Art & Exhibitions

Paul Allen’s Traveling Show of Landscape Paintings Is a Plutocrat’s Plaything

They are second-rate paintings by first-rate masters.

They are second-rate paintings by first-rate masters.

Christian Viveros-Fauné

Ever wondered what today’s masters of the universe really crave when they let themselves go, art-wise? One answer comes courtesy of Paul G. Allen, co-founder of Microsoft and the 45th richest man in the world, according to Forbes. Allen recently unveiled part of his multimillion dollar art holdings in a show of landscape paintings at Washington DC’s Phillips Collection.

After walking through the milquetoast display, it’s hard not to consider a mogul-worthy T-shirt. Here’s my pick: “I spent the yearly budget of several megamuseums, and all I got were these lousy trophies!”

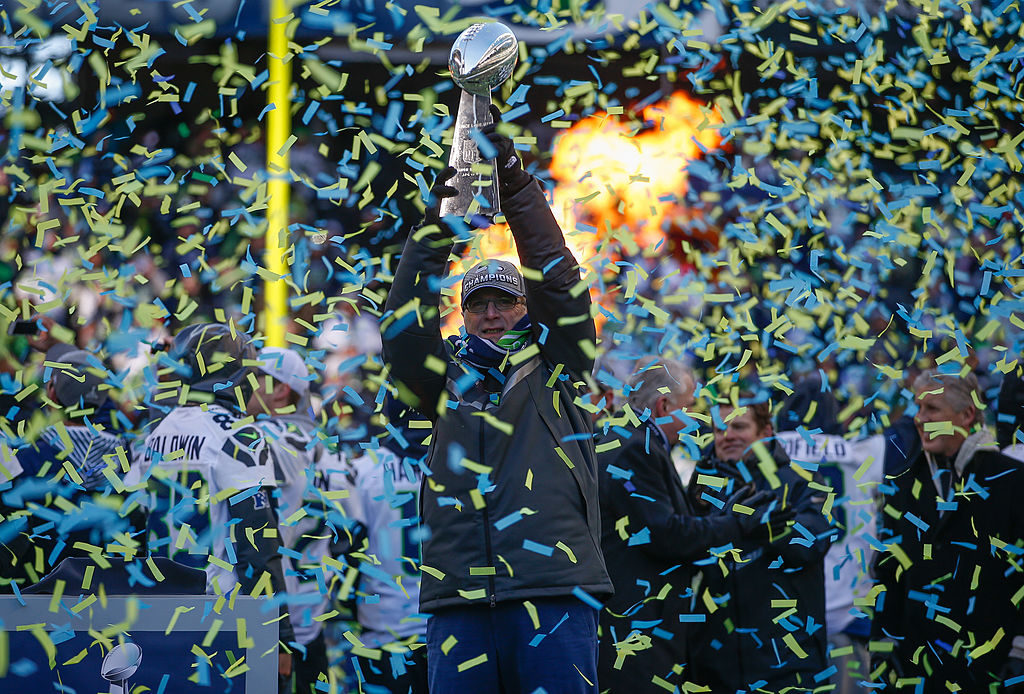

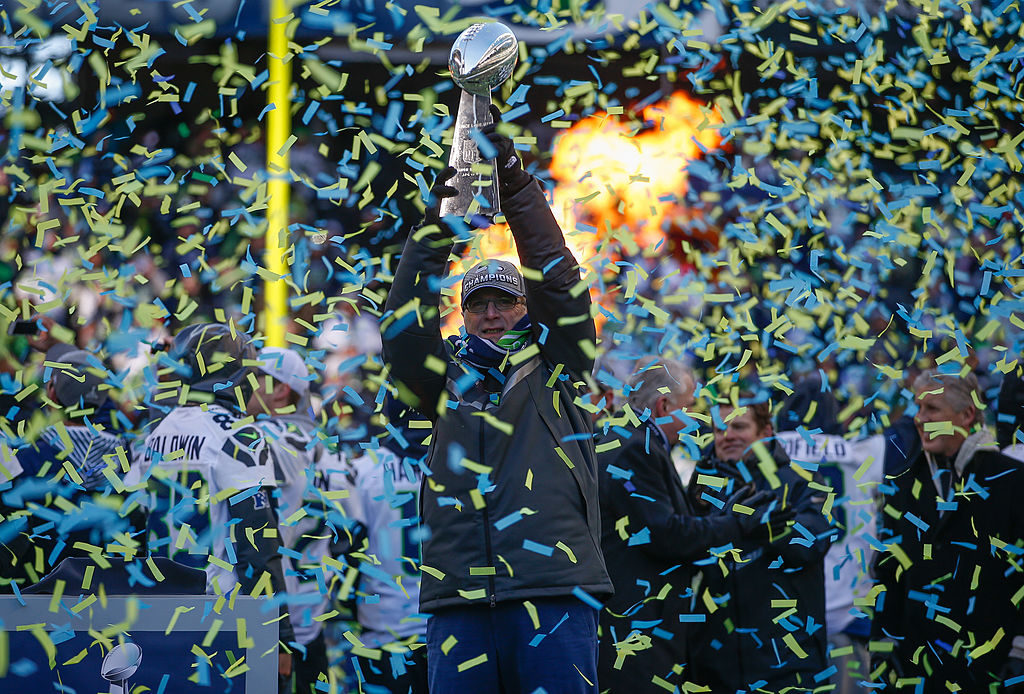

Self-evidently titled “Seeing Nature: Landscape Masterworks from the Paul G. Allen Family Collection,” the exhibition bundles together some 39 pricey paintings, spanning five centuries, from the hush-hush, mega-private collection of the very public owner of the Seattle Seahawks, the Portland Trail Blazers, and Vulcan Aerospace, among other flashy entities.

