On View

With Its New Show of Sam Gilliam’s Painting, Dia Wants to Explode Our Assumptions About Minimalism

A new installation of early work by Sam Gilliam will be on long-term view at Dia Beacon starting August 10.

A new installation of early work by Sam Gilliam will be on long-term view at Dia Beacon starting August 10.

Eileen Kinsella

One could argue that a historian’s most important job is not writing history, but re-writing it—pouring back over primary documents to determine who was left out or misrepresented in earlier drafts and correcting the record. By that measure, the historians over at the Dia Art Foundation, who specialize in the art of the 1960s and ’70s, have been extremely busy.

In recent years, the museum has put on shows by artists including Dorothea Rockburne, Michelle Stuart, Anne Truitt, and Charlotte Posenenske; made acquisitions of significant work by Mary Corse and Nancy Holt; and also diversified its spotlights on male artists to include French neon artist François Morellet and the Korean painter Lee Ufan. Now, it is adding another previously overlooked artist to its ranks: Washington Color Field painter Sam Gilliam. The 85-year-old artist has been working for six decades, but has recently been enjoying a career renaissance after a long stretch of institutional neglect.

Sam Gilliam, Spread (1973). Dia:Beacon, Beacon, New York. © Sam Gilliam. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, New York, courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York

On August 10, Dia will unveil an exhibition of Gilliam’s early work from the 1960s and ’70s in Beacon, New York. The presentation includes two “drape” paintings, suspended in concert with one another from the ceiling, and a painting from his “beveled edge” series in which the work’s edges extend off the wall and toward the viewer. The works will be installed within the museum’s permanent collection, putting Gilliam in the context of his minimalist and post-minimalist contemporaries such as Robert Ryman and Mary Corse. The goal is not only to enhance our understanding of who was making minimalist art, but also to challenge the widely held belief that painting took a back seat to sculpture during this era.

“I’ve known Sam’s work since I was a child and the opportunity to curate a show with his work was top of my list,” says Courtney J. Martin, Dia’s former deputy director and chief curator, who oversaw the project before becoming director of the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven this spring. “I probably called Sam the week that I knew I was going to Dia full-time because I knew I wanted to work with him.”

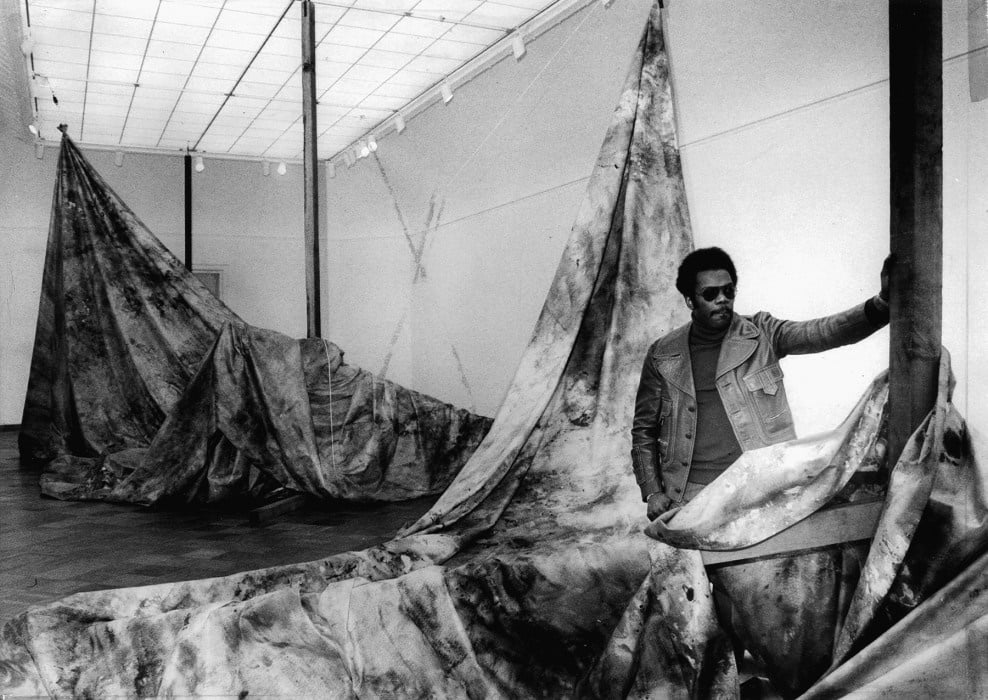

Sam Gilliam, Autumn Surf (1973). Installation view San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1973. © Sam Gilliam. Photo: Art Frisch, courtesy San Francisco Chronicle/Polaris

Gilliam first garnered attention in the mid-1960s for his beveled-edge and drape paintings, which sought to push the boundaries of what a painting could be. He was the first African American artist to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale in 1972.

He is one of a number of painters active in the ’60s and ’70s who were celebrated when they emerged, but receded from view in the ensuing decades due to a mix of factors, including his race and the fact that he worked in Washington, DC, outside of a major art-market hub.

In recent years, however, the art world has appeared to wake up and take notice of Gilliam’s importance. In 2013, he began showing with Los Angeles-based gallery David Kordansky. In 2017, Gilliam returned to the Venice Biennale with a vibrant, unstretched canvas Yves Klein Blue (2017), which welcomed visitors to Giardini’s main pavilion. In 2018, he was the subject of a major retrospective at the Kunstmuseum Basel. Last month, he joined mega-gallery Pace.

Still, his early work in particular remains underexposed in the United States. Martin recalls that, as a young art enthusiast, “I was very taken by works that I’d never actually seen, these early installations where he had these large scale drapes that would take up basically a full room.” The works were site-specific and existed only as installations, meaning that they were rarely shown after their debuts. As a curator at Dia, “I was interested in whether he would want to revisit this idea, come to a place, and figure out its contours and work from there,” she says. Gilliam readily agreed.

The beveled-edge and drape paintings “represent a radical approach to the medium,” says Dia’s director Jessica Morgan. “Architectural in scale, these works chart a crucial moment in Gilliam’s early practice as he explored the possibilities of manipulating canvas in three-dimensional space.”

The works will remain on view at Dia long term to encourage repeated viewings. “My hope was that people walk into the smaller gallery—where the bevel painting is at a 45 degree angle coming off the wall—and feel a compression,” says Martin. “Then you walk into the bigger gallery and feel really loose and free once they see the drape installation.”

The goal is to provide deeper context for Gilliam’s work—and to offer viewers a richer understanding of the art coming out of the ’60s writ large. “I hope that people come to see these works and ask the bigger questions about what happens with Minimalism at a certain point. Dia does a good job, particularly with the works by Donald Judd that are on view. The thing you begin asking yourself is, where was painting at that moment where there is so much conversation around sculpture? Painters were doing super interesting things too.”