On View

A Pop-Up Museum in New York Illustrates the Harmful Effects of Broken Windows Policing

The exhibition aims to highlight the impact of the policy on African American and Latino communities.

The exhibition aims to highlight the impact of the policy on African American and Latino communities.

Sarah Cascone

When the New York Civil Liberties Union puts together a pop-up museum, it’s not your typical Instagram bait. The Museum of Broken Windows, which opened last Saturday, trades colorful photo ops for sobering educational displays that illustrate the harmful effects that so-called broken windows policing has had on the African American and Latino communities, particularly here in New York.

“This is New York City. We should be the leaders in criminal justice reform, and that starts with ending broken windows policing,” exhibition curator Daveen Trentman told artnet News at the museum’s press preview. Her company, the Soze Agency, which specializes in creating social impact campaigns, worked with the NYCLU to organize the organization’s first-ever themed art show. (The NYCLU previously hosted a fundraising exhibition in the wake of 9/11.)

The exhibition brings together work by the likes of Dread Scott, Hank Willis Thomas, Molly Crabapple, and Sam Durant, paired with archival photographs and newspaper articles that present a 50-year history of how the criminological theory—which targets non-violent crime in the hopes of deterring more serious offenses—has worked in practice.

“In fact, reality did not bear out the claims of this being effective policing. Broken Windows destabilized the black community” said NYCLU executive director Donna Lieberman to artnet News, calling out the policy of “stop and frisk,” which ostensibly aimed to get guns off the street, as a big part of the problem. “Ninety percent of stops didn’t result in a summons, let along an arrest. The people who are being targeted are [usually] innocent.”

Michael D’Antuono, The Talk. Courtesy of the artist.

The very real dangers that broken windows policing presents to people of color come to the fore in Michael D’Antuono’s The Talk. The painting, which Trentman called “one of the most evocative and profound pieces that we have here,” shows an African American mother and father warning their young son how to behave when he encounters the police. The TV screen just behind them shows a news story about a similar looking boy who was shot by a white officer. The ticker at the bottom of the screen reads: “No Indictment in Police Shooting of Unarmed Youth.”

Nearby hangs Nafis M. White’s photography series “Phantom Negro Weapons,” each image depicting an item carried by an unarmed African American person who was shot and killed. A pack of Skittles is easily identifiable as the item carried by Trayvon Martin, but most of the photos are blank pages, representing those who were killed despite not holding anything that could be mistaken for a gun.

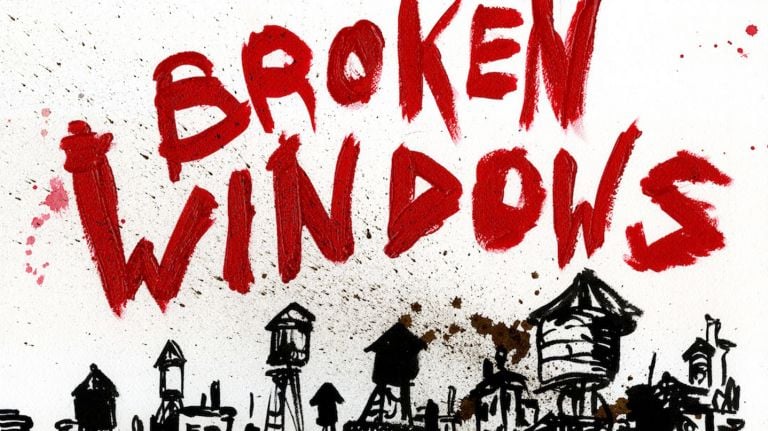

Other tributes to the African American victims of police violence come from Ann Lewis and Tracy Hetzel. For her sculptural installation …and counting, Lewis wrote out 1,093 toe tags to document every police-related death in the US in 2016, from the ones that made headlines to the many whose violent ends went unnoticed by the country at large. The wall text for the piece, being shown in its entirety for the first time, notes that the daily average dropped from 3.2 deaths a day to 2.7 after Colin Kaepernick began taking a knee in protest at NFL games.

In a new series commissioned by the NYCLU, Hetzel has created watercolor paintings of mothers holding up pictures of their sons, each killed by the police. Her subjects include the mothers of Eric Garner and Amadou Diallo, as well as less familiar names. Many of these grieving mothers have banded together, in what Trentman described as “a sorority that nobody wants to be in,” to speak out for reform. Their efforts successfully called on New York Governor Andrew Cuomo to sign an executive order appointing special prosecutors to investigate the deaths of unarmed civilians at the hands of the police.

Tracy Hetzel created this series of watercolors of women holding portraits of their sons who were killed by the NYPD for the Museum of Broken Windows. Photo courtesy of the NYCLU.

