On View

Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro’s Epoch-Making Feminist Installation ‘Womanhouse’ Gets a Tribute in Washington, DC

"I don't know that I realized how radical a change I was going to make," Judy Chicago says.

"I don't know that I realized how radical a change I was going to make," Judy Chicago says.

Sarah Cascone

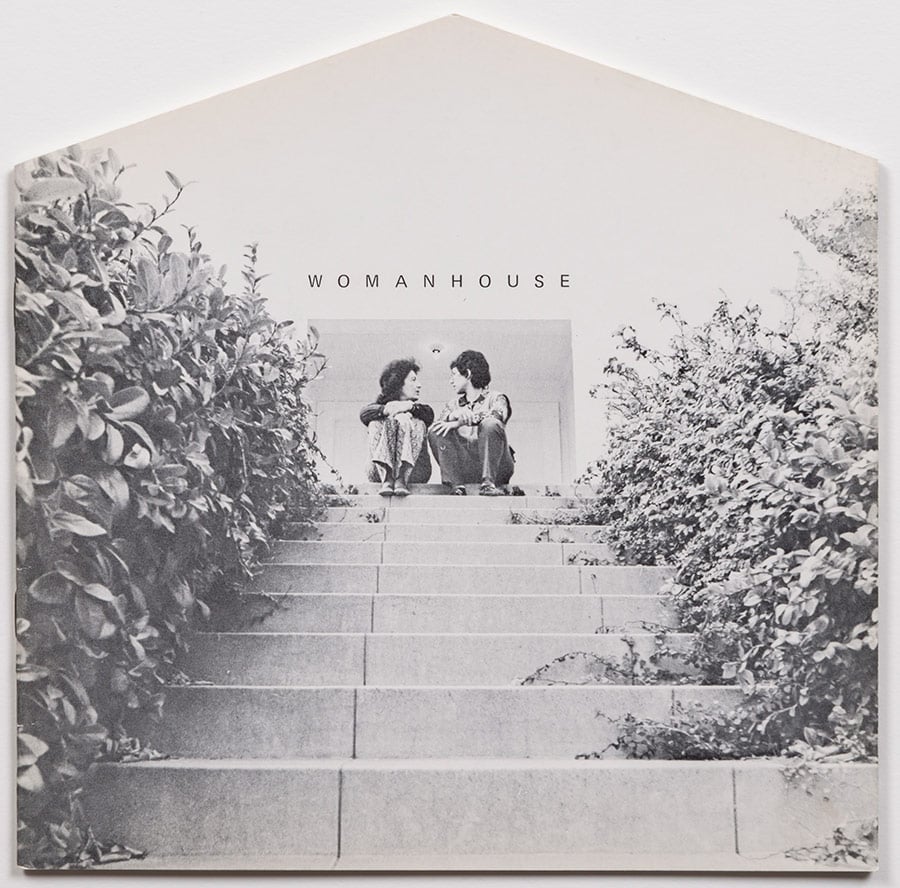

It would be hard to imagine better timing for the opening of the show “Women House,” a 21st-century take on artists Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro’s original 1972 installation, Womanhouse, which they made in collaboration with their students at the CalArts Feminist Art Program in Los Angeles.

The new show, which opened last year at the French museum La Monnaie de Paris and is now traveling to the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC, comes in the wake of the #MeToo movement and, in the US, just after International Women’s Day. But the curators had no idea how much their efforts would tap into the cultural zeitgeist when they first started planning the show back in 2015.

