Art & Exhibitions

The Renaissance’s Love Affair With the Nude Gets a Provocative Show at the Getty. See the Highlights Here

'The Renaissance Nude' explores the development of a genre.

'The Renaissance Nude' explores the development of a genre.

Henri Neuendorf

In Europe, the Renaissance was fueled by newly rediscovered classical sculpture, taking inspiration from the naturalism of antiquity. It also made the scientific study of anatomy a central part of painting for the first time. Both of these strands came together in one theme in particular—the nude—and an important new show at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, “The Renaissance Nude,” gives the subject the serious treatment it deserves.

With over 100 masterpieces from Italy, France, Germany, and the Netherlands made between the early 15th century to the early 16th century, the Getty show offers a comprehensive survey of one of the central preoccupations in European art. And while painting and sculpture take center stage, the show also includes drawings, manuscripts, and prints, showing how the study of the human form manifested in different realms.

“We felt that in telling the story of the nude, something transformational had to be done through really major examples,” curator Thomas Kren told artnet News in a call. “It’s not like we wanted to do a masterpieces show—we didn’t. But to show the range of achievement for this subject, we had to keep the standard high.”

Jean Fouquet Virgin and Child (ca. 1452–1455). Photo: Courtesy of Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen. Image © www.lukasweb.be–Art in Flanders vzw, photo Dominique Provost.

The highlights are many. They include a Jean Fouquet painting of the virgin and child (ca. 1450), on loan from Antwerp’s Royal Museum of Fine Arts; Antonio da Correggio’s Danaë, (1531) on loan from Rome’s Borghese gallery; and Antonello da Messina’s depiction of St. Sebastian (1476–1477).

The curatorial team tried to cast their net as wide as possible to show the range and evolution of the genre, Kren explained.

“The goal was to try to show the ways in which there were these formal or thematic links. In fact, a lot was shared despite regional and stylistic differences, so in a way we were more focused on the thematic,” he said. “But we also had a built-in limitation: We were trying to find subjects that were represented across Europe.”

Antonello da Messina Saint Sebastian (1478–1479). Photo: Photo Credit: bpk Bildagentur / Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister/Elke. Estel/Hans-Peter Klut/Art Resource.

Thus, for example, “The Renaissance Nude” contains a number of different examples of the St. Sebastian theme, including works by Messina, Moderno, and Hans Holbein the Elder. As the patron saint of the Plague-stricken, St. Sebastian saw a spike in popularity as as the deadly illness spread around the continent.

Titian, Venus Rising from the Sea (Venus Anadyomene) (ca. 1520). Photo: courtesy of National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Similarly, depictions of Venus were found all around Europe in the 1520s. Artworks featuring the Greek goddess of love include paintings by Jan Gossart (ca. 1521) and Titian (ca. 1520), whose sumptuous Venus Rising from the Sea is a highlight of the show.

“We were looking for subjects that were ultimately pan-European,” Kren summarized.

See other examples of artworks featured in “The Renaissance Nude,” below.

Michele Giambono, The Man of Sorrows (ca. 1430). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Konrad von Vechta, Saint Barbara’s Escape from her Father (top); Torture of Saint Barbara by Knife and Scourge (bottom) (ca. 1430–35). National Museum of Finland

Photo: The Picture Collections / The Finnish Heritage Agency. Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

