On View

‘There Hasn’t Been a Lot of Improvement’: Feminist Artist Valie Export on Why She’s Rebooting Her 1980 Venice Biennale Pavilion

The provocative installation is now on view at Galerie Thaddeus Ropac in London.

The provocative installation is now on view at Galerie Thaddeus Ropac in London.

Naomi Rea

The artist Valie Export sits across from me in an apartment above Thaddaeus Ropac’s London gallery, which is currently hosting an exhibition of her work.

Export, whose given name is Waltraud Lehner and married name was Waltraud Höllinger, shed her previous male-oriented names back in 1967. She began to call herself Valie, a nickname for Waltraud, and appropriated a new surname from a popular brand of cigarettes

Export and artist Maria Lassnig were the first women to represent Austria at the Venice Biennale, in 1980. Then 39 years old, she had made a name for herself through provocative films and performances in the 1960s and ‘70s, during the heydey of the transgressive interventions of the Actionists. Most famous were her performances of what she termed “expanded cinema,” a group of works that took on the sexualizing male gaze which had framed the way women were treated in film and society.

These radical interventions included the historic performance TAP and TOUCH CINEMA (1968), in which Export invited passersby on the street to reach into a small curtained theater box constructed around her naked torso. But she is best known for another performance, Action Pants: Genital Panic, which saw her enter an art-house movie theater in Munich wearing crotchless pants and defiantly stare down the audience.

These actions shocked conservative Austrian society, as did her avant-garde biennale presentation which included a black-and-white film of the ritual of the eucharist. It played on a television perched near a pair of splayed female legs, from whose crotch erupted a red neon strip. This Birthbed was surrounded by photographs from Export’s “Body Configurations” series, and “HOMOMETER,” in which she restaged religious scenes featuring women and domestic appliances (advertising during the period often positioned these appliances as the housewife’s “salvation”).

Forty years on, Export’s entire Venice presentation has been restaged at Galerie Thaddeus Ropac in London. The now 79-year-old artist sits down with Artnet News to reflect on how things have changed—and haven’t—in the decades since the work was first exhibited.

Valie Export, Geburtenbett (1980). Photo: ©Valie Export/Bildrecht 2019. Photo by Ben Westoby, courtesy of Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac.

This installation was first staged in Venice 40 years ago. Why do you think it is important to show it again now, at the end of 2019?

Every installation has its own language, its own expression. It’s an ongoing question, of course, especially if you go back in the history of painting and sculpture. You wouldn’t ask the same question if one were to re-exhibit a Rodin sculpture or a Kiefer painting. In my case it is an installation.

It is always interesting to go back to a work of art and see how the reactions might have changed or the message that was initially sent out is received in a different way. For me it is very interesting to regard these works for the first time and again, to see what the actual new voice of the installation is. It’s normal and legitimate to exhibit so-called historical works again and I would dare to say this is a historical work.

The original reaction to the work was quite strong. What was that like for you? Were you expecting it?

In Venice I did not expect anything. I worked with media, I worked with feminism, I worked with my body. I decided to make two installations. I had another installation in another room, and then I had Birthbed. For me it was great to show the context of birthing, of the female body. It’s not my own body though.

It was the combination I found intriguing, in the sense that it was both the birth of the female body, incarnated by the sculpture through the spread legs, neon lights, the blood coming out, the blood with its own different symbolic meanings. And on the other hand, it was the host, the bread from Catholic mass, which symbolizes the creation of the male body.

The work is now being exhibited in a commercial gallery. Do you have an idea where you would like to see it go after this?

I had [Birthbed] outside once at the Mumok in Vienna. But the full installation is not fit to stand outside. You would have to repair it all the time, of course. The material is durable, but you do have to maintain it for it to stay exactly the same. I would wish to see it in a museum permanently—to have the work in its own room. Although it can also be shown alongside other works. The sculpture also works without the “Body Configurations.” You could show it on its own, you could show it with other works—or with other works by other artists.

