Eight red dresses on a clothesline sway back and forth with the wind. Just beyond them is an all-encompassing view of the city of Lagos, with its multitude of shiny skyscrapers, arching palm trees, and pulsating energetic streets. The chic red dresses provide a moment of respite from the cacophony of Africa’s second-most populous city.

The installation is part of Plastic Broken Chairs, Juxtaposed (2019) by Angolan artists Raul Jorge Gourgel and Sandra Poulson on display on the first floor of Independence Building on Lagos Island, a 25-story office building erected by the British government in 1961 as a symbol of its support of Nigerian independence. It is one of the first works you see as you enter the second edition of the Lagos Biennial. Gourgel and Poulson’s wind-responsive installation explores the influence of external bodies on internal dynamics with particular reference to the Angolan Civil War (1975–2002). The artists intend the work to be—as are the other works on show in Independence Building—a case study for nation-building in a post-colonial world.

An installation view of Raul Jorge Gourgel and Sandra Poulson’s Plastic Broken Chairs, Juxtaposed (2019).

Built in reinforced concrete, Independence Building is now on the verge of collapse. Trash, rubble, and old wires can be found throughout the premises, amidst countless debris and graffiti-filled walls. It is the chosen location of the Lagos Biennial, entitled “How to Build a Lagoon With Just a Bottle of Wine?” and taking place until November 23. The show—jointly curated by Antawan I. Byrd, the associate photography curator at the Art Institute of Chicago; architect, interior designer, and author Tosin Oshinowo; and creative producer Oyinda Fakeye—brings together a group of artists, around half of whom are Nigerian, to explore what happens when an artist imagines the future.

An Art of Survival

The biennial takes its name from Nigerian writer Akeem Lasisi’s poem “A Song for Lagos” and seeks to use art to express the people and city of Lagos’s ability to transcend, as the curatorial statement says, “seemingly insurmountable social, political, and economic obstacles.” The gripping and poignant range of works, which unfold across three floors and span photography, video, and works on paper, capture Lagos’s evolution from small lagoon settlement into the mega-city of over 21 million people.

Installation view at the Lagos Biennial, Photo: Malik Afegbua.

The building, located in a central place on Lagos Island, formerly housed major corporations and was also the headquarters of the Ministry of Defense under the administration of Ibrahim Babangida. It caught fire in 1993 and has been deteriorating ever since. In April this year, it was announced that the government would transform it into a federal trade and business center.

In many ways, Independence Building, through its multitude of wear and tear, acts like an artwork itself—interacting with the works on display and providing a powerful reminder of Lagos’s most recent history.

