One of the most critically acclaimed exhibitions of 2017, “Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985” from Los Angeles’s Hammer Museum, opened last week at the Brooklyn Museum. It’s the same groundbreaking reappraisal of the work of Latin American, Chicana, and Latina female artists, but the Brooklyn edition has received an injection of New York flavor, thanks to the addition of some new works.

The exhibition, which was originally part of the Los Angeles-centric initiative “Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA,” is the brainchild of Hammer guest curators Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and Andrea Giunta. The two worked closely with the Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art senior and assistant curators, Catherine J. Morris and Carmen Hermo, on the show’s new presentation.

“Radical Women” is the result of nearly eight years of painstaking academic research, digging up little-known and forgotten figures from countries across Latin America. “It’s very important to give voice to a culture that has been erased,” Giunta told artnet News.

In writing these untold stories, Giunta and Fajardo-Hill took a feminist approach, although they acknowledge that the feminist movement was much less prominent in Latin America than in the US. “Women had to be part of the revolutionary movement to change society as a whole, and not be working particularly for the rights of women,” Guinta explained. “But even if they were not proposing their work as feminist art, they were a part of a broader feminist cultural moment.”

Long before the exhibition became a critical darling at the Hammer, the Brooklyn Museum had its eye on what they knew would be an important moment for both Latin American and women’s art.

Installation view, “Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985,” Brooklyn Museum. Photo by Jonathan Dorado, courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

“I actually saw the proposal for this exhibition in 2010, when Cecilia was developing it potentially for the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach, where she was then curator,” Morris told artnet News. “At the time, it was even more ambitious than it is now. It had 20 or 30 more years of history. When I heard it was going to be part of PST, I was very vocal that we wanted to take the show. I feel lucky because I suspect any number of institutions in the city would have taken it if we weren’t already at the front of the line.”

“It’s kind of an intimidating show in some ways because there’s so many artists that most of us don’t know,” she added. “But that’s exactly the value of the exhibition—rather than being about the 120 people you’ve already heard of, it really is a completely new history.”

Perhaps the most important challenge to mounting the East Coast show was staying faithful to the original conceit. “We were thinking primarily about how to maintain the vision of the original curators who devoted so much time unearthing and contextualizing and presenting this work,” Morris said.

Installation view, “Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985,” Brooklyn Museum. Photo by Jonathan Dorado, courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

“‘Radical Women’ was not recontextualized for a New York audience,” Guinta was quick to emphasize. On the other hand, she admitted that differences in the physical layout of the two museums did necessitate some changes. “It is good for us as curators to rediscover the work in a new exhibition space. When you see things in a new order, new connections illuminate, in some ways, pieces that we know very well after eight years.”

“It was amazing how our reconfiguration of the themes brought up completely new questions, new contexts and relationships between the works,” Hermo agreed. “Even folks who saw the show in LA are going to discover new aspects to it.”

Beyond the layout, the exhibition will also showcase three new artists and a new body of work from a fourth, which the Brooklyn Museum hopes will have added appeal for New Yorkers. “Bringing an exhibition that’s so locally specific to LA—we knew right away that we needed to think about New York communities and the way they were represented so that we could tell some of the stories that are specific to diaspora communities here,” Morris said.

Morris and Hermo spoke to artnet News about what to expect in terms of new work in the Brooklyn Museum’s version of “Radical Women.” Below, see the artists that are adding a new dimension to the New York exhibition.

