On View

An Acclaimed Show at the Whitney Spotlights How Mexican Muralists Shaped US Modernism—See Images Here

While museums are closed to the public, we are spotlighting an inspiring exhibition somewhere around the globe each day.

While museums are closed to the public, we are spotlighting an inspiring exhibition somewhere around the globe each day.

Caroline Goldstein

While museums around the globe are closed to the public, we are spotlighting each day an inspiring exhibition that was previously on view. Even if you can’t see it in person, allow us to give you a virtual look.

What the museum says: “Mexico underwent a radical cultural transformation at the end of its revolution in 1920. A new relationship between art and the public was established, giving rise to art that spoke directly to the people about social justice and national life. The model galvanized artists in the United States who were seeking to break free of European aesthetic domination to create publicly significant and accessible native art. Numerous American artists traveled to Mexico, and the leading Mexican muralists—José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros—spent extended periods of time in the United States, executing murals, paintings, and prints; exhibiting their work; and interacting with local artists.”

Why it’s worth a look: This show, conceived a decade ago and finally brought to fruition, is a testament to the existence of a counter-narrative to the dominant history of the US and Europe as the epicenter of artistic and cultural innovation. The 200 works on display are by both Mexican and American artists, juxtaposing the ways in which the former created a new artistic style replicated by the ladder.

The story of this early form of street art is played out in the massive murals ordained by Mexico’s government to encourage unity in the wake of civil war, encouraging civic pride and a spirit of collective industry. The colorful, eye-catching works inspired US artists to make their own versions, drawing both on the narrative of American exceptionalism, and the underbelly of social and economic turmoil in the 20th century.

With contributions from artists who moved on stylistically from the genre—such as Philip Guston and Jackson Pollock—the show reveals just how popular and important the style was, and the lasting impact it had on the practice of artists like Jacob Lawrence, who chronicled America’s history in a similar manner.

What it looks like:

Installation view of “Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925-1945” at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

Alfredo Ramos Martínez, Calla Lily Vendor (Vendedora de Alcatraces) (1929). © The Alfredo Ramos Martínez Research Project, reproduced by permission.

José Clemente Orozco, Barricade (Barricada), (1931). © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOMAAP, Mexico City. Image © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