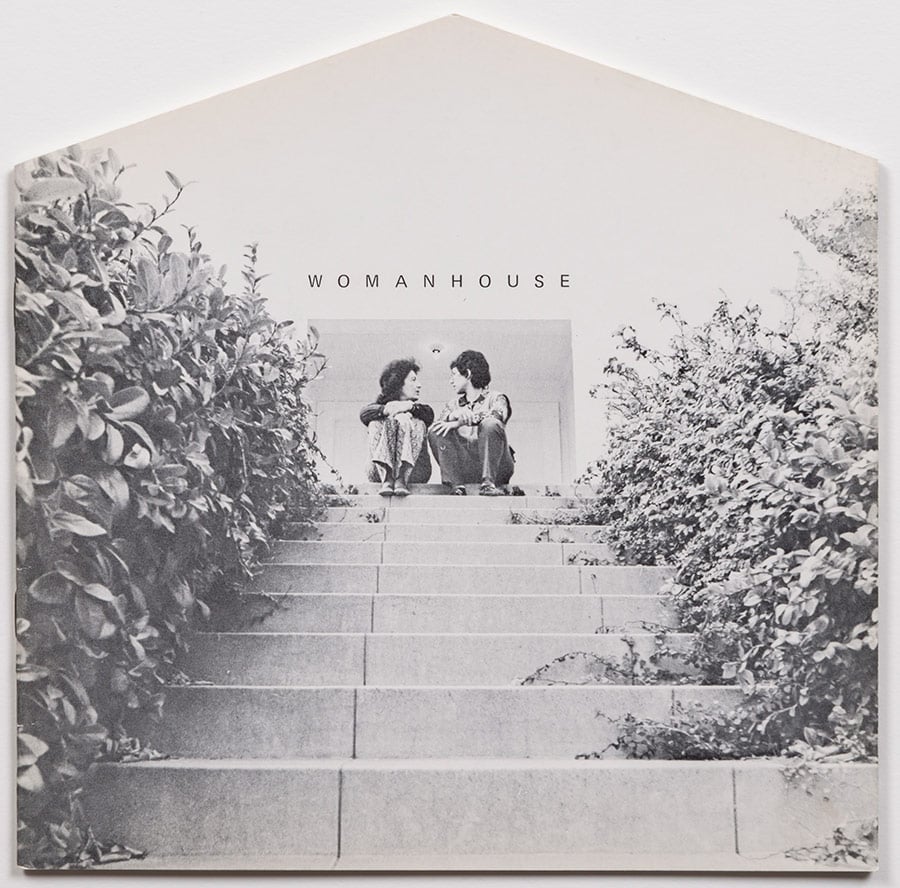

Judy Chicago, Butterfly, test plate #2 (1973–74). Photo by Donald Woodman, courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York. ©Judy Chicago.

“No one realized it was going to coincide with such an important moment for cultural change in regards to women in the workplace,” said Orin Zahra, an assistant curator at the museum. “The show will resonate more because of this current spotlight on women’s issues, even though it’s not directly talking about sexual harassment. It’s about how architecture is politicized—and you see that both in the domestic space and the work place.”

Chicago similarly had no idea what a surprise hit her original Womanhouse, which addressed stereotypes about home and femininity, would be either. “I don’t know that I realized how radical a change I was going to make,” she told artnet News. “In the 1970s, the two biggest issues were sex and housework. Since then, more women have entered the work force and have been battling against the glass ceiling and experiencing our form of male terrorism, which is sexual harassment.” In some countries, women still aren’t allowed to leave the house, she added.

Zanele Muholi, Katlego Mashiloane and Nosipho Lavuta, ext.2, Lakeside, Johannesburg

Zanele Muholi, Katlego Mashiloane and Nosipho Lavuta, ext.2, Lakeside, Johannesburg (2007). Photo courtesy of the artist.

Camille Morineau, director of La Monnaie de Paris, came up with the idea to stage a Womanhouse sequel back in 2015. “She was thinking about this idea of gender and architecture,” Zahra told artnet News. “There had been a lack of contemporary exhibitions dealing with this idea of women and the domestic in a broader way. There really wasn’t anything that went farther than Womanhouse.”