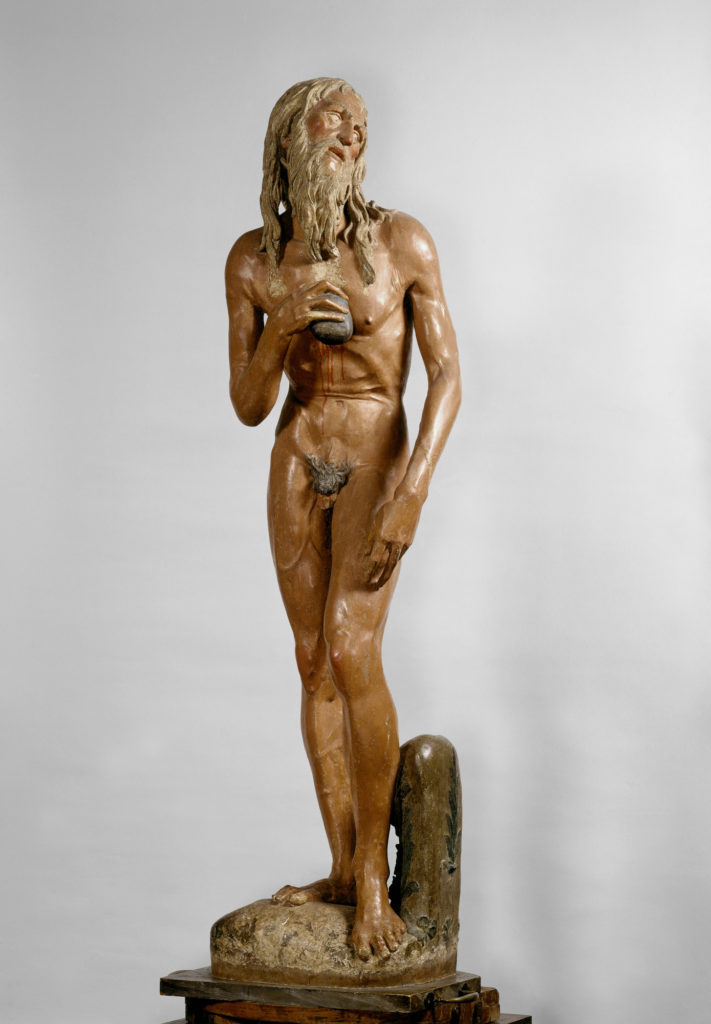

Donatello, St. Jerome (1460s). Image: Scala/Art Resource, NY. Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

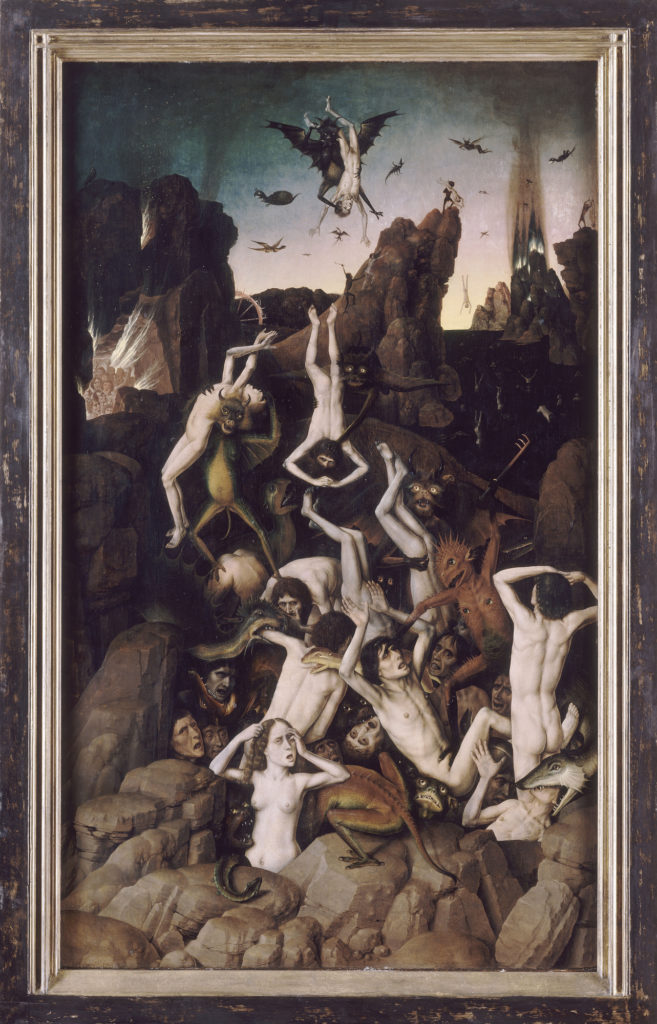

Dieric Bouts, The Fall of the Damned (1468-9). Image © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY. Photo: Jean-Gilles