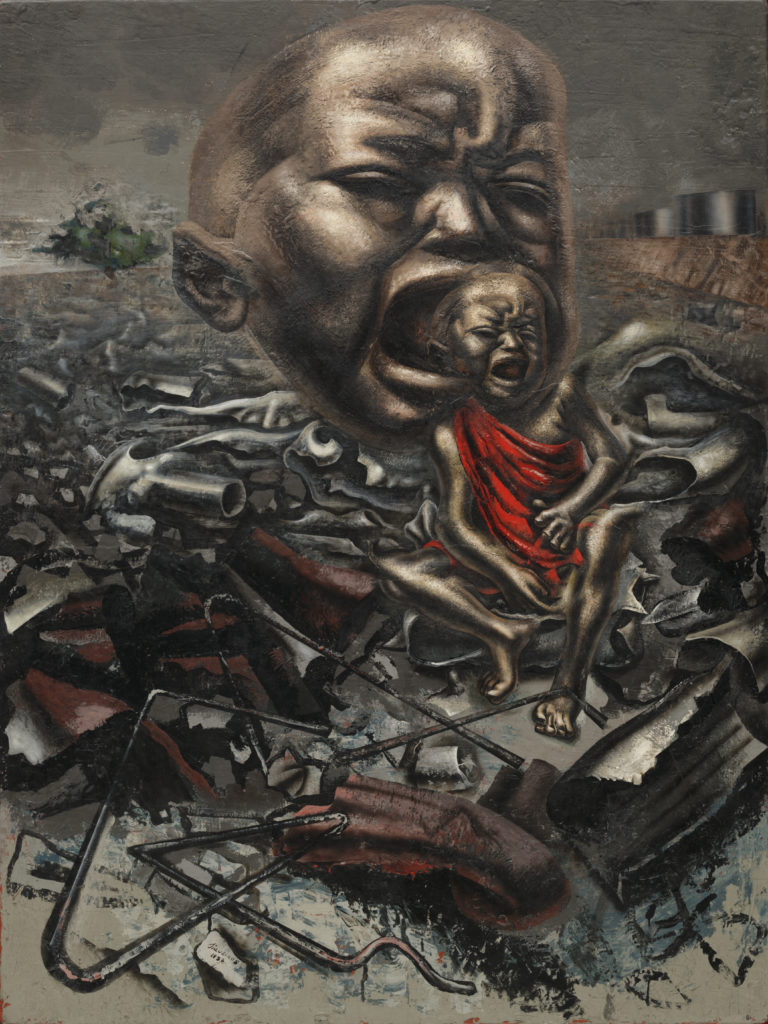

David Alfaro Siqueiros, Echo of a Scream (1937). Courtesy of MoMA.

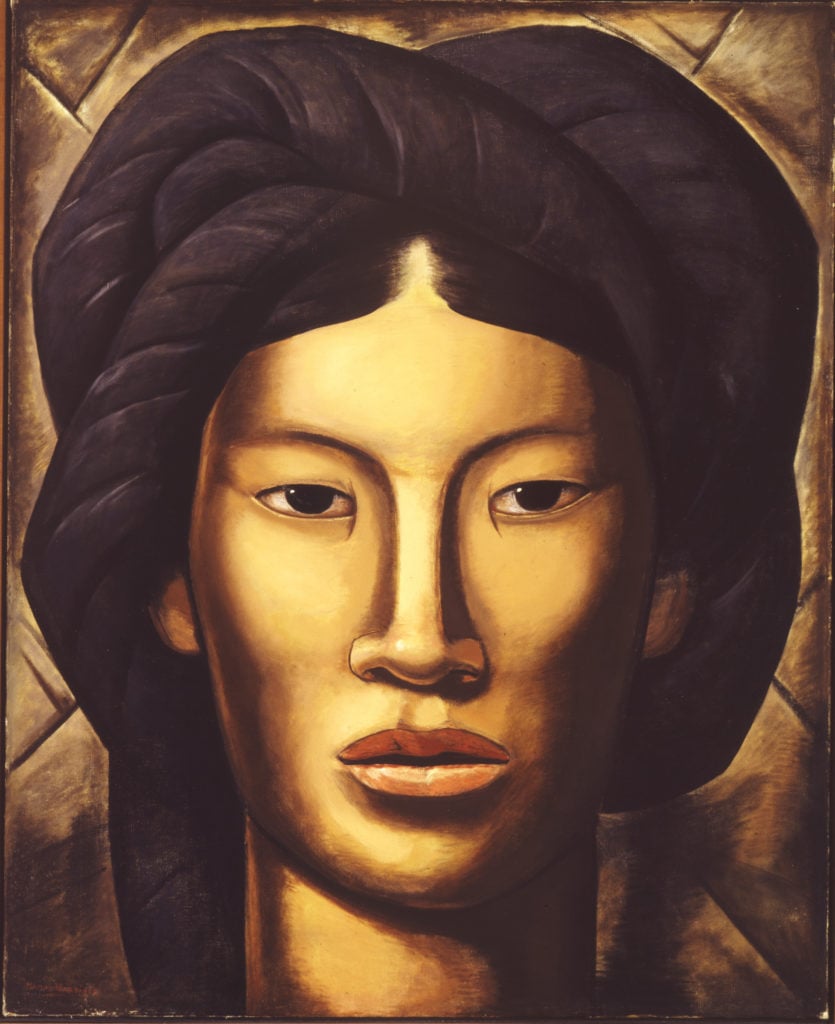

Rufino Tamayo, Man and Woman (1926). Philadelphia Museum of Art. © 2020 Tamayo Heirs / Mexico / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Installation view of “Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925-1945” at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

Jacob Lawrence, Panel 3 from The Migration Series, From every Southern town migrants left by the hundreds to travel north. (1940–41). The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC. © 2019 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Installation view of “Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925-1945” at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

Philip Guston, Bombardment, (1937). © The Estate of Philip Guston, courtesy McKee Gallery, New York.

