On View

Why Zoe Leonard Is the Artist We Need in Today’s Instagram-Addled Age

Leonard's work, now the subject of a Whitney survey, forces us to actually stop and pay attention to what we are looking at.

Leonard's work, now the subject of a Whitney survey, forces us to actually stop and pay attention to what we are looking at.

Taylor Dafoe

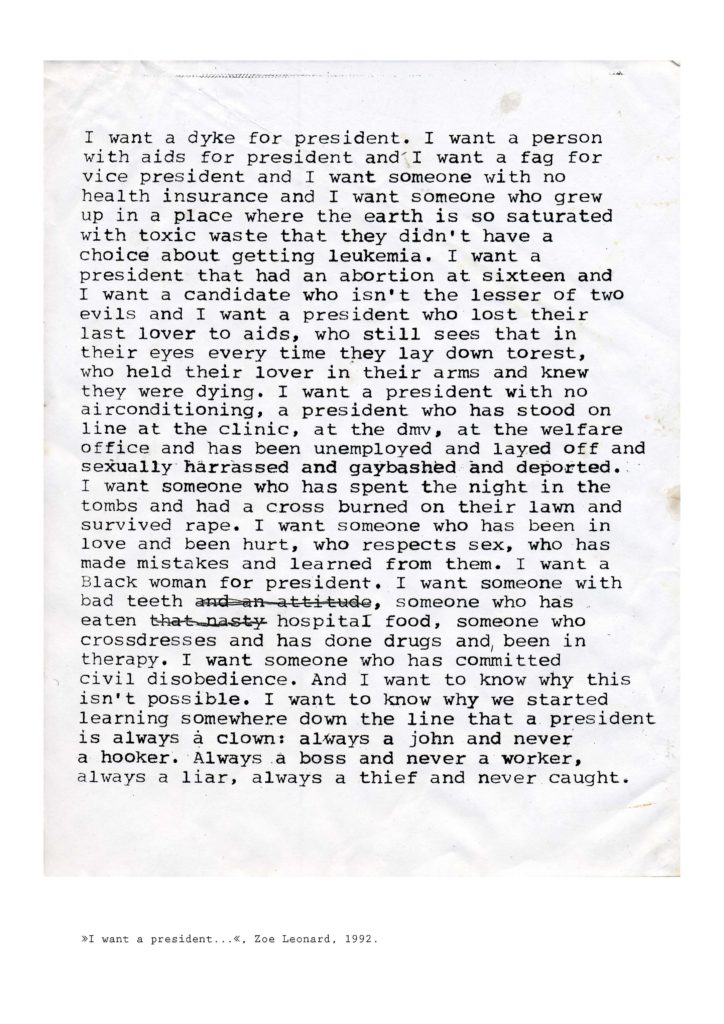

A few weeks before the 2016 presidential election, Zoe Leonard’s prose poem “I want a president” blew up online. You’ve probably seen it. It begins: “I want a dyke for president. I want a person with aids for president and I want a fag for vice president and I want someone with no health insurance…”

The manifesto was shared and re-shared by thousands on Instagram and Twitter, performed by celebrities, and eventually installed on New York’s High Line, where it became the backdrop for political demonstrations and speeches. It was a rare instance of the art world crossing over into mainstream cultural conversation.

For those familiar with Leonard’s work, however, the whole thing was also deeply ironic. For one, the poem was written nearly a quarter-century ago in the midst of the AIDS crisis for a low-budget zine that was never even published. For another, Leonard—a photographer, sculptor, and installation artist—is not exactly custom-made to go viral. In fact, that her prose poem was shared by people who may not have even looked at it carefully stands in opposition to everything Leonard’s work is about. Her art is designed to make us slow down and actually think about what we are looking at, and why.

Indeed, the artist who accidentally went viral is, ironically, also the one who is best equipped to pull us out of our Instagram-addled complacency. In an era of endless distraction, Leonard’s work demands that you pay attention. That’s the only way you can reap its rewards.

Zoe Leonard, I want a president (1992). Courtesy of Zoe Leonard.