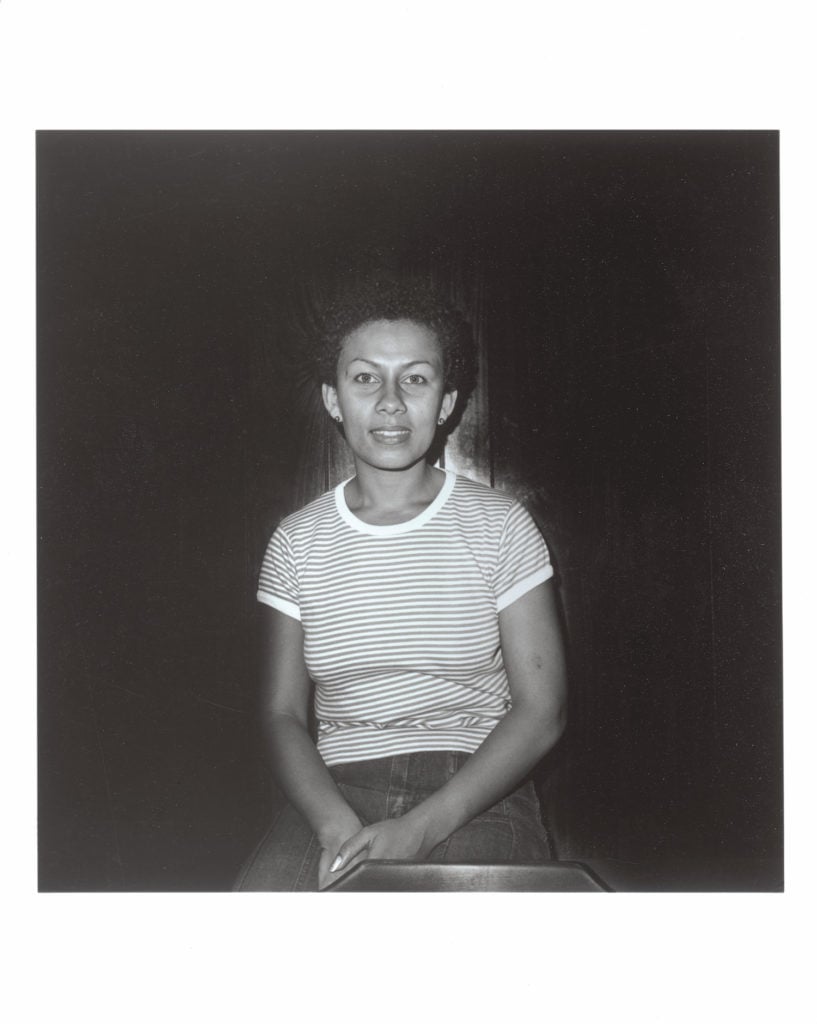

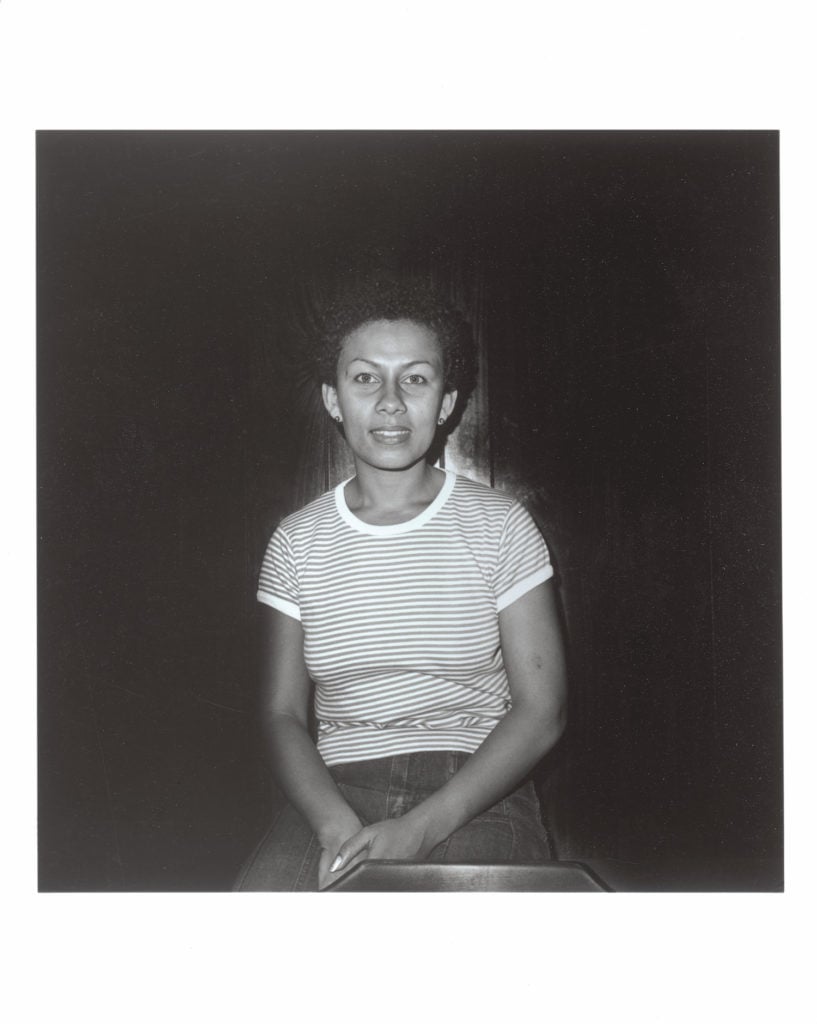

Sophie Rivera (US, born 1938)