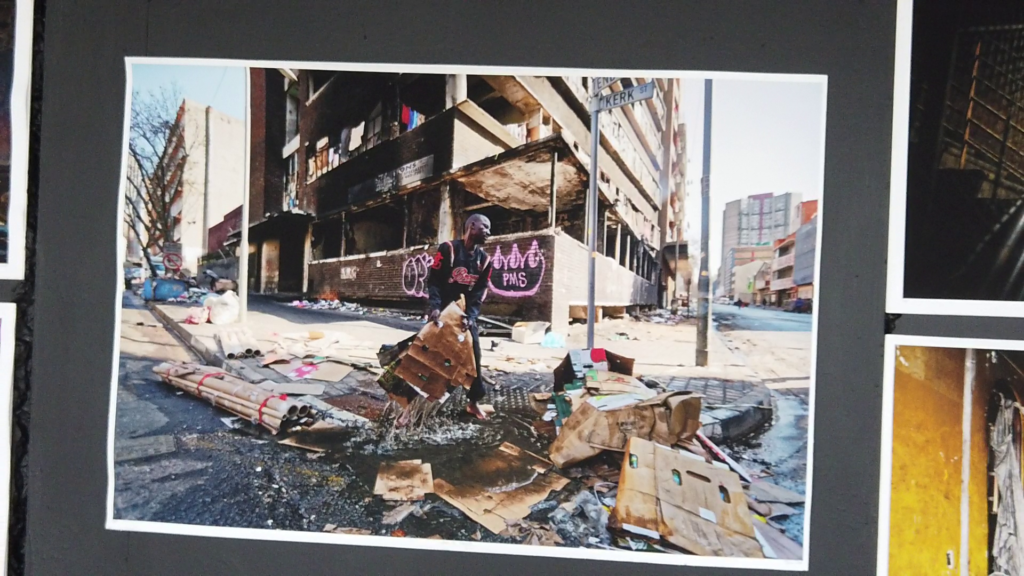

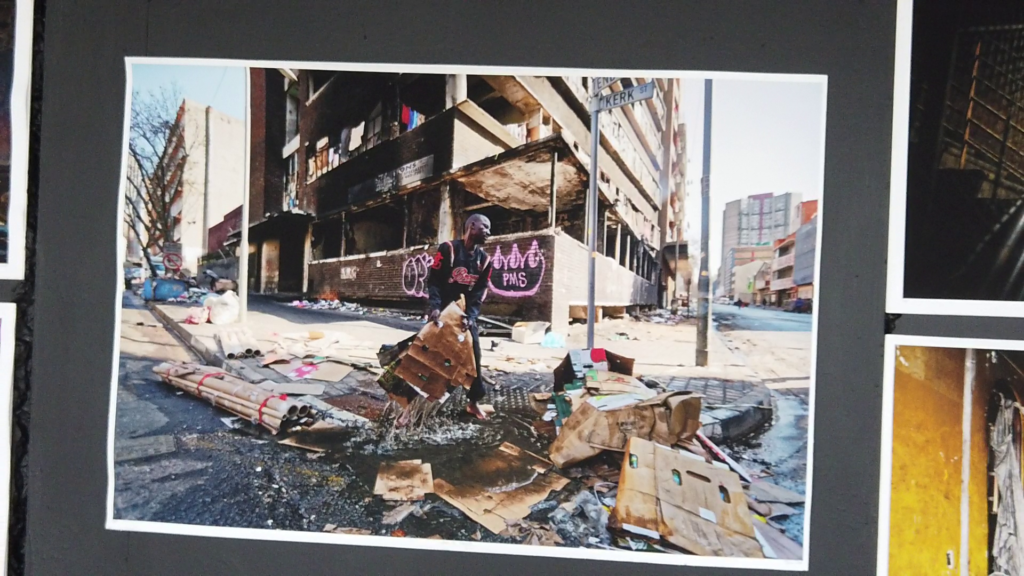

Pedro Pires, Container/Urban (2019). Photo: Malik Afegbua.

In a connecting room hanging over a wall with a pristine view of the city of Lagos is Swiss artist Dominique Koch’s LED sign installation Training Our Mind to Go Visiting (2019) commenting on the work of American biologist and feminist Donna Haraway and her belief in life as symbiosis in which she weaves connections of co-dependency between species, which in turn calls into question the notion of individuality. The work spells out the following message in LED lights: “Teeming spaces and troubled vision make good fiction for thinking.”

