For the first time, the Turner Prize exhibition is entirely devoted to the moving image, with works by the four nominees all lovingly installed in black boxes at Tate Britain in London. It is also one of the most politically engaged exhibitions in the prize’s more than three decades.

The eagerly anticipated exhibition of works by Forensic Architecture, Naeem Mohaiemen, Charlotte Prodger, and Luke Willis Thompson, which opens to the public on September 26, takes a whopping five hours to view in its entirety. Perseverance will be rewarded: This is probably the most consistently brilliant Turner Prize exhibition I remember seeing. I left Tate Britain feeling not exhausted but mindblown by the quality, relevance, and poignancy of all the works included.

Luke Willis Thompson

Luke Willis Thompson, Autoportrait (2017), installation view, Chisenhale Gallery, courtesy of the artist. Photo by Andy Keate.

The themes of truth, testimony, and memory—both historical and personal—underpin and connect the four presentations. Luke Willis Thompson (born 1988) is showing three 35mm films that deal with issues of race and police brutality. Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries (2016) features two black-and-white portraits of young men related to women, Dorothy “Cherry” Groce and Joy Gardner, who were killed by police in their London homes. (Groce was shot in 1985, sparking the Brixton Riot, while Gardner died after a botched deportation.)

Then comes the film that made the artist famous (or infamous, depending on who you ask), and which earned him his nomination: Autoportrait (2017) shows Diamond Reynolds, who live-streamed via Facebook the fatal shooting of her boyfriend Philando Castile by a police officer during a traffic stop in Minnesota in 2016. With their muted, direct gazes, these depictions have been widely compared to Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests. But Willis Thompson shows his subjects in a starker contrast of light and shadow, which brings to mind Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro, a technique that renders them almost statuesque.

Willis Thompson’s newest film is a departure. Called _Human (2018), it is a detailed study of a miniature house crafted in 1997 by the artist Donald Rodney with a fragment of his own skin precariously held together with cellophane and pins. Here we see the sculpture by a key figure of the British Black Art Movement, shot in color rather than a countenance in black and white. By immersing all his subjects in silence, only broken by the rickety noises of the projector, the New Zealand artist somehow equalizes all of them as muted objects, loaded with meaning, yes, but silenced nonetheless.

Willis Thompson’s work is, indeed, problematic—which according to his critics is compounded by the fact that he is not black. (The artist, who has European and Fijian heritage, doesn’t identify as white.) But to me, these works seem more empathetic and holding than exploitative.

Forensic Architecture

Forensic Architecture, Killing in Umm al-Hiran (2018). Courtesy of Forensic Architecture.

Nearby, the Goldsmiths-based collective Forensic Architecture is presenting The Long Duration of a Split Second, a two-part project that deals with the Bedouin communities in the Negev/Naqab desert in southern Israel. The main project, Killing in Umm al-Hiran, 18 January 2017, began as a means to clarify what exactly happened on the night hundreds of Israeli policemen raided a Bedouin village to demolish a few houses and two people ended up dead: a villager called Yakub Musa Abu al-Qi’an and an Israeli police officer called Erez Levi. Israeli police claimed that Abu al-Qi’an had attacked a group of policemen with his car, but residents and activists argue that police fired first. Compiling footage and sound clips recorded by witnesses, as well as interviews, models, press clippings, and even a reconstruction of the event, Forensic Architecture was able to prove that police had, indeed, opened fire first. No police officer was charged as a result of the official Israeli investigation. Despite having been nominated for the UK’s most prestigious art award, the research agency is resolute in its refusal to aestheticize projects. Its presentations are dry, functional, and sobering, never losing sight of their use beyond the art world, in citizen tribunals and human rights processes.