Visitors to “Zoe Leonard: Survey” at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the first large-scale overview of the artist’s career, will have the opportunity to see for themselves how engrossing—and impossible to capture on Instagram—her work is.

Curated by Bennett Simpson and Rebecca Matalon from the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (where the exhibition will travel this fall), “Survey” examines the entirety of the artist’s output, from the late ’80s to the present. It includes roughly 100 works, from her serial photo projects to her found-object installations like 1961 (2002–ongoing)—an assemblage of old blue suitcases, one for each year the artist’s life, stretching out into the middle of the gallery.

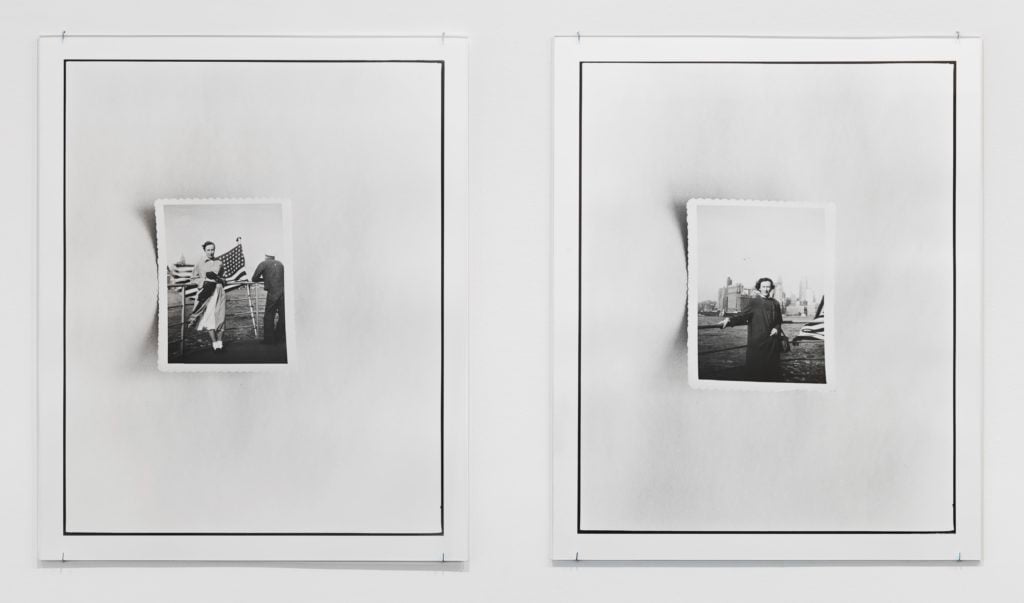

Zoe Leonard New York Harbor I (2016). Collection of the artist; courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, and Hauser & Wirth, New York.

Leonard has a long history with the Whitney. The museum first purchased her work 25 years ago, and she’s been included in three Whitney Biennials—1993, 1997, and, most notably, 2014, when she won the Bucksbaum Award for turning a section of the museum’s fourth-floor gallery into a room-size camera obscura.

Leonard chose not to turn a Whitney gallery into a camera obscura this time around, though she did mount a new site-specific installation. In honor of feminist art historian Linda Nochlin, who died last year at 86, Leonard has printed lines from Nochlin’s seminal 1971 essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” throughout the museum, including in areas only accessible to staff—a reminder to visitors and administrators alike that the art world’s patriarchal structures won’t dismantle themselves.