Berizzi. Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

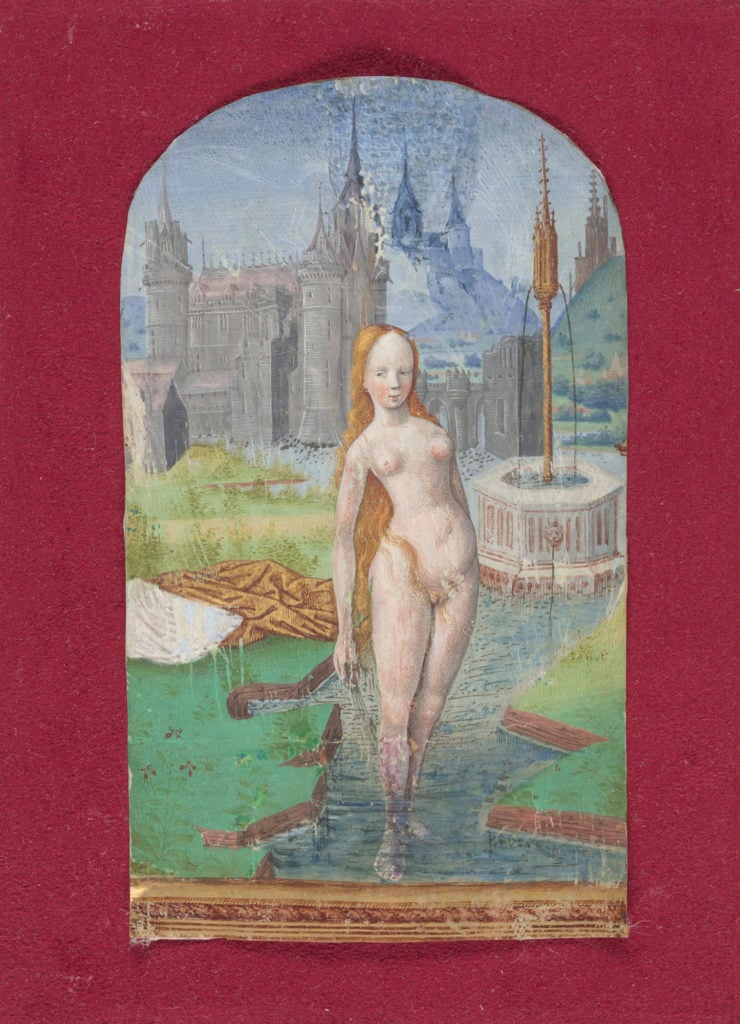

Jean Colombe French, Bathsheba Bathing (ca. 1480).

Hans Memling, Vanitas/Luxuria (1485). Strasbourg, Musée des Beaux-Arts

Photo: M. Bertola.

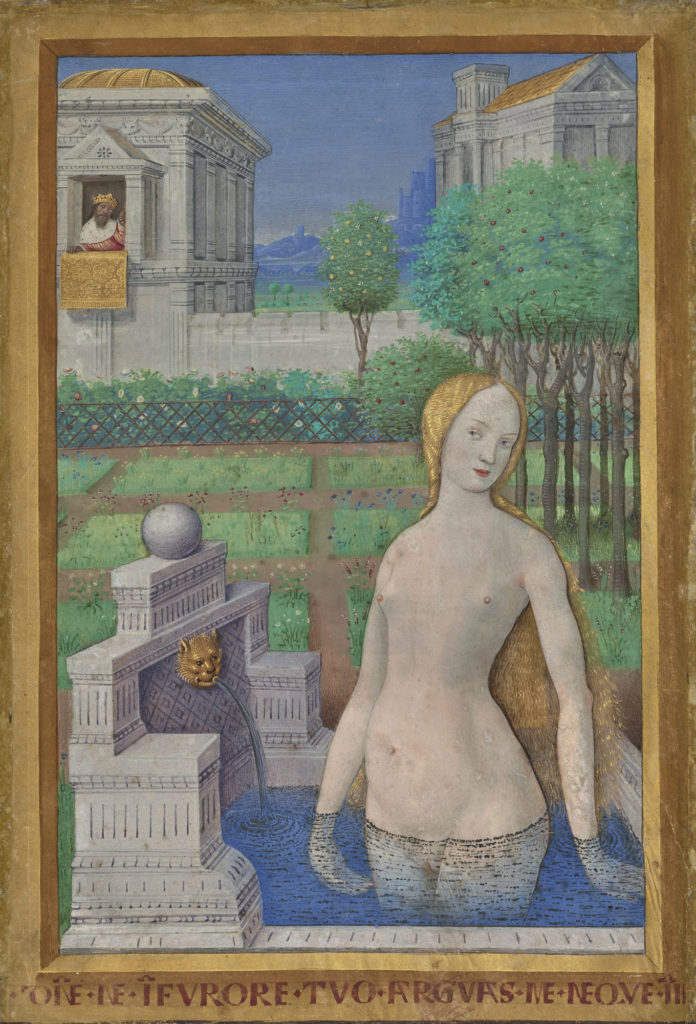

Jean Bourdichon, Bathing Bathsheba (ca. 1498). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Piero di Cosimo, The Discovery of Honey by Bacchus (ca 1499). Image © the Worcester Art Museum.

Giovanni Bellini, Prudence (before 1500). Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