Sophie Rivera, Untitled from “Nuyorican Portraits,” (1978). Courtesy of the artist, collection of Martin Hurwitz.

At the Hammer, Sophie Rivera was represented with a bold photograph of a bloody tampon, floating unapologetically in a toilet bowl. At the Brooklyn Museum, that work is joined by a series of photographs, “Nuyorican Portraits” (1978), on loan from the New York-based artist and her husband. Rivera made the series in her hometown in the 1970s, sitting outside on the stoop and asking passersby if they were Puerto Rican.

“If they said yes, she would invite them in for a portrait session,” Hermo said. “They are some of the largest photographs in the exhibition, at a beautiful monumental scale.” The images and their anonymous subjects, she added, became “a way to directly combat negative stereotypes the artist was seeing and experiencing against Puerto Ricans in New York City.”

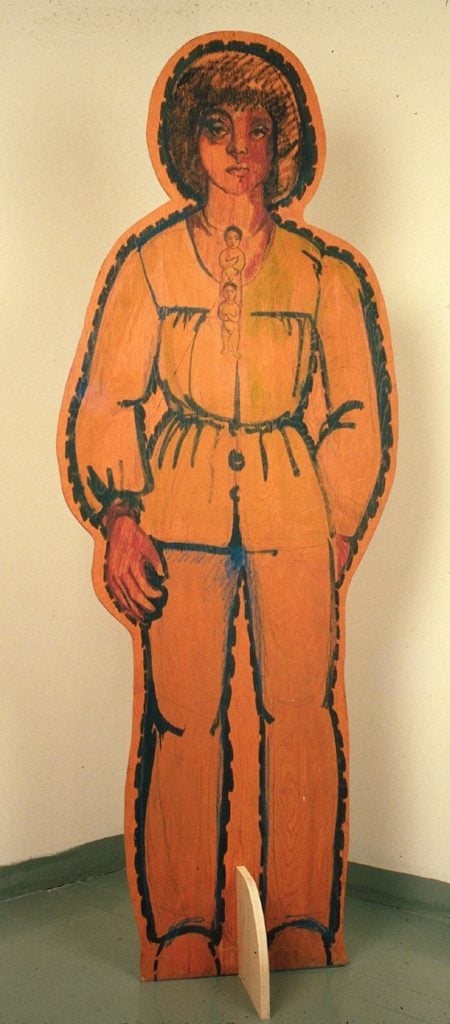

Marta Moreno Vega (US, born 1942)

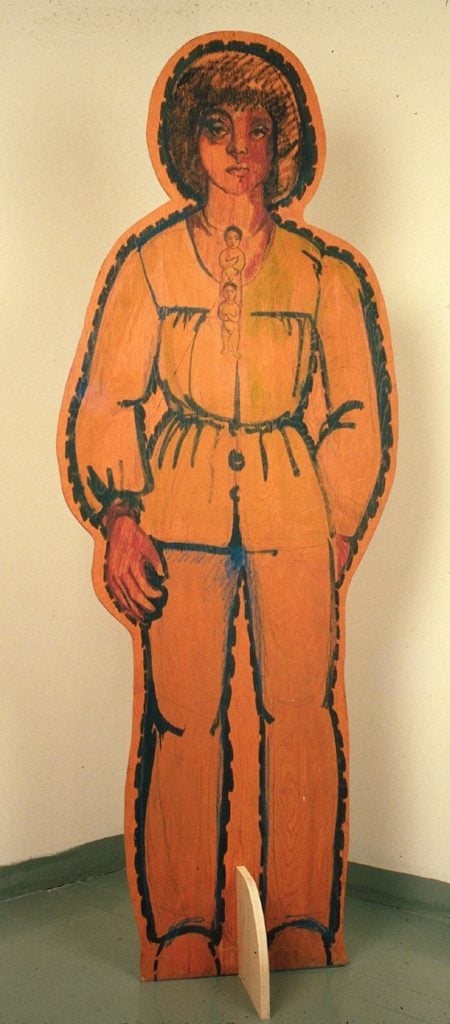

Marta Moreno Vega, Autorretrato (Self-Portrait). Courtesy of El Museo del Barrio.

