Art & Exhibitions

Amid Rampant Anti-Semitism, Modigliani’s Jewish Identity Helped Fuel His Artistic Vision

This fall, the Jewish Museum will present a survey of the artist's early works made in Paris at the turn of the 20th century.

This fall, the Jewish Museum will present a survey of the artist's early works made in Paris at the turn of the 20th century.

Henri Neuendorf

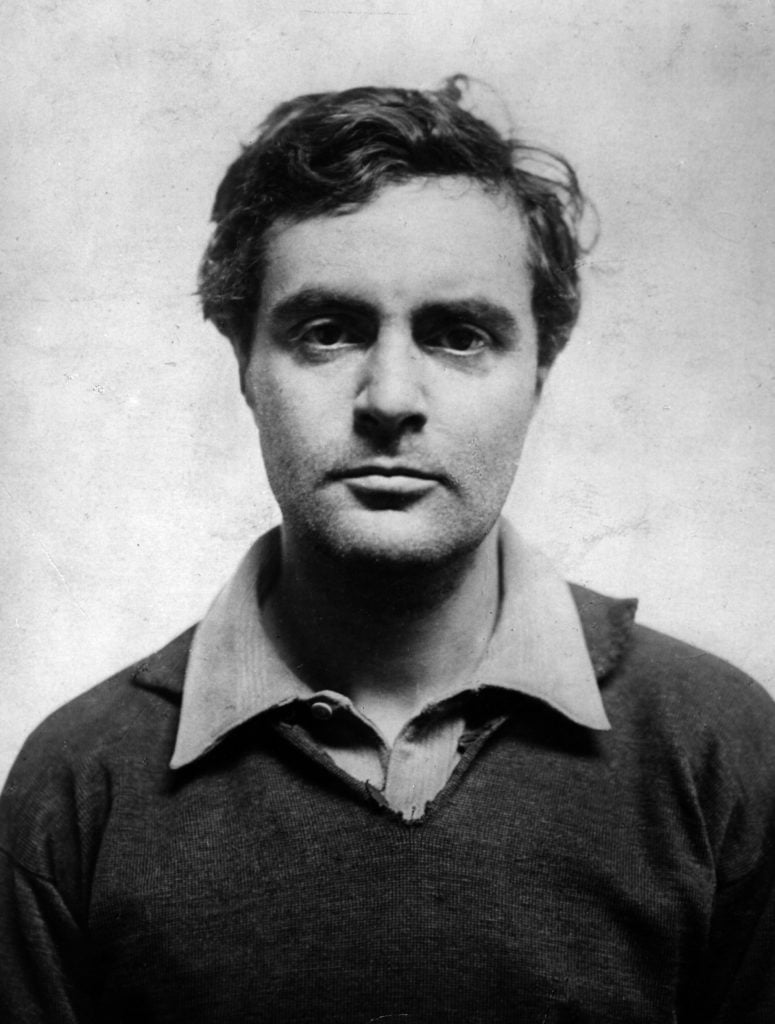

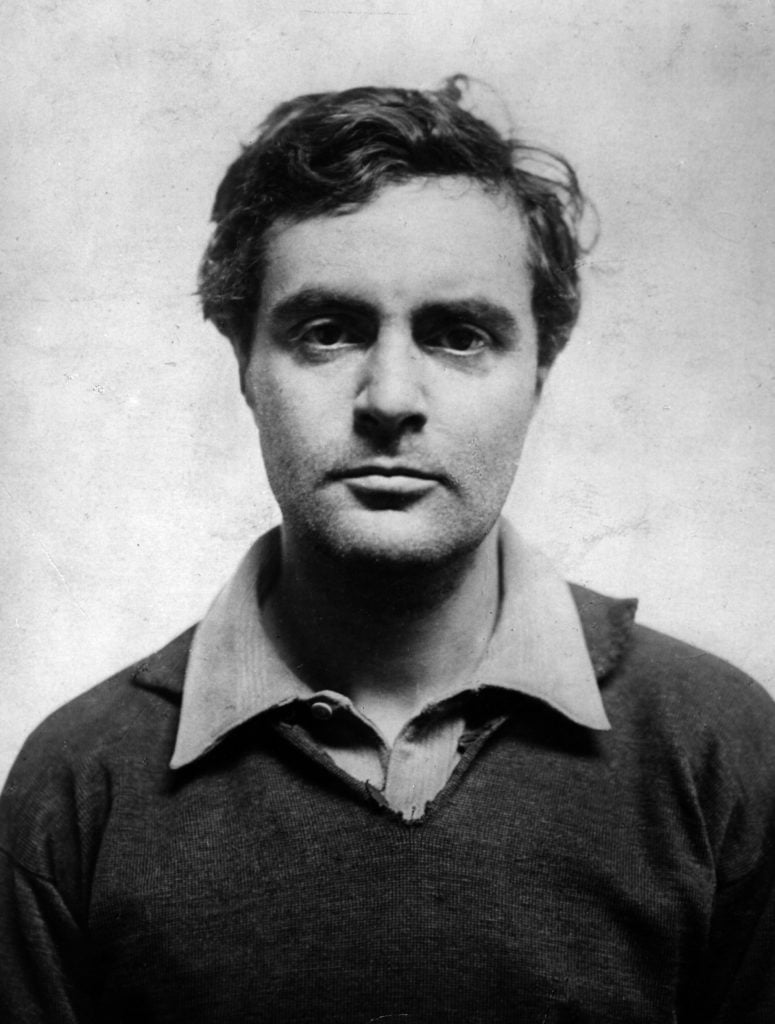

The early phase of the Amadeo Modigliani’s artistic career, which was spent in Paris at the turn of 20th century, will be the focus of a new exhibition at New York’s Jewish Museum in September. “Modigliani Unmasked” will encompass approximately 150 of Modigliani’s early drawings, sculptures, and paintings, alongside a number of multicultural artifacts that influenced the artist’s cultural expression. The show will center on how anti-Semitic sentiments, prevalent in Paris at the time, helped shape the aesthetics of his work during his short, yet extremely prolific 14-year career.

Although Modigliani’s early work is typically viewed as subordinate to his late paintings, understanding the anti-Semitic social and cultural climate in which these early works were created is crucial to apprehending Modigliani’s overall oeuvre, and how it was influenced by his own interpretation of his identity as a Sephardic Jew.