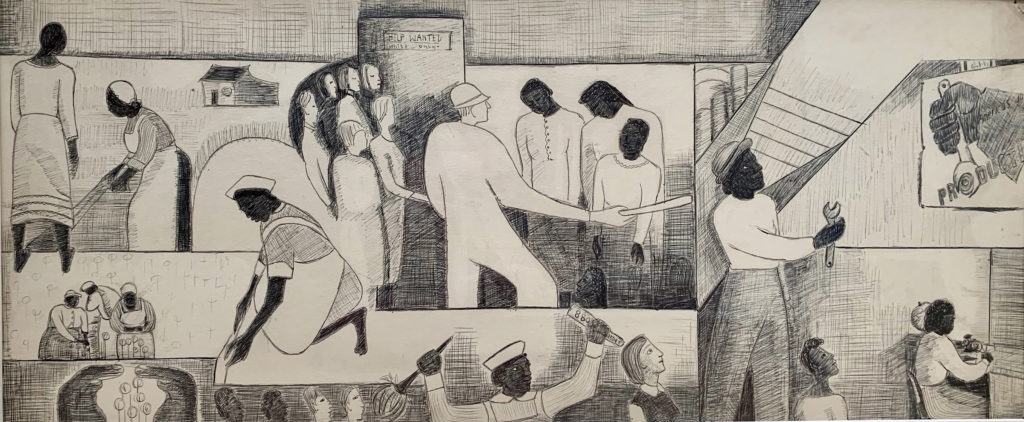

Thelma Johnson Streat, The Negro in Professional Life—Mural Study Featuring Women in the Workplace (1944.)

Alfredo Ramos Martinez, La Malinche (Young Girl of Yalala, Oaxaca) (c. 1940). Collection of Phoenix Art Museum.

Harold Lehman, The Driller (mural, Rikers Island, New York) (1937). © Estate of Harold Lehman. Image: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC / Art Resource, NY.

