On View

To Mark 50 Years of Public Art in New York, See the 5 Most Controversial Works to Shock the Big Apple

From Keith Haring to Richard Serra, artists have a long history of upsetting New Yorkers with their public projects.

From Keith Haring to Richard Serra, artists have a long history of upsetting New Yorkers with their public projects.

Sarah Cascone

Fifty years ago it would’ve been hard to imagine a public sculpture in New York that wasn’t a statue of a hero. But as a new show at the Museum of the City of New York, “Art in the Open: Fifty Years of Public Art in New York,” shows, there has been an explosion of public art in the past half-century, led in part by the Parks Department, Creative Time (launched in 1973), Percent for Art (1982), the MTA Arts and Design (1985), and the Public Art Fund (1977).

This year also marks the 50th anniversary of New York City’s first large-scale outdoor public art exhibition, organized by future Public Art Fund founder Doris Freedman in 1967.

“There’s an incredibly rich infrastructure for putting art out in the open here in New York,” museum curator Lilly Tuttle told artnet News during a tour of the exhibition, which takes that 1967 group show, titled “Sculpture in the Environment,” as its starting point.

The historic exhibition featured work by artists including Louise Nevelson, Barnett Newman, and Claes Oldenburg—who, in a piece that would never be permitted today, hired gravediggers to excavate a six-foot-wide hole in Central Park. (Even at the time, “it caused quite an uproar,” Freedman’s daughter and current Public Art Fund president Susan K. Freedman told artnet News. “No one got that it was art.”)

One sculpture from the exhibition, Tony Rosenthal’s The Alamo, became a beloved permanent installation, today more commonly known as the Astor Place Cube.

“A model of public art that put the artists’ voice and cutting edge art comes into play in the 1960s,” Tuttle said. “What we’ve seen over this 50-year period is artists using traditional media like sculpture and murals, but also water and land, and doing art in the air, and making art out of garbage, and doing art that is performative with people. The scope of public art has just grown and grown.”

Works by Kara Walker and Agnes Denes on view in “Art in the Open” at the Museum of the City of New York. Photo courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

Even though public art is often ephemeral, and can be massive in scale, making it impossible to display in a museum context, the show is a visually compelling combination of photographs, preparatory models and sketches, video footage, and other documents.

The show does include some original work, however. There’s Rob Pruitt’s The Andy Monument, a 2011 Public Art Fund project that served in part as an impromptu memorial to Warhol, as well as one of the polyester resin sugar-coated children from Kara Walker’s 2014 Creative Time blockbuster, A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby. Of less-recent vintage is a portion of another Creative Time project, the Wall Street newsstand from Red Grooms’s 1975 Ruckus Manhattan, a massive sculptural recreation of the New York streetscape.

Red Grooms, part of Ruckus Manhattan (1975) installed in “Art in the Open” at the Museum of the City of New York. Photo courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

One theme that runs throughout the show—and the history of public art—is controversy. Many of the works have become flash points of community disagreement—indeed not even those historical hero monuments can escape criticism today.

“Controversy is not in and of itself a bad thing,” said Tuttle, noting that artists are looking to start a dialogue with viewers, and don’t necessarily want to create work that is too safe or easily accepted.

In some instances, the show displays the letters of rejection and outrage from politicians and community members that have embroiled various works of art. Here are five of the most controversial public works that appear in “Art in the Open.”

1. Ai Weiwei, Good Fences Make Good Neighbors (2017)

When the dissident Chinese artist Ai Weiwei was tapped to create an ambitious citywide public art installation in New York, no one was surprised that he might use it to take an overtly political stance. But it wasn’t the project’s pro-immigrant message that had the public up in arms.

Instead, the city’s most recent public art controversy came about because the four-month long exhibition, titled Good Fences Make Good Neighbors, was set to displace the Christmas tree in Washington Square Park, traditionally given pride of place under the triumphal arch.

Village denizens were angry that they had not been consulted first about how the work would affect their holiday celebrations. The tree, which will be lit December 6, is now on display between the arch and the fountain, according to the Washington Square Park Blog.