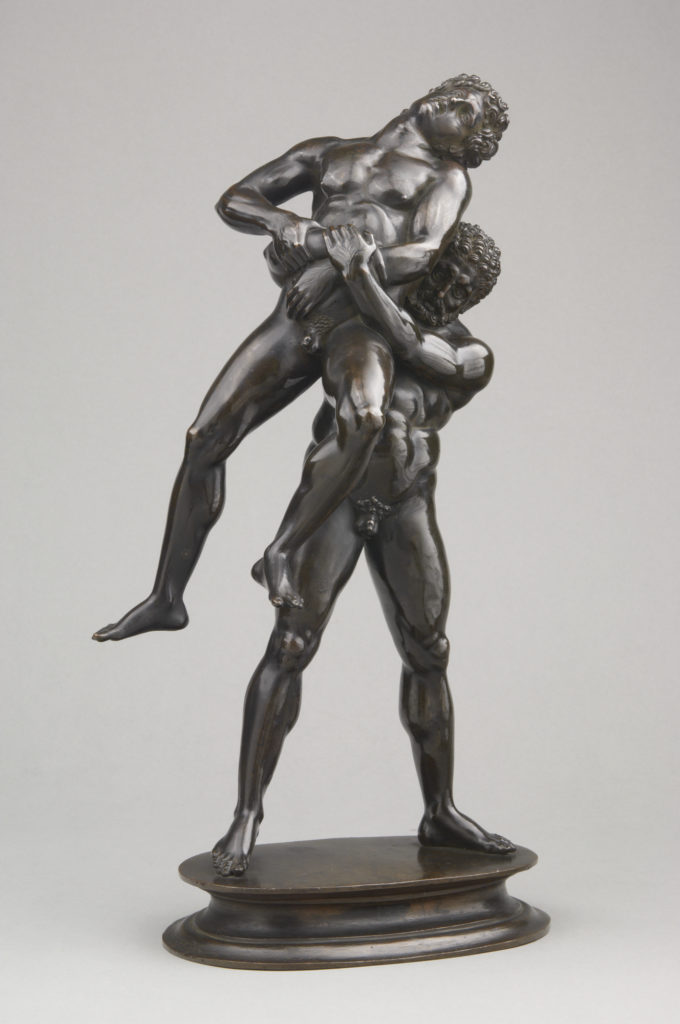

Antico, Hercules and Antaeus (1511/1519). Image: KHM-Museumsverband. Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Jan Gossart, Hercules and Deianira (1517). Image © The Henry Barber Trust, Barber Institute of Fine Arts. Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Hans Baldung, Two Witches (1523).

Dosso Dossi, A Myth of Pan (1524). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

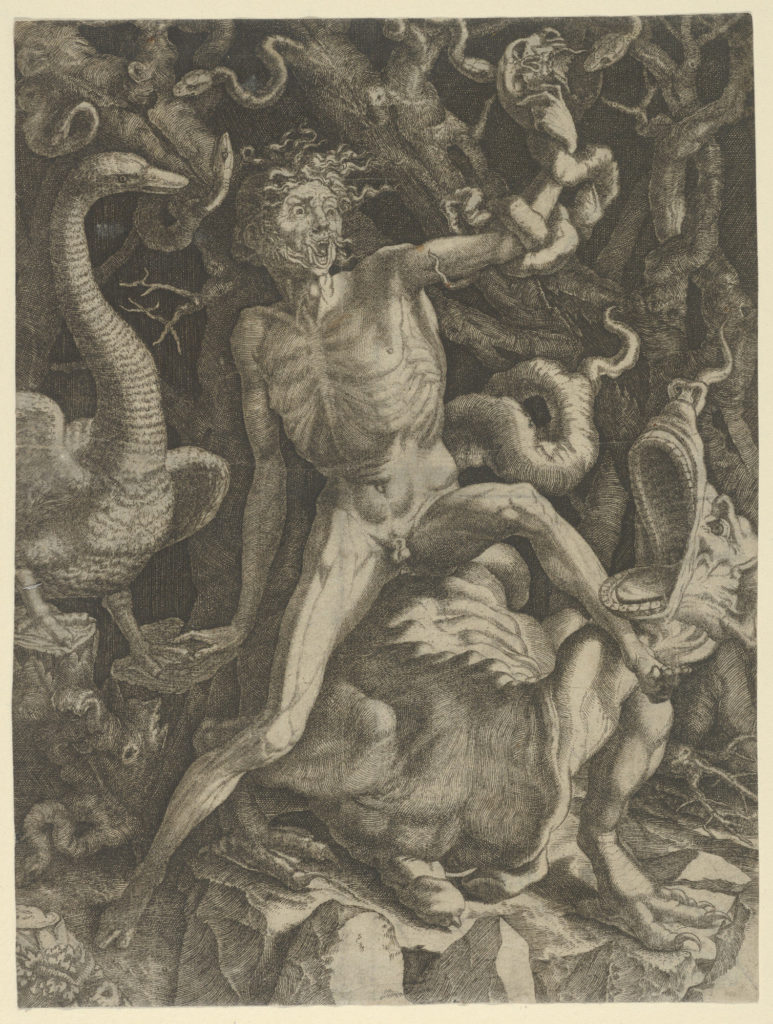

Giovanni Jacopo Caraglio and After Rosso Fiorentino, Fury (ca. 1524-5). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

“The Renaissance Nude” is on view at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, through January 27, 2019.