Why have there been no great women Pre-Raphaelites? Well, it turns out there were quite a few.

The first exhibition to focus on the women behind the movement that took Victorian Britain by storm reveals that the self-proclaimed “brotherhood” was, in fact, also a “sisterhood” of remarkable female models, writers, and artists who played a crucial role in its success.

“An art movement is a collective,” says Jan Marsh, the guest curator of “Pre-Raphaelite Sisters,”which opens at London’s National Portrait Gallery this week. The show presents a revisionist, feminist history of the group that could not be more timely. “The models, artists, and what we would call back-room girls—the office and studio managers—and wives were all part of the creative process.”

The exhibition is a double first. “The National Portrait Gallery has never done a Pre-Raphaelite show before,” Marsh points out, and she was as surprised as anyone. The movement’s male artists and leading lights—John Ruskin, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Morris—are stalwarts of the Tate’s and Royal Academy of Arts’s exhibition programs.

When asked to propose an idea for the show, Marsh, who is an expert on the Pre-Raphaelites, suggested putting its female members in the foreground. “There was a lot hiding in plain sight,” she says, adding that she is excited by how much of the artists’ work has only recently emerged from obscurity.

Joanna Wells, Study of Fanny Eaton (1861). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund.

The exhibition is the latest to reframe the mainly male art-historical canon by acknowledging the role of not only artists, but female models. Until the 1990s, Fanny Eaton was largely overlooked by art historians even though she was a favorite of several artists. Born in Jamaica, probably of mixed heritage, Eaton’s striking features and dark skin appear in several works by Victorian artists, including Pre-Raphaelite heavy hitters John Everett Millais and Ford Madox Brown.

Eaton also sat for the leading female Pre-Raphaelite painter Joanna Boyce Wells, whose promising career was cut short at age 29. The artist, who had made her successful exhibition debut at the Royal Academy in her early 20s, died during her third pregnancy. “There was no limit to what this wonderfully gifted woman would not have reached in her art,” wrote William Rossetti, the art critic who was the brother of Dante Gabriel Rosetti. A study for a portrait of Eaton by Wells is one of the stars of the show.

Elizabeth “Lizzie” Siddal is a Pre-Raphaelite model who many people will recognize. Marsh has pulled off a coup in borrowing from a private collector a rarely seen autograph copy of story of Siddal as Ophelia in Millais’s great canvas. The full-scale version is a star painting at Tate Britain. As well as a muse to Millais and Rossetti, Siddal was a poet and painter in her own right.

Of all the women in the show, the works of Siddal and another “aspiring artist,” Georgiana Burne-Jones, stand out, Marsh says. Siddal, who eventually married Rossetti, died at 32, her health ruined by an addiction to opium, and suffering from depression. Georgiana Burne-Jones, wife of Edward, was tiny is stature but made of stern stuff.