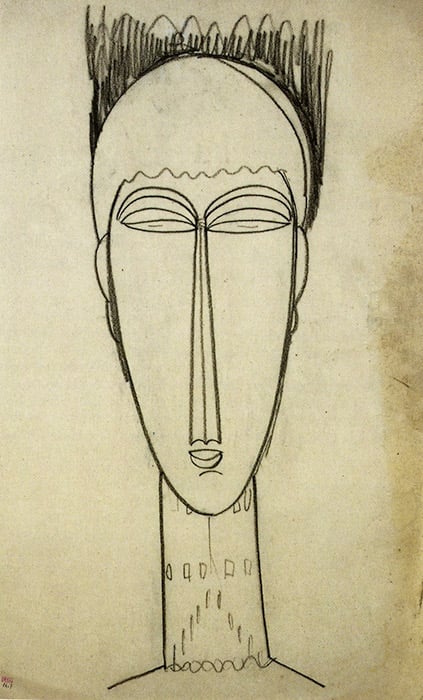

Amedeo Modigliani, Head. (ca. 1911). Photo: Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen.

When he arrived in Paris in 1906, Modigliani for the first time in his life experienced social ostracism and anti-Semitism, propagated by the likes of the racist publisher Edouard Drumont who spread ideas that contrasted sharply with the artist’s more tolerant upbringing in Italy. At the same time, Modigliani was fluent in French thanks to his French mother who grew up in Marseille. This allowed the artist to blend in with the French culture, and move between different social spaces with greater ease than some of his fellow Jewish artists from Eastern Europe.

Amedeo Modigliani Paul Alexandre (ca. 1909). Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates, London, Image provided by Richard Nathanson.

“He understood identity and Jewishness as incredibly fluid and dynamic, and not at all in the sort of racist, fixed way that the French did at the time,” curator Mason Klein told artnet News.