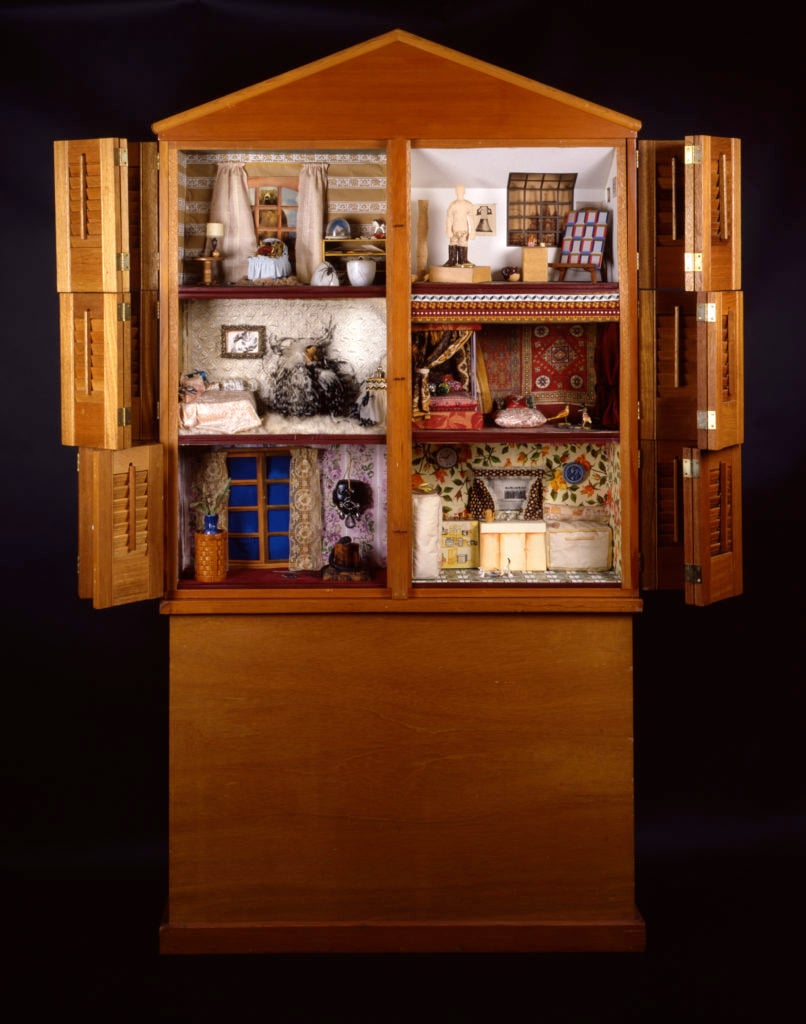

Morineu put together a new show that explores themes about women, but with a broader, more global approach to the ideas that Chicago and Schapiro were grappling with back in the 1970s. The roster of 36 artists from 17 countries includes Mona Hatoum, Zanele Muholi, Sheila Pepe, Martha Rosler, Cindy Sherman, Laurie Simmons, Rachel Whiteread, and Francesca Woodman.

Laurie Simmons, Walking House (1989). Photo courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York.