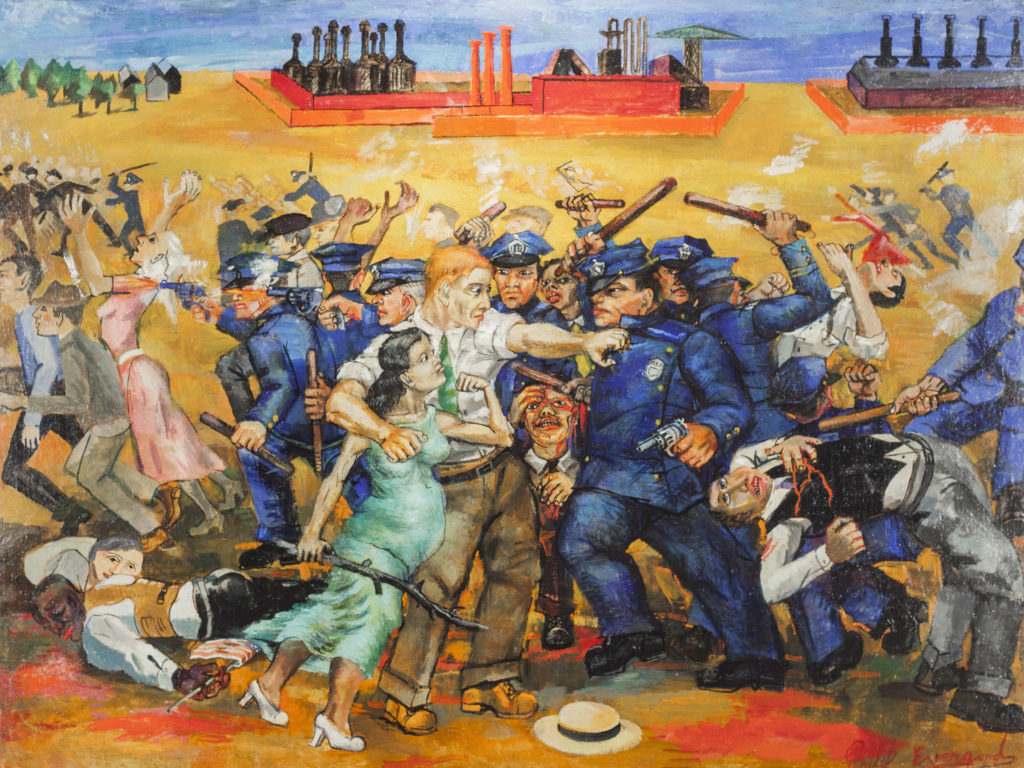

Philip Evergood, American Tragedy (1937). Courtesy of Harvey and Harvey-Ann Ross.

Installation view of “Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925-1945” at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

Installation view of “Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925-1945” at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

Diego Rivera, Man, Controller of the Universe, (1934). Palacio de Bellas Artes, INBAL, Mexico City. © 2020 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

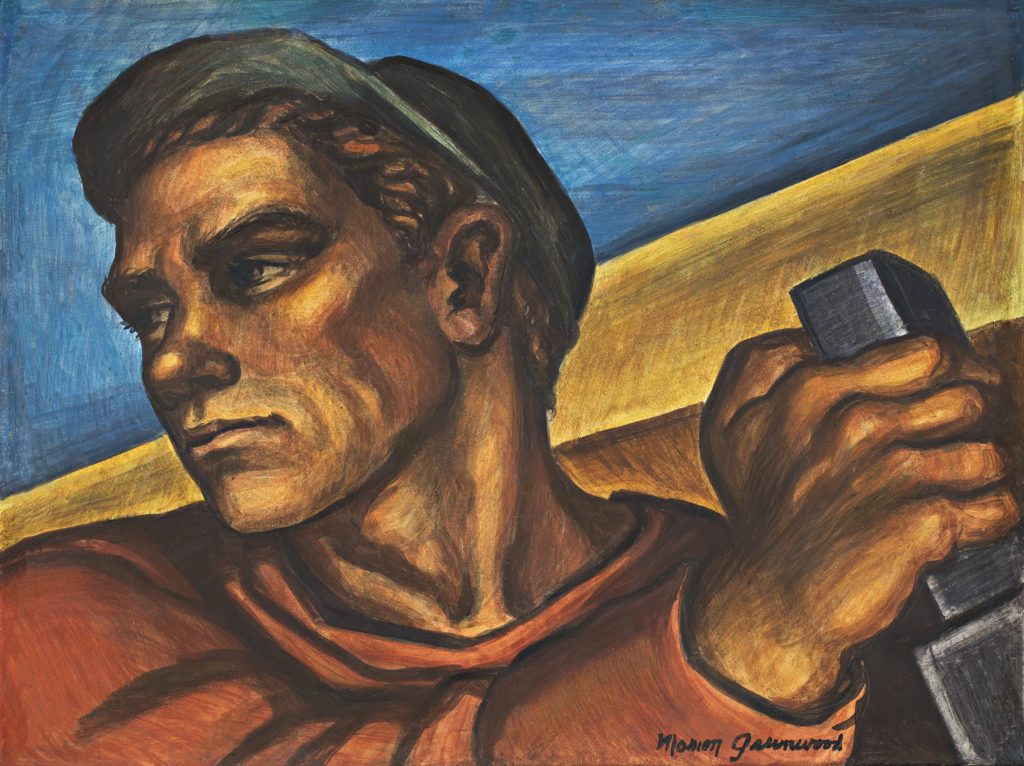

Marion Greenwood, Construction Worker (study for Blueprint for Living, a Federal Art Project mural, Red Hook Community Building, Brooklyn, New York), (1940). Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College.

José Clemente Orozco, Pancho Villa, (1931). Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, INBAL, Mexico City.