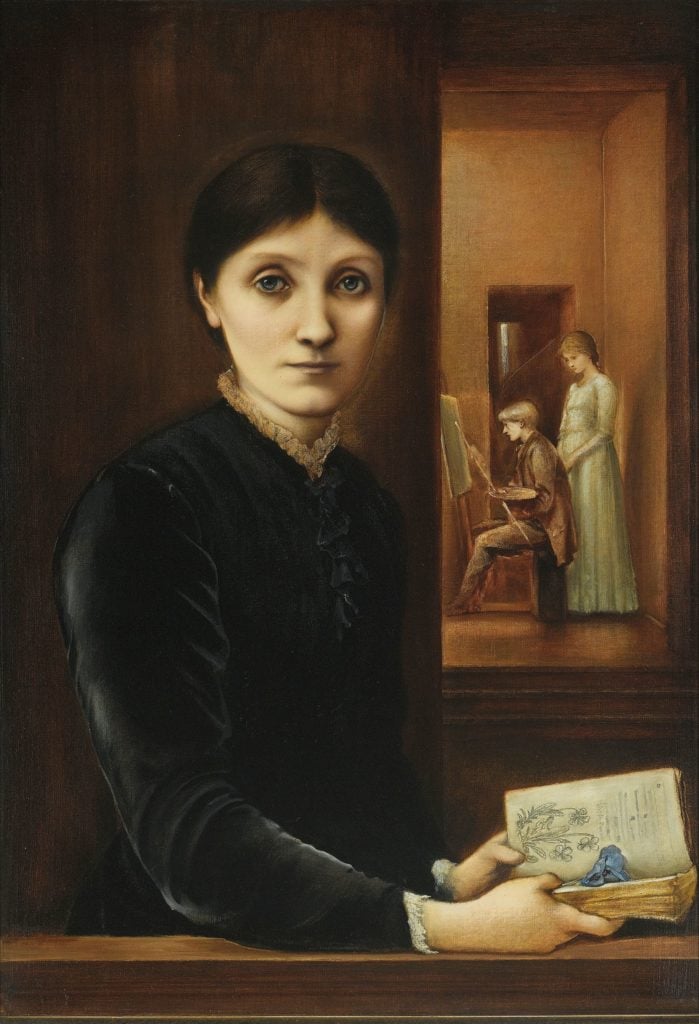

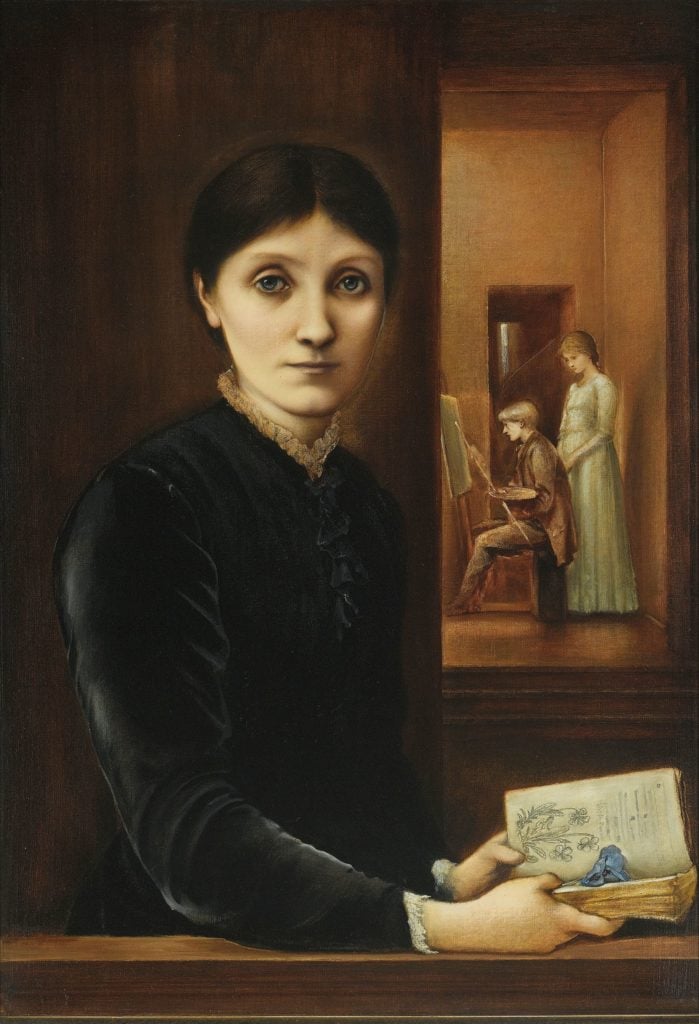

Edward Burne-Jones’s portrait of Georgiana Burne-Jones with her children Philip and Margaret (1883). Private collection, Image courtesy of Sotheby’s, London.

“Georgie was a very determined little woman, and in some ways very unhappy because of the way Ned behaved,” Marsh says. “I hope I have foregrounded her own attempts at art at the beginning of her life” by showing works that have never been displayed in public before. These include ink drawings and verses that she made before she married. She also made fine woodcuts. “There was a book of fairy stories that she and Lizzie Siddal proposed to publish,” Marsh adds.

Burne-Jones had to all but give up art when her husband shut her out of the studio after the birth of their first child. “It was a tragedy,” Marsh says. “She recorded in her biography of her husband, which is also a wonderful autobiography, how she sat in the other room weeping silently.” To add insult to injury, when Edward Burne-Jones was unfaithful with the artist-model Maria Zambaco, she was allowed into his studio while his wife was not.

Georgiana Burne-Jones was what would today be called an activist-artist. A confidant of William Morris, they were kindred spirits who stoically endured problem marriages. “She became close to Morris as he moved into politics,” Marsh says. They both believed in art for all, uniting the arts-and-crafts movement with an idiosyncratic version of socialism. She was instrumental in the founding of the South London Gallery in Camberwell, then as now a largely working-class district.

She became one Victorian Britain’s first female politicians, standing as a parish councilor in her village, which she set about reforming with zeal. Her most courageous act of political protest took place in the village of Rottingdean near Brighton on the South Coast of England. At the height of the Boer War, she stitched an anti-war banner and hung it from the family home. It declared: “We have killed and also take possession.” It caused such outrage that her nephew, the pro-war Rudyard Kipling, had to rush to save Georgiana from being mobbed. Sadly that piece of textile art has not survived.

Annie Miller is the model in Il Dolce far Niente by William Holman Hunt, 1866. Private collection, care of Grant Ford Ltd.

“I would like to re-write the whole narrative of the Pre-Raphaelite women being exploited and hard done by,” Marsh says. “They were active agents in forging their own futures. They seized the opportunities, especially the models,” she says. Women like Annie Miller escaped their social class and probable fate of domestic service, she points out. Siddall was destined to be a seamstress.

“If you think of celebrity models today, someone like Kate Moss, she wants to be an active part of the creative process.” The male Pre-Raphaelites’ muses, or “stunners” as male members called them, were neither victims nor clothes horses. “They were cast in roles and made the most of them,” Marsh says.

“Pre-Raphaelite Sisters,” October 17 through January 26, 2020, National Portrait Gallery, London.