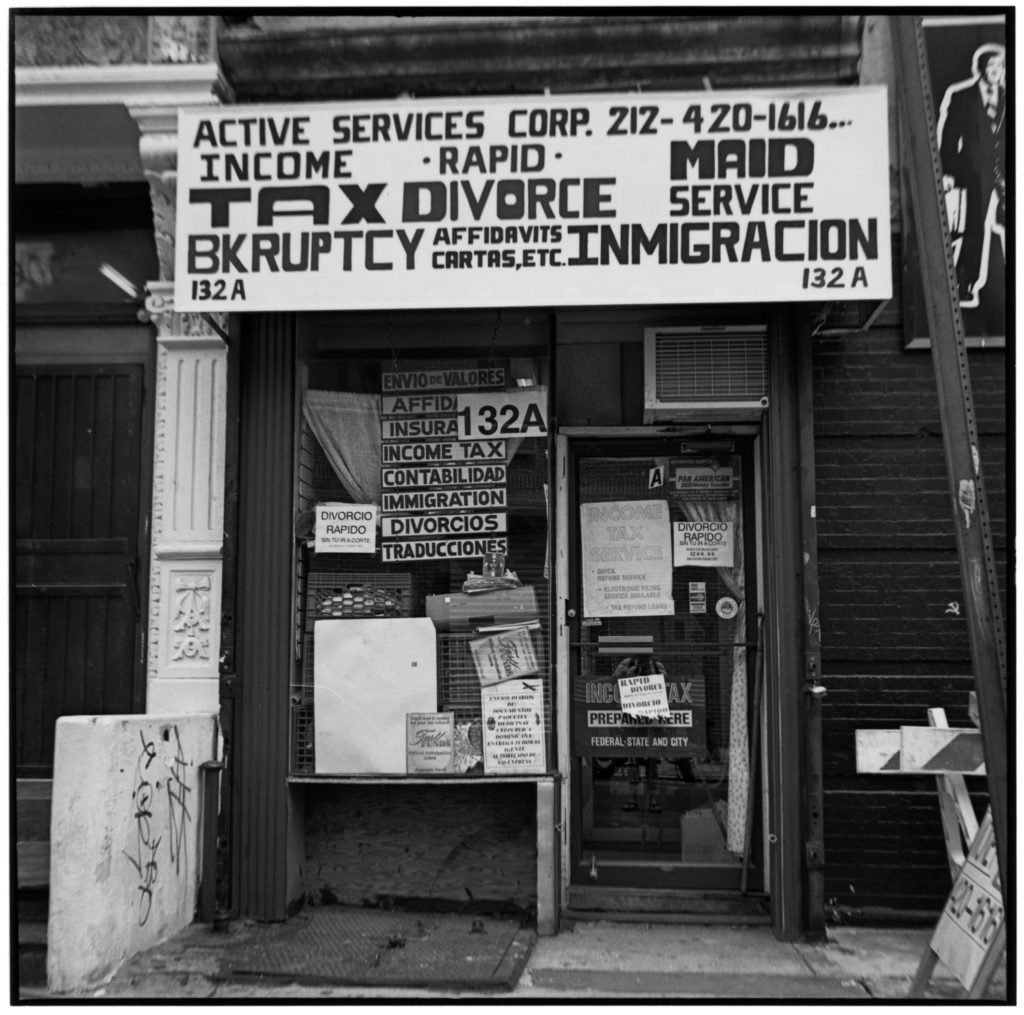

Zoe Leonard, Income Tax, Rapid Divorce (1999). From the artist’s series The Analogue Portfolio (1998–2009). Collection of the artist; courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, and Hauser & Wirth, New York.

“Survey,” the title of the show, has multiple meanings. It is, of course, a survey of Leonard’s three-decade career. But it is also an examination of how Leonard herself interacts with the world, surveying people, stories, and land, literally or figuratively taking a bird’s eye view.

Her aerial photographs from the early ’90s examine the topography of urban and suburban areas. In her landmark series The Analogue Portfolio (1998–2009), she surveys the decline of small, independent businesses through a series of photos depicting shuttered storefronts, derelict signs, and vacant marquees. Each reads like a little memorial to a quirky neighborhood haunt. Viewed in its entirety, however, the installation’s message becomes macro—a symbol of the substantial displacement caused by globalized commerce.

Leonard also has a penchant for collecting artifacts from the past, tracking down groups of objects over the course of several years, if not decades. But she’s not an archivist, per se. She has no interest in preservation. Instead, she’s interested in how time changes the objects and the narratives they contain. As a viewer, these kinds of projects take time to absorb—you, like Leonard, have to look carefully to detect the patterns and changes.

Zoe Leonard, You see I am here after all (2008). Collection of the artist; courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne. Photo: Bill Jacobson, New York.