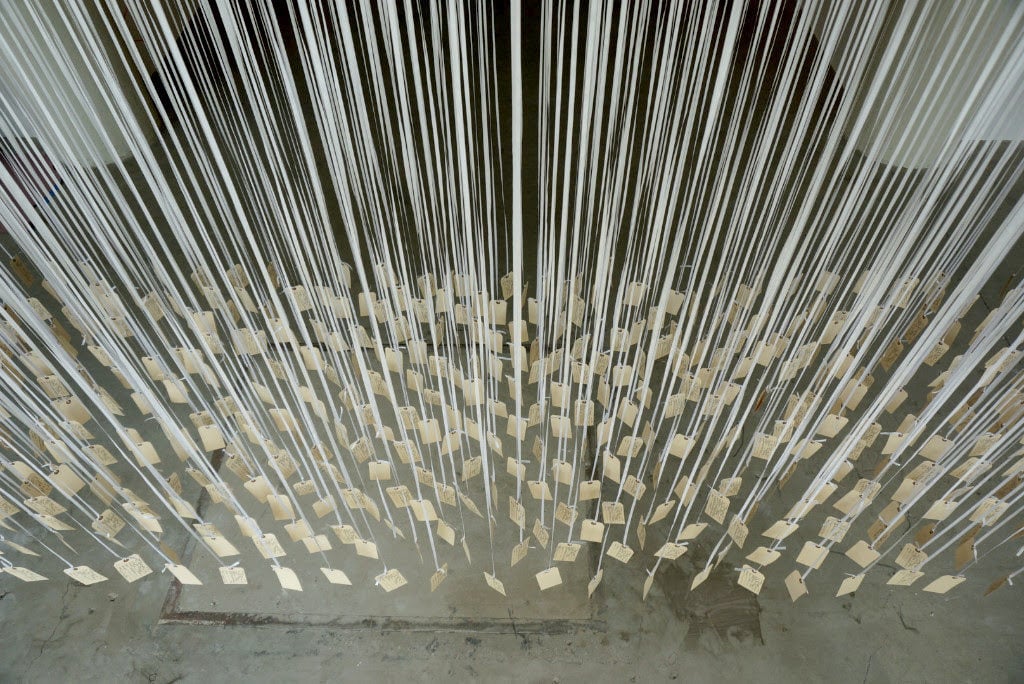

Two of the artists in the show, Jesse Krimes and Russell Craig, are formerly incarcerated, both for non-violent drug offenses. Krimes presents two contraband works made while he was behind bars and smuggled out to his girlfriend. In the works, the artist uses hair gel and plastic spoon to transfer newsprint images from the New York Times to prison bedsheets. Craig turned his court papers into a self-portrait, defying the criminal justice system’s attempt to define him. He also created a collage inspired by the special NYPD unit dedicated to investigating hip-hop stars, such a P Diddy. The unit was founded in 1999 following the deaths of Tupac and Biggie Smalls.

The museum is free and open to the public. At its entrance, visitors are greeted with a parked police car with broken windows and leafy green plants growing out of the roof where the sirens would have been. The piece, by Jordan Weber, is meant to “ignite our imaginations about what it means to feel safe in our neighborhoods,” Trentman said.

On the other half of the storefront, Scott’s flag A Man Was Lynched by the Police Yesterday hangs in the front window. Scott also contributed a series of “Wanted” posters, with police-style sketches of suspects accused of such vague offenses as “furtive movement.”

The exhibition is being called a museum not to capitalize on the current pop-up craze, said Trentman, but because “when you think of a museum, you think of historical artifacts.” The show, she explained, aims to illustrate the role broken windows policing has played in enabling the “tragically seamless transition from slavery to mass incarceration,” and the urgent need to end the still-ongoing practice.

“The key to achieving reform is getting people to understand what the harm is,” Lieberman said. “We hope this art exhibition will help do it.”

See more photos from the museum below.

Ann Lewis, …and counting (2016). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Ann Lewis, …and counting (2016). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Russell Craig, who served time in prison for a non-violent drug offense, made this self-portrait on top of his court document. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Nafis M. White, photograph of Skittles representing Trayvon Martin, from the series “Phantom Negro Weapons.” Photo courtesy of the artist.

Jordan Weber’s police car sculpture at the Museum of Broken Windows. Photo courtesy of the NYCLU.

The NYCLU’s Museum of Broken Windows is located at 9 West 8th Street and is open 10 a.m.–8 p.m. Sunday–Thursday, and 10 a.m.–8 p.m. Friday and Saturday, September 22–30, 2018.