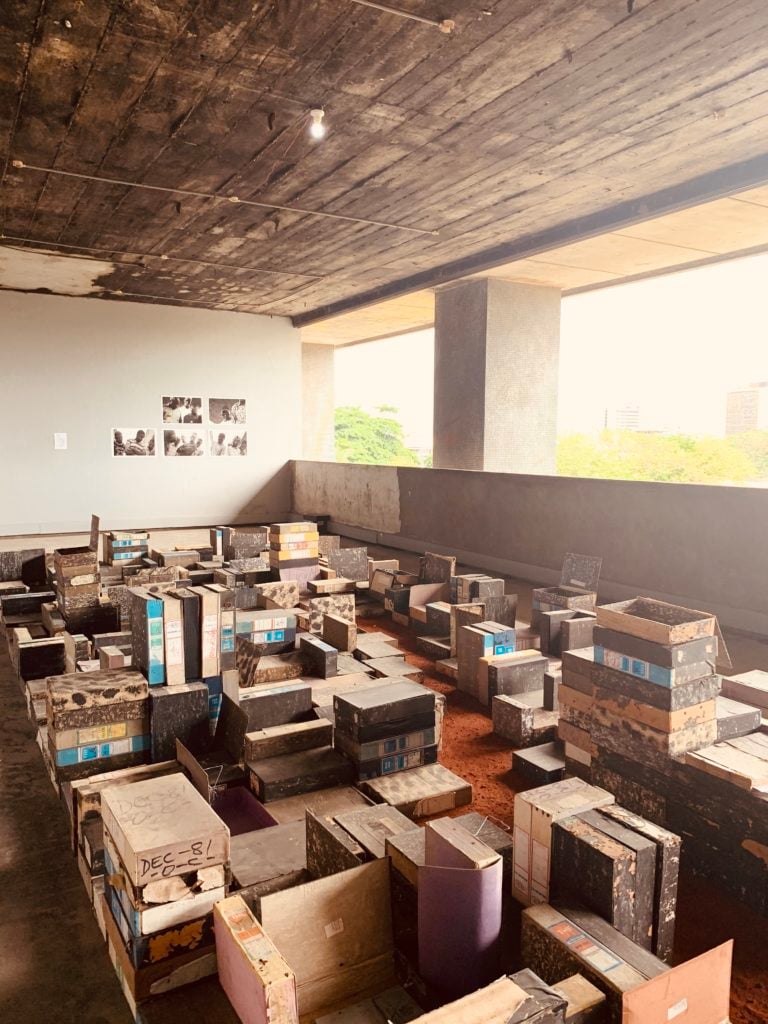

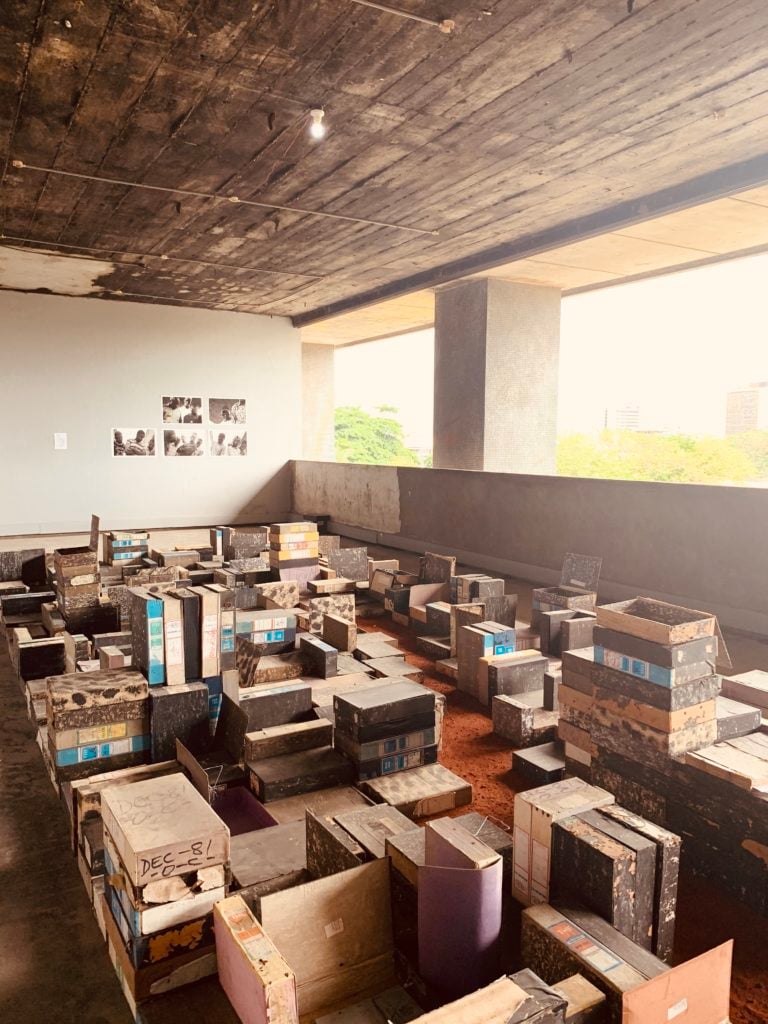

Walk up the dilapidated stairs and in the first room, there is a startling sight: Nigerian artist Ndidi Dike’s A History of a City in a Box (2019), a massive installation of archival photographs, documents, found earth, paper, and wooden file boxes. The installation is based on the artist’s initial site visit to Independence House earlier this year, when she discovered the remnants of an office building’s second floor still containing bureaucratic governmental documents from the 1980s.

“Information is one of the greatest currencies in Lagos,” Dike says. “Information is hidden and buried; it is inaccessible to the people, and only permitted to those in power.”

Ndidi Dike, A History of a City in a Box (2019). Photo: Malik Afegbua.

As a precondition of the building’s use for the biennial, the office Dike discovered had to be closed off with plywood in order to conceal these documents. Her installation is a reflection on such information, how it has been lost and hidden, and ultimately, the aesthetics of bureaucracy in Lagos. What many may not know is that, during the colonial era, hundreds of such boxes were introduced in order to protect and conceal information.

Living on the Edge

“To fill a lagoon with a bottle of wine, without money etc… this is a miracle,” states the text for Miracle Room, a life-size scroll that acts as a personal temple in one of the nearby rooms colored in gradations of yellow and orange. “It is a place of personal expression, where you detox off the city and prepare yourself to battle to the death with the forces it throw at you,” continues artwork’s statement. Like a magic box, the installation, made by Nigerian architectural collective HTL Africa, offers a moment of interactive enchantment—a few minutes of renewal from living on the edge.