A self-portrait sculpture, Autorretrato (Self-Portrait) (1973), by Marta Moreno Vega has been added to the opening section of the exhibition, which is dedicated to self-portraits. “It’s this fabulous paper doll come to life—she’s kind of staring down everyone else in the gallery,” Hermo said, describing the piece, which is on loan from New York’s El Museo del Barrio.

El Museo was created by local parents, educators, artists, and community activists looking to rectify the lack of representation of Puerto Rican culture in New York City schools. An instrumental figure the in the founding of the museum, Vega went on to serve as the institution’s second director and to found the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute, also in New York.

The current exhibition coincides with the re-release of Vega’s memoir, which she will promote with a reading and signing during the museum’s May First Saturday programming.

Sara Gomez (Cuba, 1942–74)

On several Sundays during the show’s run, the forum adjacent to the exhibition will feature screenings of long, durational films by artists including Afro-Cuban filmmaker Sara Gómez. “We’ve set up afternoons where one can sit and watch it all,” Hermo said.

De Cierta Manera (1977)—or One Way or Another in English—is a narrative film inspired by the urban growth and revitalization effort in impoverished communities after the Cuban revolution. “She’s focusing on the rebuilding of community housing, and also looking at how women were leading the literacy efforts in Cuba,” Hermo said. “It’s unpacking shifting gender norms in a time of great social change.”

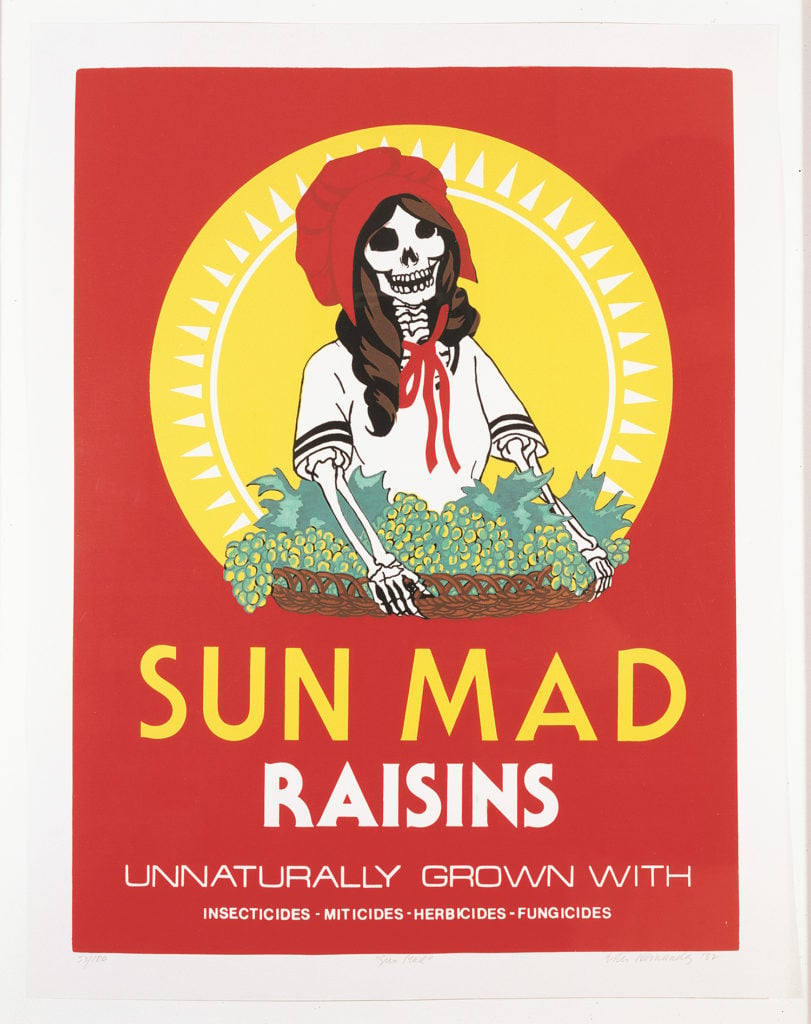

Ester Hernández (US, born 1944)