According to Klein, the effects of the racism Modigliani suffered and observed in Paris found their way into his work, particularly his unique physiognomic take on facial features. “I think he was in some way parodying the extreme caricature-ness in which Jews and ethnic types, Africans, etc. were depicted in the popular press,” the curator explained. “He’s very much fixated on Jewish faces—prominent nose, deep-set eyes, large lips. He exoticized or produced that extreme image because he was so different from it in real life.”

Amedeo Modigliani Head of a Woman. (1910-11). Photo: National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Modigliani’s subjugation to xenophobia and anti-Semitism, while fostering his own interpretation of identity and cultural hybridity, increasingly encouraged him to incorporate a host of diverse influences into his work, especially non-western traditions, including ancient art from Greece, Egypt, and Africa. Evidence of African tribal masks, in particular, can be observed in his renderings of exaggerated, elongated faces, which would become a hallmark of his art-making.

“The mask became a great signifier of this veiled, enigmatic quality or notion of identity,” Klein adds—a metaphor for his ability to assimilate in France without truly belonging.

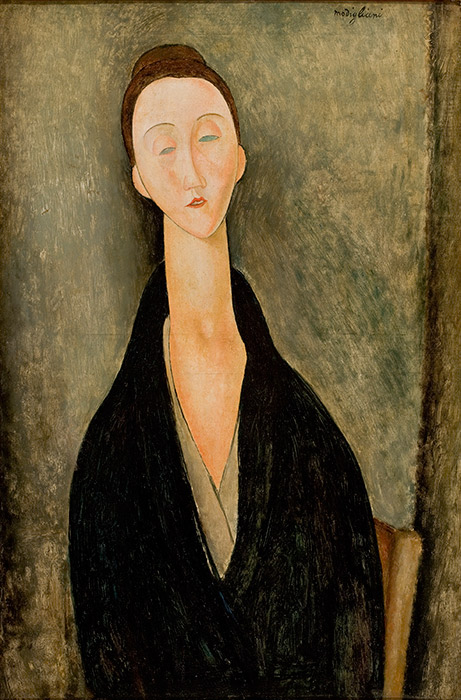

Modigliani’s experiences and early work during his formative years in Paris inspired him to question the status quo of portraiture, and its purpose within the sphere of modern painting. “You see this vacillation between naturalistic and more abstract stylization from painting to painting,” Klein noted. “And that’s informed by his early sculpture and early work that questioned portraiture, [and] questioned the nature of portraiture that was previously based on immutable identity and inevitable truth and profound being—which he rejected.”

Amedeo Modigliani Lunia Czechowska (1919). Photo: João Musa, courtesy of Museu de Arte de São Paulo.

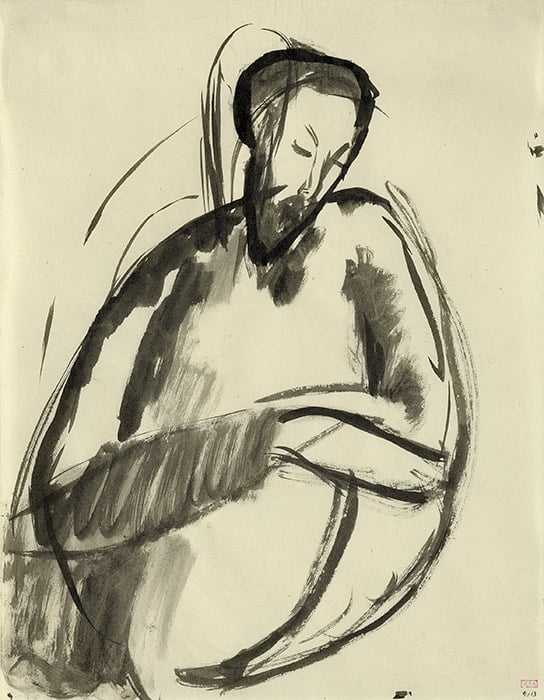

The exhibition will also include life studies of female nudes, an unfinished portrait of Dr. Paul Alexandre—Modigliani’s first great patron and dear friend—and drawings of heads and caryatids, which would later inform his sculptures, a medium he would dedicate himself to in the latter part of his career.

“Modigliani Unmasked” will be on view at the Jewish Museum, New York, September 15, 2017–February 4, 2018.