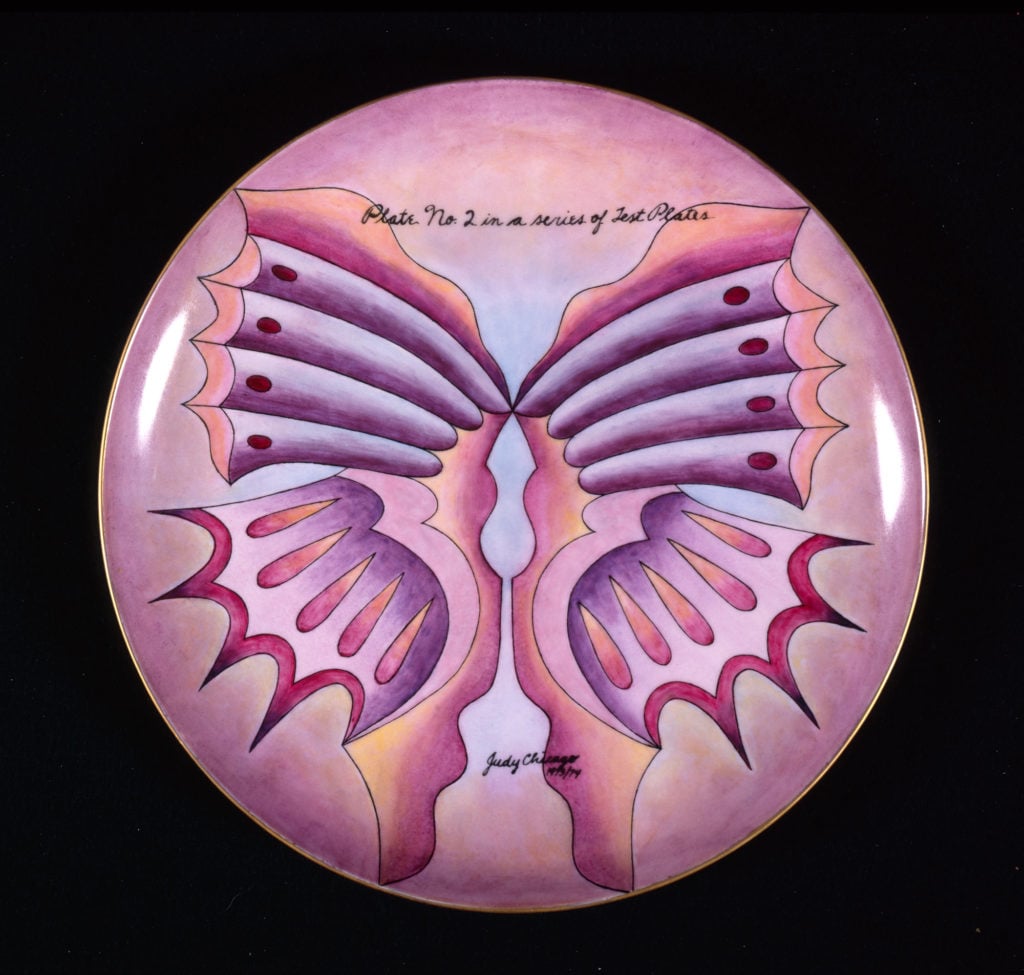

Schapiro’s Dollhouse, which did not appear in the show’s original run in France, is the only work included from the original Womanhouse. The DC iteration of “Women House” also adds a series of butterfly plates that Chicago made before The Dinner Party. None of the other Womanhouse artists are represented.

The original Womanhouse was part of the first year of the Feminist Art Program that Chicago and Schapiro founded at CalArts. “I had watched a lot of young women come up with me through graduate school only to disappear, and I wanted to do something about it,” Chicago said. The program was an outgrowth of a similar one Chicago had run in Fresno the year before, and most of her students came with her to LA. “The program kind of exploded. It was kind of like taking the lid off a boiling pot of water.”

Miriam Schapiro, Dollhouse (1972). Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

“It was the first time a major art school had turned its attention to the needs of female students,” Chicago said. Back when she was coming up as an artist, “the art world was almost singularly inhospitable to women. In order to be accepted at all, even marginally, I had to excise all signs of gender from my work,” she said. “The biggest compliment was to be told that you painted like a man.”

Although her program was popular, Chicago and her students in LA still needed to find a space to convene. They had been meeting at an overcrowded convent when the art historian Paula Harper made the suggestion, “‘Why don’t we do a project about the house?'” Chicago recalled.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #84 (1978). Photo courtesy of Cindy Sherman and Metro Pictures, New York.

The students found a dilapidated mansion that, although run down, suited their needs. “We worked for three months, transforming it and making it ready for installations,” said Chicago, who contributed the in-your-face installation Menstruation Bathroom, a garbage can overflowing with used tampons.

“This was about women reclaiming the domestic space, which a lot of women felt oppressed by because they were pigeonholed as a housewife or mother,” said Zahra. “Womanhouse became a place where they could feel empowered and liberated and make art with creative freedom. It was such a watershed moment for feminist art history in the United States.”

Rachel Whiteread, Modern Chess Set (2005). Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York; Lorcan O’Neill, Rome; and Gagosian Gallery. ©Rachel Whiteread.

Zahra sees NMWA as a particularly fitting venue for “Women House,” which is all about the artists taking back the home, because “the museum’s building was the headquarters for the freemasons, and women were not allowed. Now it’s the only space in the world dedicated to displaying and preserving art by women.”

“As an institution, we have always highlighted gender inequality and the power structures in society—that core idea is really built into our mission,” she added. “Even though this movement is a really potent time to bring these issues to the forefront, NMWA exhibitions have always and will continue to echo important moments of social awareness.”

Judy Chicago, Menstruation Bathroom (1972), part of the original Womanhouse installation. Photo courtesy of the Through the Flower Archives.

For Chicago, it is exciting to see feminism once again at the forefront of social discourse. But she also finds it frustrating that artists are only now “discovering” the very same issues she’s been talking about for decades. “I never engaged in the fantasy that we live in a post-feminist world. I thought that was bullshit,” she said. “Even though there have been very significant changes, there have not been nearly enough—especially at an institutional level.”

Zahra agrees: “We could have a Womanhouse 3.0 in 30 or 40 years.”

Laurie Simmons, Woman Opening Refrigerator/Milk in the Middle (1978). Photo courtesy of of the artist and Salon 94, New York.

“Women House” is on view at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, 1250 New York Ave NW, Washington, DC, March 9–May 28.