Though Public Art Fund places great importance on working with communities to ensure works are well-received, Freedman admitted that “people upset about displacing a Christmas tree, that’s not something I’m sympathetic to.”

Christo and Jeanne-Claude The Gates, Central Park, New York City (2005).

Photo by Wolfgang Volz, courtesy of the artists.

2. Christo and Jeanne Claude, The Gates (2005)

“A lot of people don’t know that this was actually 26 years in the making,” said Tuttle of The Gates, which were originally proposed in 1979.

Though the project was ultimately a massive success, bringing an influx of tourists to the park during the traditionally slow month of February, the city initially denied the artist duo the necessary permits. On view at the Museum of the City of New York is a copy of the Parks Department report assessing the project’s potential impact, as well as letters from citizens and the Audubon Society praising the 1981 decision to prevent the installation. (“Christo has a record for persistence, and no doubt he will be applying again,” notes the society’s prescient missive.)

“The park was in a very broken down, deteriorated state,” said Tuttle. “There was a feeling that what the park really needed was rehabilitation.”

Fast forward to 2005, and the support of Mayor Michael Bloomberg, and the story has a completely different ending. “It really lifted the city’s spirits, and it also kicked off a period in the early 21st century of fearless, bold, large-scale public art in the city,” said Tuttle, who puts Olafur Eliasson’s New York City Waterfalls and Tatzu Nishi’s Discovering Columbus on that list.

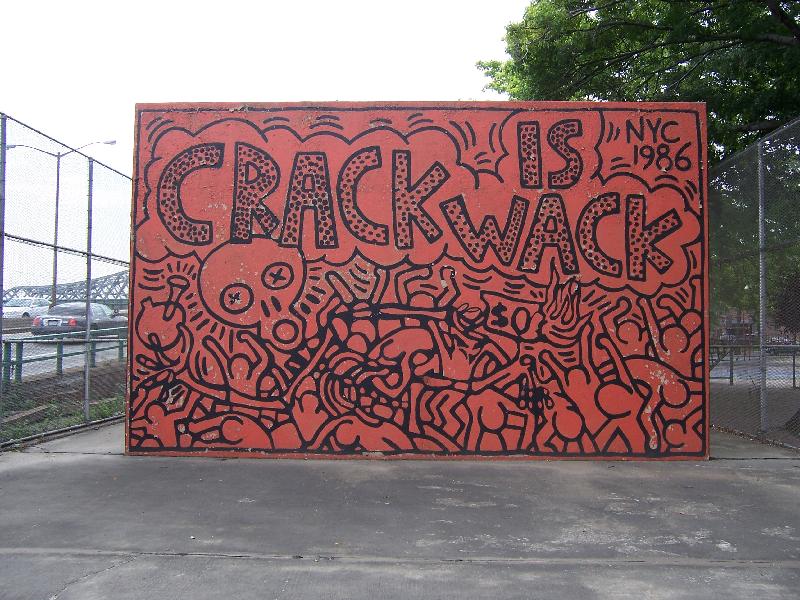

Keith Haring, Crack Is Wack (1986). Photo courtesy of the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

3. Keith Haring, Crack Is Wack (1986)

Visible while driving south on the Harlem River Drive, Keith Haring’s Crack Is Wack mural was originally created without permission, leading to the artist’s arrest and the work’s destruction.

“It was controversial because it was unauthorized,” said Tuttle. “On the one hand it’s graffiti at a time when Mayor Ed Koch was really cracking down on graffiti. On the other hand it’s an anti-drug message during the era of Nancy Reagan and ‘just say no.’ The artist put the city in an awkward spot.”

It was also an important moment for Haring, whose career was just taking off. For a 1982 CBS news report, which is on view in the exhibition, reporter Charles Osgood follows Haring through the subway as the artist creates chalk drawings on blank advertising panels.