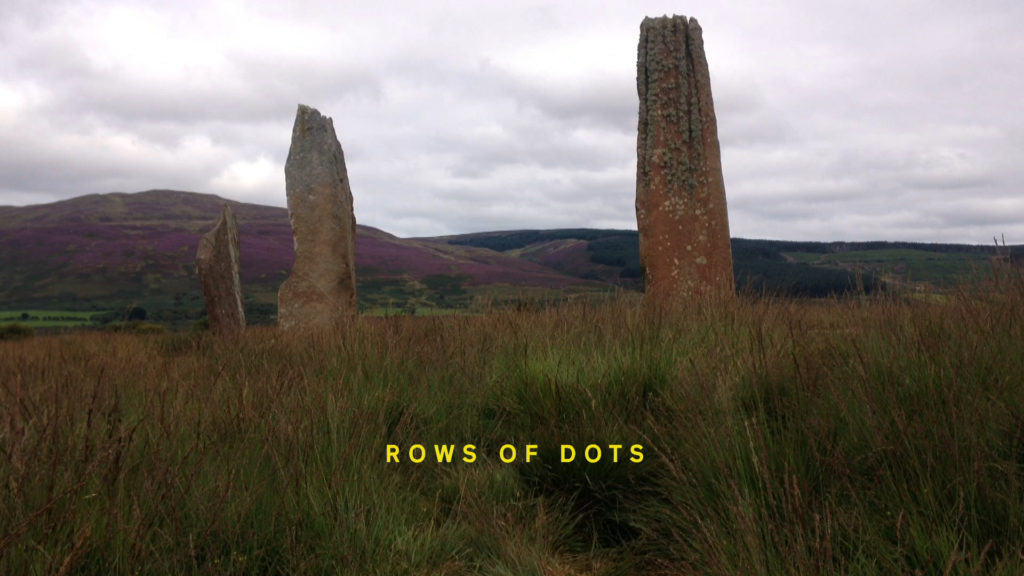

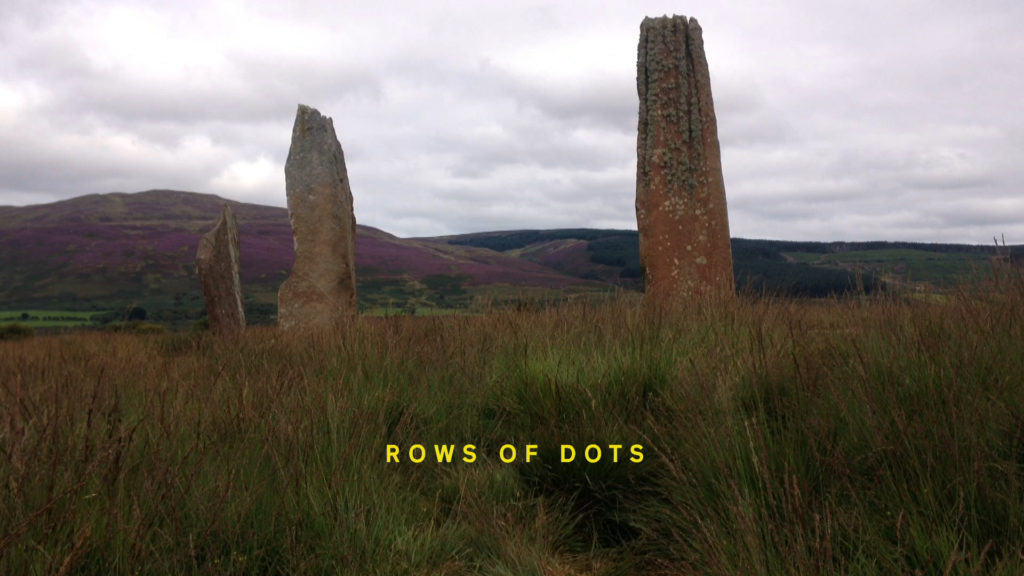

Charlotte Prodger

Charlotte Prodger, BRIDGIT (2016) video still, courtesy of the artist, Koope Astner, and Hollybush Gardens.

BRIDGIT (2016) is an intimate, autobiographical 33-minute video that Charlotte Prodger (born 1974) shot entirely with an iPhone over the course of a year. Scenes of mundane activities are interspersed with shots of Neolithic sites across rural Scotland, where the artist grew up. Voice-overs by Prodger and her friends narrate confessional texts about growing up, coming out, fumbling and then grasping a sense of identity, as well as extracts written by historical queer figures. BRIDGIT, titled after a Neolithic goddess, seamlessly weaves everyday observations with mythical beliefs, conflating body with landscape in a piece that is deeply moving despite its simplicity, or precisely because of it.

Naeem Mohaiemen

Naeem Mohaiemen, Two Meetings and a Funeral (2017), installation Hessisches Landesmuseum, Kassel, documenta14. Photo, Michael Nast.

Naeem Mohaiemen (born 1969) is showing the two films that he presented at documenta 14 last year. Tripoli Cancelled (2017), his first foray into fiction, is an exquisitely observed 90-minute look into the life of man stranded for over a decade in an abandoned airport. But it’s the three-channel video Two Meetings and a Funeral (2017) that really steals the show. The 89-minute documentary is a tour de force exploring the struggle that took place in the mid-’70s between the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). By combining historical footage with contemporary testimonies, the piece laser-focuses on the interference of the OIC as a key factor in the failure of the Non-Aligned Movement, creating the conditions whereby some developing countries felt compelled to pivot away from socialism and embrace Islamism as a unifying ideology. Resisting an omniscient perspective and letting the protagonists speak, Mohaiemen expertly charts a shift of the utmost importance in today’s geopolitical landscape.

It’s a much-needed exercise in remembering in an era of acute sociopolitical amnesia. While the other three nominees effectively inspect issues of institutionalized violence and identity through individual case studies, the scope and ambition of Mohaiemen’s work set it apart in these politically fraught times.

“The Turner Prize 2018″ is on view from September 26 through January 6, 2019, Tate Britain, London. The winner will be announced on December 4.