Jan Brueghel the Younger, The Five Senses: Sight (c. 1625).

Image: Paul G. Allen Family Collection.

Co-organized by the Portland Art Museum, the Seattle Art Museum and the Paul G. Allen Collection, the show—which originated in Portland last October—is presently in the middle of a five-city US tour. After DC it travels to the Minneapolis Institute of Art and the New Orleans Museum of Art, before heading back to the Seattle Art Museum. Unsurprisingly, the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation is a major donor to the two museums organizing the exhibition, and Vulcan Inc, Allen’s philanthropic venture, “provided generous in-kind support.”

Is there irony in the fact that Allen—one of the men most responsible for the world being seen today through high-tech, glossy screens—loves handmade pictures of well-ordered nature? You bet your sweet Microsoft stock there is! But this is not Allen’s only arty venture by a long shot. In addition to “Seeing Nature,” the mogul has also bankrolled the year-old Seattle Art Fair, along with Pivot Art + Culture, a 3,000-square-foot Seattle gallery located inside the Allen Institute for Brain Science.

Pivot Art + Culture opened with a much-hyped show that featured loans of paintings by Chuck Close, Lucian Freud, Willem de Kooning, and others. And while there is currently an exhibition on view, titled Imagined Futures: Science Fiction, Art, and Artifacts from the Paul G. Allen Family Collection (through July 10, 2016), there has been speculation that Pivot might be closing. In a 2015 article in the Stranger, Jen Graves points to the magnate’s legendary flakiness. Frank Gehry—who designed Allen’s gleaming Experience Music Project, which is home to his rock and roll memorabilia and Lord of the Rings manuscript—described Allen as “a client who dictated from above, but hardly seemed to be paying attention.” Another close Allen-observer in Graves’ article pegged the $18 billion man as having “entrepreneurial ADD.”

Giovanni Antonio Canal, known as Canaletto, The Grand Canal, Venice, Looking Southeast from San Stae to the Fabbriche Nuove di Rialto (c. 1738).

Image: Courtesy of Paul G. Allen Family Collection.

“Seeing Nature” represents the first solid glimpse the world has seen of Allen’s art-related venture philanthropy. A highly imperfect show, it provides clues to Allen’s secretive collecting while tracing a recognizable footprint for his forthcoming exhibition activities. Allen, it bears mentioning, is a pioneer of high-tech philanthropy in the Pacific Northwest—his art acquisitions, which Forbes valued at $750 million in 2009, hold great sway over regional and tech-industry art stewardship, and will likely do so for years. If “Seeing Nature” is a sign of the times for art collecting, the future looks bleak, indeed.

The first thing one should say about “Seeing Nature” is that it is a checklist show. Few surprises animate what are, mostly, minor landscapes made by major painters. There are, amid some superstars and many understudies, two Canalettos (check), a Turner (check), five Monets (check), a Manet (check), a Cezanne (check), an O’Keeffe (check), a Hopper (check), a Ruscha (check) and two Richters (check). Had Allen wanted to squeeze Rubens and Renoir into his kitchen-sink-landscape conceit, the show would be lousy with them. As it is, the exhibition resembles a Kardashian shopping spree. It’s like Allen simply flipped through Janson’s History of Art, exclaiming, “I’ll have that, that, that and that!”

Gustav Klimt, Birch Forest (1903).

Image: Courtesy Paul G. Allen Family Collection.

Like many bad shows with overblown ambitions, it’s the exceptions to this stunningly middlebrow display that confirm the predictable rule. Even princely pictures take on the characteristics of stable boys when made to pull the cart of their master’s vacuous ideas. Here’s one from Allen’s catalog interview that is repeated like a mantra in the exhibition literature: “There’s something about landscapes that seems almost universally attractive.” Laboring unfairly under the weight of such boilerplate, Cezanne’s rugged view of Mont Sainte-Victoire looks merely forlorn, Klimt’s depiction of a birch forest goes from precise to postcard wan, and the pretty pointillist Paul Signac study of the Brittany Coast resembles a scientific illustration.

And so it goes with “Seeing Nature,” a display of art that is less a curated museum exhibition than the whim of a plutocrat. Allen has all the money in the world, so he can afford to play around with other people’s hard-won ideas—in this case, those of history’s best-known artists. But he should be told, in no uncertain terms, that important museums—even the willing ones—are not his playgrounds, and second-rate paintings by first-rate masters are not his playthings.