and that he did the break-in.” His on-camera confession here confirms long held suspicions, but will have no further legal implications for the serial burglar.