Take, for instance, her two installations You see I am here after all (2008) and Survey (2009-12), collections of thousands of vintage postcards depicting the same natural wonder, Niagara Falls, in different years and from various vantage points. The postcards show numerous signs of use—corners are curled, imagery is faded, handwritten notes remain. They aren’t archival records of the past so much as a portrait of the ways in which the production of images has evolved over the last century, and how those changes inform our interpretation.

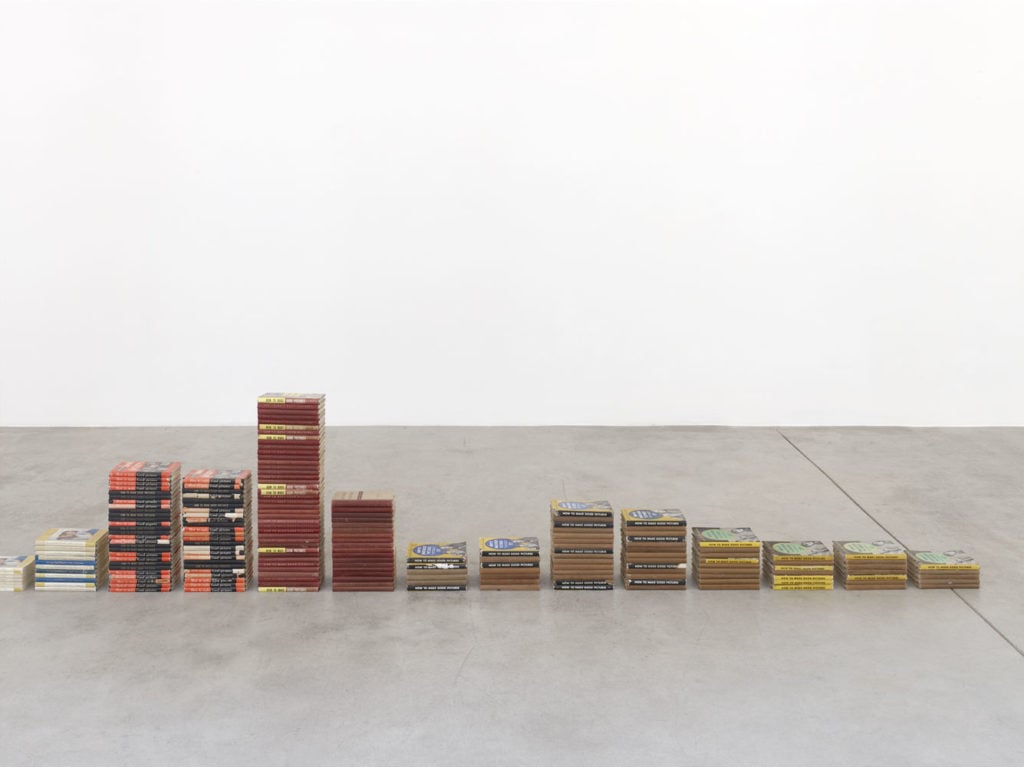

In a newer installation titled How to Take Good Pictures (2018), Leonard has positioned more than 1,000 copies of the eponymous book—a how-to manual published from 1912 to 1998 by Kodak—in successive stacks on the gallery floor, arranged chronologically by edition. Walking from one end of the 20-foot-long installation to the other, a paradox emerges: The covers change many times throughout the book’s print run—a sign of the technological advances in printing techniques—but the ideas that make up the book don’t. With each new edition, the book reiterates the same criteria for “good pictures,” and illustrates those standards with different sets of camera-carrying, well-to-do white people.

Zoe Leonard, How to Make Good Pictures (2016). Courtesy of Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne, and Hauser & Wirth, New York. Photo: Simon Vogel.

Leonard doesn’t seek to redefine the notion of “good pictures,” here or elsewhere in the show. She merely invites us into a room where we can consider that notion ourselves, and reminds us that the act of looking, whether it be in a gallery, on the street, or—especially—on a screen, is never truly a passive one.

“Zoe Leonard: Survey” opens Friday, March 2nd at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and will be on view through June 10th, 2018.