Art & Exhibitions

Is Luciano Benetton the World’s Biggest Little Art Collector?

The collection contains commissions from more than 20,000 artists.

Photo: courtesy Imago Mundi

The collection contains commissions from more than 20,000 artists.

Hili Perlson

Luciano Benetton, who turns 80 this year, was never one to shy away from controversy. In the late ’80s, while most of the world was busy turning away from the AIDS crisis, Benetton, together with iconoclastic photographer Oliviero Toscani, forced people to look death in the eye by advertising his colorful clothing line with scenes of a Christ-like AIDS patient wasting away in a hospital room.

Few if any companies—clothing or otherwise—have combined art, social consciousness, and fashion with quite the same brazenness. While the press and public argued over the company’s motives, Benetton took his oblique approach to corporate identity and applied it to his second greatest passion: art collecting.

But while most collectors equate bigger with better, Benetton’s idiosyncratic collection, which has no commercial aspirations, focuses on unknown and under-represented artists from all four corners of the world, whom he commissions, through a network of local curators, to produce work in the very small format of only 10×12 centimeters.

Wadi Mhiri, Pink Revolution (2013). Tunisian collection.

Photo: Courtesy Imago Mundi

The idea for the collection was born when Benetton met Ecuadorian artist Miguel Betancourt, who gave him a tiny canvas in lieu of a business card. Now, eight years and thousands of artworks later, the Imago Mundi project lives as an online archive, a series of catalogs, and traveling exhibitions that showcase Benetton’s vision of the world as seen through art.

On September 1, the latest exhibition, entitled “Imago Mundi, Map of the New Art,” opened at the Giorgio Cini Foundation in Venice, with a display of nearly 7,000 works by artists from more than 40 countries. The artworks are installed in specially designed compartments, grouped by country and positioned according to continent. There are collections from Germany, Sweden, Greece, Cuba, emerging American artists, the Bushmen of the Kalahari, and Australian Aborigines, among many others.

At first glance, the image of a hall filled with thousands of paintings neatly installed into modular hanging systems seems overwhelming. Indeed, skepticism could be one’s first instinctive approach to Imago Mundi. There’s a whiff of naivety (or is it megalomania?) to the desire to catalog the entire world; to archive a united image of something that is defined by multiplicity.

Lenah Manyoro

I Love My Country (2015). Bushmen from Kalahari collection

Photo: Courtesy Imago Mundi

But delving into the collection’s tiny treasures, it soon becomes clear that the vision for the collection has expanded far beyond its simple beginnings. “It’s not a collection but rather an idea that keeps evolving” Luciano Benetton told artnet News. “Borders become less important, and the focus gradually shifts. The next project is dedicated to amassing works by artists from the 54 ethnical minorities of China,” he added, explaining the broader new approach. Other future plans include a catalog of artists in Kashmir and the Ainu people of northern Japan.

What also becomes immediately apparent is how political strife affects artistic expression. The most recent collection dedicated to Syria shows a multi-media installation sourced by the London-based artist Zaher Omareen, who asked 35 Syrian artists—some based in Syria and some elsewhere, including in refugee camps—to send him unedited one-minute videos free of dialogue. The films are screened on mobile phones, which were neatly placed within the miniature canvases.

Kim Yong Bom Please Fly High (2013). North Korean collection

Photo: Courtesy Imago Mundi

Artists from other countries tackle enduring difficulties. The Tunisian collection looks back at the Arab Spring to question the legacy of the revolution; collections from Iran, Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, and Algeria include mostly women artists and explore representations of the body; works from North Korea show an entirely different approach to expression and authorship, with works created in an artist colony where workers specialize in emulating popular styles, European or local.

Other collections delight in their ingenuity, with the Swedish and German works in particular speaking to the artist’s role in a constantly challenging society.

And while the collection largely features emerging artists, viewers sometimes stumble upon big names such as David Byrne, Laurie Anderson, Christo, Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, Korakrit Arundachai, Sigalit Landau, Menashe Kadishman and many more, all of whom have contributed to the collection for free.

Olaf Nicolai SKINNER (2015). German collection.

Photo: courtesy Imago Mundi

Indeed, many were skeptical at first. Some artists didn’t want to work on such small scale, or even criticized the art-as-donation model. But, as the collection started growing and traveling (a smaller version of the show was presented in Venice in 2013, and other shows were staged in Vienna, Dakar, and Rome) bigger and more established artists wanted to donate their creations too.

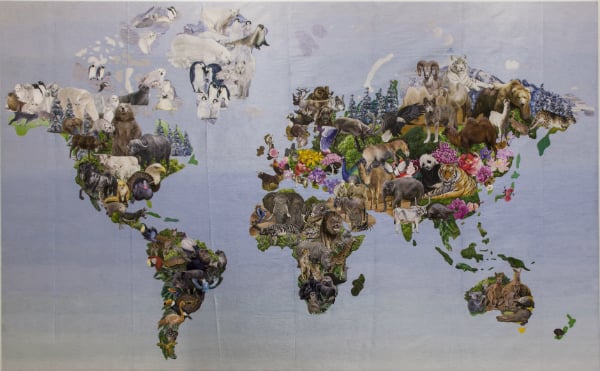

At the end of the hall hangs a huge and marvellous canvas embroidered in North Korea. It’s a map of the world stitched with intricate representations of the continents by the animals that inhabit them. (Perhaps unsurprisingly, Mr. Benetton is an avid collector of maps.) It’s the complete antithesis to the rest of the collection, and seems almost archaic against the wealth of artistic languages contained beneath.

World Map, Artwork created for Imago Mundi by eighty artists from the embroidery department of the Mansudae Art Studio (Pyongyang, North Korea), under the direction of Ji Jong Yol, Jon Yong Bok, Kim Mi Ran.

Photo: Courtesy Imago Mundi

Small as they are, Imago Mundi’s artistic miniatures could attest to the need to create a world which we can understand. For Benetton, an entrepreneur whose success is partially beholden to the needs and desires of the market, these works stand for the ability to stop, decelerate, and peer into a micro-cosmos of self-expression. “But as soon as we’ll be finished with it, there’ll be a new generation of artists and we’ll have to start all over again,” he says with a smile, and I get the feeling that this thought doesn’t bother him at all.

“Imago Mundi, Map of the New Art is on view at Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice from September 1 -November 1, 2015.

Related stories:

artnet News Top 200 Art Collectors Worldwide for 2015, Part One

artnet News Top 200 Art Collectors Worldwide for 2015, Part Two