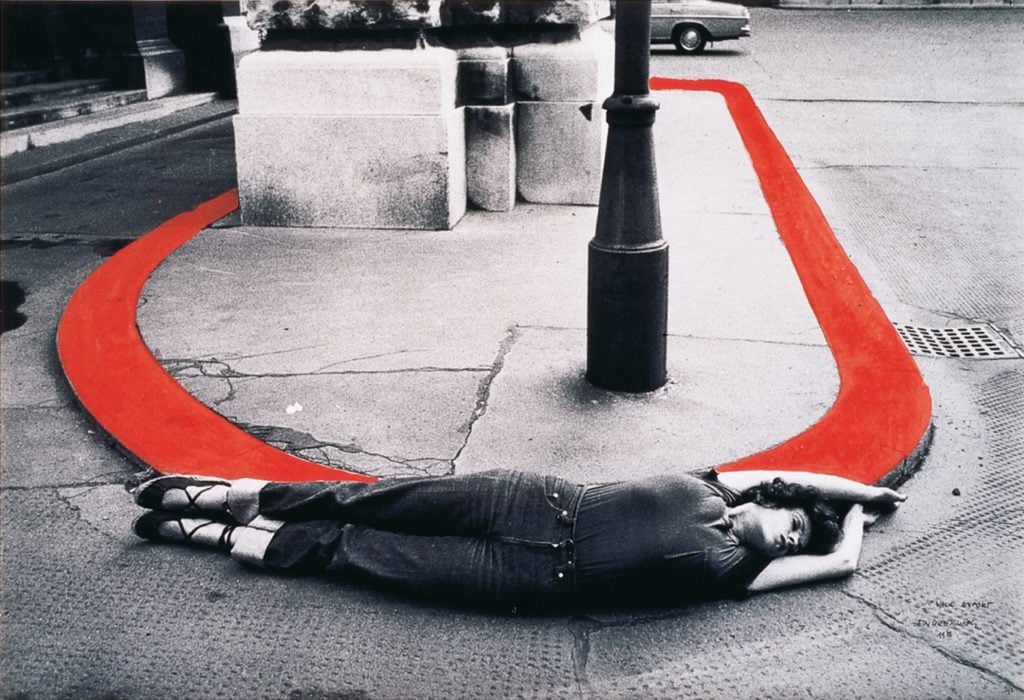

Valie Export, Einkreisung (1976). ©Valie Export/Bildrecht 2019. Photo by Ben Westoby, courtesy of Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac.

In “Body Configurations” you contort your body, which is visibly female, to fit in with the inflexible male architecture of the city. How do you think that both physical and social architecture has evolved to accommodate women in the years since you first made the series?

There have been changes, certainly. There are two parts of architecture in the series, or possibly even more. There are the traditional buildings such as the Ministry of Justice, the parliament, the public library. And then there are buildings from the post-war period. Of course things have improved, not that the female body is better represented throughout society, but women are increasingly part of the new structures that are created through architecture.

There were almost no female architects at the time I created the series; now there are more female architects. Nevertheless, it is very curious to observe a certain glass ceiling in architecture. Female architects are not invited to build historic buildings, with historic meaning or symbolism, and they often don’t build on the most prominent sites. The buildings they build are often not in the right environment. Female architects often don’t win the final competition to realize a project.

In addition, the jury of these competitions is very often male dominated. It might be an inherent thinking structure in these mostly male juries that they consider men as better at those historic categories. It reflects the fact that women are not part of history. We don’t let them build the buildings that define the way we see history. We deprive women of the language and of forms of expression. In a way, male architecture has its own language.

During [pavilion commissioner] Hans Hollein’s introduction to your Venice Biennale presentation, he noted how women’s role in art was being better recognized, which is a conversation that feels like we are still having today. When it comes to women’s role in the art world, how do you think things have changed since the 1980s?