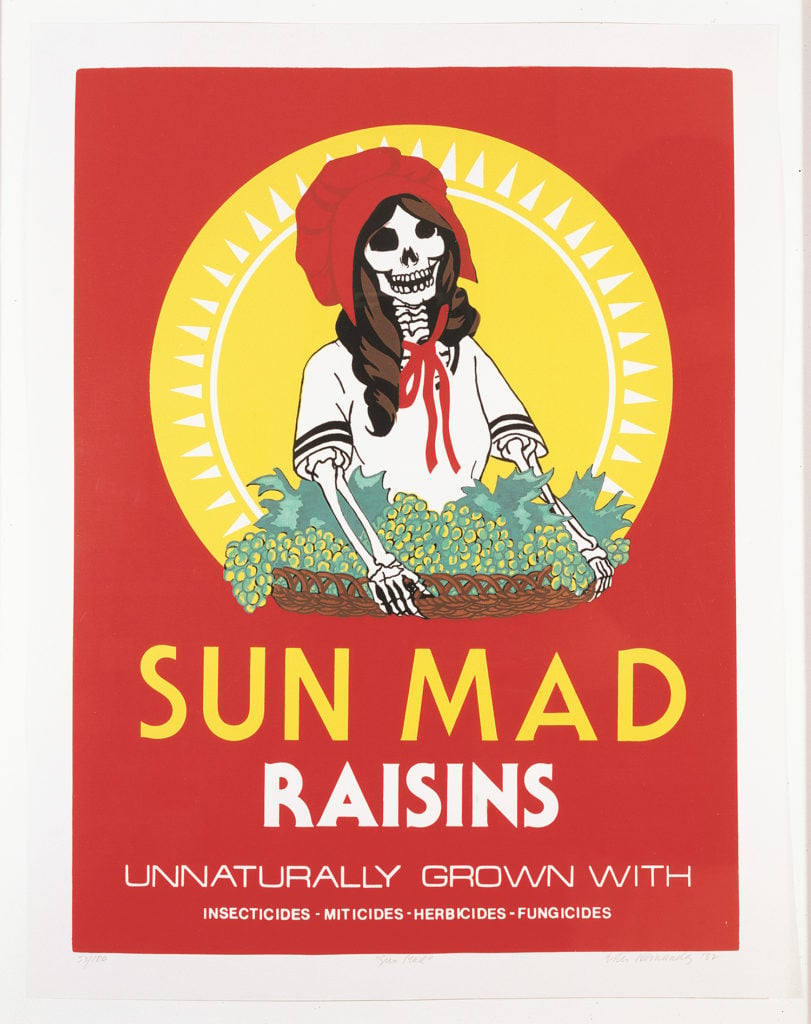

Ester Hernandez, Sun Mad (1982). Collection of El Museo del Barrio, New York. Museum Purchase with funds from the Mexican-American Cultural Foundation. Artwork ©Ester Hernández. Photo by Jason Mandella, ©El Museo del Barrio, New York.

“Ester Hernandez appeared in a lot of the other Pacific Standard Time shows, but was not in ‘Radical Women,'” Hermo said. “We thought of her as an iconic figure working in an activist mode, thinking about feminism, Mexicans based in the US, and issues of pollution, representation, and organizing.”

Her piece Sun Mad (1982) is already a hit on social media among museum visitors. “It’s an acerbic take on the Sun-Maid Raisin box, only with a skeleton women, reading ‘Unnaturally Grown,'” Hermo explained. “It’s a commentary on the pesticides the artist and her family were ingesting while working as farm workers.”

“It really resonates with people,” Morris added. “There’s a clear connection to Pop art and a prescient use of appropriation techniques. It makes me think of Betye Saar’s The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, the appropriation of benign female forms that get used in merchandising.”

“Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985” is on view at the Brooklyn Museum, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art and Morris A. and Meyer Schapiro Wing, 4th Floor, 200 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, April 13–July 22, 2018.