The Lagos Biennial was initiated in 2017 by artist Folakunle Oshun with the aims of creating an “indigenous biennale” in Nigeria. The biennial is a nonprofit contemporary art platform under the Àkéte Art Foundation, a Lagos-based artist collective registered with the Corporate Affairs Commission in Nigeria.

“It arose then as a joint effort,” Tosin Oshinowo said. She recalled that the first Lagos Biennial was held in a disused railway compound that has a similar character to this year’s site. “Both locations foster nostalgia for a time past,” she said.

Installation view at the Lagos Biennial, Photo: Malik Afegbua.

Stationed in another room with a view are two sculptures made with found materials by Angolan artist Pedro Pires. At the bottom of both totem pole-like installations are locally sourced plastic boots onto which are placed plastic boxes and buckets.

“My aim is to create an anthropomorphic volume that invites the public to rethink the aesthetic and utilitarian value of these objects, and how they impact our lives,” Pires explained.

One of the most poignant works is by Nigerian artist Temitayo Ogunbiyi—You Will Find Playgrounds Among the Palm Trees (2018–19) is a series of interactive sculptures placed on the roof and made from a variety of large-scale anamorphous-shaped sculptures in cast bronze and galvanized steel piping wrapped in twine that relay the need to create platforms for play using techniques found in threading hairstyles.

Temitayo Ogunbiyi’s You will find playgrounds among palm trees (2018-19).

In a fascinating commentary, the interactive sculptures, which seem to move before one’s eyes against a backdrop of towering skyscrapers, also refer to the supposed history of enslaved Africans transported to Colombia who would braid escape routes into their hairstyles.

“Despite the country’s economic instability, Lagos has constantly expressed her resilience to transform and adapt,” Oshinowo said. “It is the nature of the city’s resilience that speaks to a creative renaissance and cultural awareness of self and place and that’s the theme of this year’s show.”

The Lagos Biennial is on view to the public through November 23.