I don’t want to be so negative, but there hasn’t been a lot of improvement. An image has been created to suggest things have changed but really they haven’t. It’s just an image.

There is a certain community of male collectors who solely support male artists. These circles strive to perpetuate the male power structures. There is very little support in male structures toward female artists unless maybe someone thinks that the prices might go up in the future. It’s often in the future with female artists, while for the male artists it’s often already interesting in the present. With female artists it’s a speculation. Maybe it will “go up” in the future.

Your relationship with Thaddaeus Ropac is just a few years old. Why didn’t you have gallery representation before?

It was not like I didn’t have galleries. There were galleries in the past and I still work with certain galleries along with Thaddaeus Ropac. I have to say, at the very beginning I was not so much interested in working with galleries because I wasn’t sure I’d fit into their policies. Every gallery has its certain policy and its certain program. I didn’t want to adapt because I wanted to be independent from these kinds of political decisions, such as where to exhibit. From the very beginning I was not very keen to develop a big network of galleries around me. Later, when Thaddaeus came to me and offered a possibility to work together, I considered it and accepted it quite quickly because Thaddaeus is an Austrian gallerist but on an international scale, which would give me the possibility to exhibit my work internationally. It makes sense to open up to an international gallery and to have representation that brings my work abroad. Of course, this is also in his interest.

Valie Export, Die Geburtenmadonna (1976) (after Michelangelo Buonarroti’s Pietà, Madonna della Febre, 1498-99). Photo: ©Valie Export/ Bildrecht 2019. Courtesy of Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, photo by Ben Westoby.

I can give another example, I was a filmmaker—still am a filmmaker—and when I produced my first film it was very underground, without a license. But the trade chamber came to me and said if I made films I couldn’t travel with them unless I had an official license to feature films—there were too many obstacles. I would have had to go through various diplomatic stages to obtain support from the cultural institution. It wasn’t feasible commercially. Then, for my second film, I went to a production company and co-produced my film with them. But then I was told what I had to cut and how long a shooting day could be, what could or couldn’t be added. The producer intentionally spoke so quietly that I could barely understand him. It was such a hassle to work with this production company, I didn’t like it. And so I decided to make my own production. In two weeks, I learned everything. I wasn’t familiar with running a company and the regulations but I learned to adapt. I was one of the first female film producers with a diploma.

In the exam there was this question about the triangles. The triangle is this procedure where you have three different negatives to make copies of the film. While I was thinking about what a triangle is, the male jury member was already giving the answer before I could say a word, telling me “you don’t need to know this because a triangle is not something you will ever experience, this is more for films with a bigger scope. It’s for filmmakers with a certain international distribution.” In the end the jury said to me, “you would technically pass with distinction because this was a very good presentation but since you are an artist and on top of this a woman, you won’t get the distinction.”

I want to say another thing about Ropac—I was very happy with the start I got at the gallery because as soon as it was decided that I would join the gallery, they immediately started to exhibit my work and the ideal of my work is to export it into the world. We had a show in Paris, in Salzburg, and now in London. It worked immediately and that is of course very pleasing.

You were part of a wave of feminism that was invigorated during the summer of 1968. I have heard people talking about how the spirit of 1968 is alive today, through the yellow vest protests in France, the unrest in Hong Kong, and movements such as #MeToo. Do you feel the energy of 1968 today?

That time is gone. There is no student revolution, there is no revolution or rebellion against the state or state laws—no revolution in the air. There is not much going on in Europe. But in small groups—or when you talk to people, as I recently did in Florence when I visited the anti-violence convention—the resistance of women manifests much more strongly. Young men also embrace the mission of feminism. I hope that the young generation will closely observe the sociopolitical, cultural-political situation in their countries and take it to a global level. We are now in a global society so we should address these issues together.

“Valie Export: The 1980 Venice Biennale Works” is on view at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London, through January 25.