But while Haring was being hassled by the police underground, he was also selling similar work for thousands of dollars in art galleries. “He had this outlaw persona, but at the same time he was really gathering a following and becoming a darling of the downtown art scene,” said Tuttle.

In the end, Haring only paid a $100 fine for the Crack Is Wack mural. He later received an apology from the Parks Department, and was asked to recreate the piece as a permanent installation.

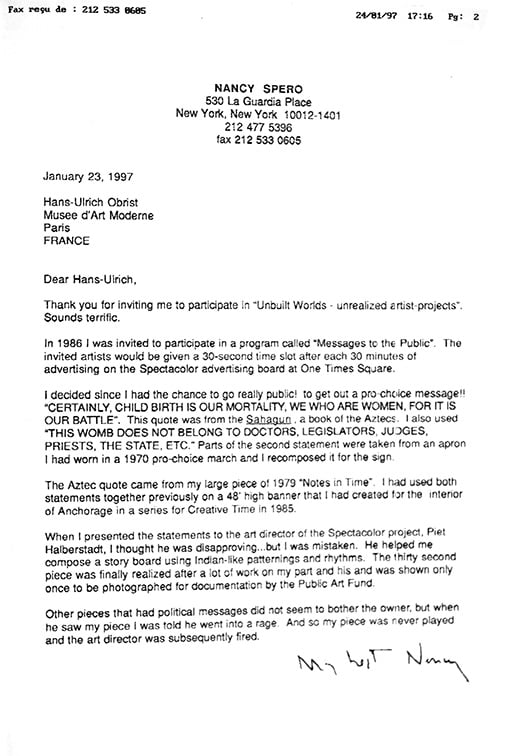

Nancy Spero wrote this letter to Hans-Ulrich Obrist about her cancelled Public Art Fund “Messages to the Public” piece. Courtesy of the artist.

4. Nancy Spero, “Messages to the Public” (1982)

One of the longest-running public art exhibitions was the Public Art Fund’s “Messages to the Public” series, which presented works on the massive Spectacolor light board in Times Square each month between 1982 and 1990. One piece, however, was not allowed to run, and appeared on the billboard only once, for documentation purposes.

Nancy Spero had wanted to send a pro-choice message, so she designed animations that read “Certainly, child birth is our mortality, we who are women, for it is our battle” and “This Womb Does Not Belong to Doctors, Legislators, Judges, Priests, the State.”

“It turned out my boss was an ardent Catholic and he vetoed it,” artist Jane Dickson, who worked as an animator for the Spectacolor light board and approached the Public Art Fund about the collaboration, told artnet News. In addition to having to ax Spero’s piece, Dickson was forced to include a pro-life work in the first year. “We said, ‘let’s do the 10 artists we want, and then this really crappy fetus piece!'”

“When [the owner] saw my piece, I was told he went into a rage,” wrote Spero in a letter to Hans Ulrich Obrist about an exhibition of unrealized artist projects. “And so my piece was never played and the art director was subsequently fired.”

5. Richard Serra, Tilted Arc (1981)

In 1979, a panel from the US General Services Administration’s art-in-architecture program awarded Richard Serra a commission to create a permanent public artwork for Federal Plaza. Two years later, he unveiled a 120-foot long, 12-foot-high wall of rusty COR-TEN steel, bisecting the plaza. It was met with immediate disapproval.

Following the initial outcry, a public hearing was held and, in 1985, a jury voted to take down the work. Perhaps the most infamous sculpture on this list, Tilted Arc was called “one of the most bitterly contested of all 20th-century sculptures and a watershed work of public art” by the New York Times, following its removal.

“Tilted Arc is obviously the ur work,” said Tuttle. “There was a before and after of how artists looked at the sites, the way they looked at the public-ness of their work.”

“Art in the Open: Fifty Years of Public Art in New York” is on view at the Museum of the City of New York, 1220 Fifth Avenue at 103rd Street, November 10–December 31, 2017.

The panel discussion “Love It or Hate It: Public Art and Controversy” will take place at 6:30 p.m. on Thursday, November 30. Tickets are $20.